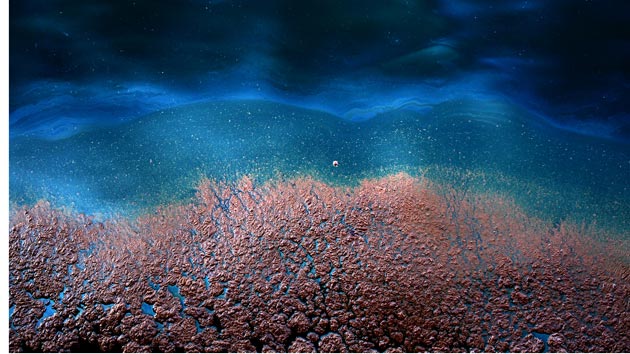

Brandon Kruse/The Palm Beach Post/ZUMA

This story originally appeared on The Huffington Post and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A year after BP’s disastrous 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, a team of researchers found that dolphins in the vicinity of the spill showed major signs of sickness, a new study says.

According to a new peer-reviewed study published Wednesday in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, a team of government, academic and non-governmental researchers identified previously unseen health issues in bottlenose dolphins examined in August 2011 in Louisiana’s Barataria Bay.

Researchers examined 32 dolphins, including 29 that received comprehensive physical and ultrasound examinations. Nearly half of the sampled population were identified as being in “guarded or worse” condition, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Another 17 percent were in poor or grave condition and “not expected to survive.” Among the health problems were lung damage and low levels of adrenal stress-response hormones. A quarter of the dolphins were also underweight.

The researchers said the dolphins’ symptoms resemble those of mammals in laboratory studies of oil exposure. “The decreased cortisol [hormone] response is something fairly unusual but has been reported from experimental studies of mink exposed to fuel oil,” researchers said. “The respiratory issues are also consistent with experimental studies in animals and clinical reports of people exposed to petroleum hydrocarbons.”

“I’ve never seen such a high prevalence of very sick animals–and with unusual conditions such as the adrenal hormone abnormalities,” lead author Dr. Lori Schwacke said in a NOAA press release.

A BP representative challenged the findings in a statement to The Huffington Post. “The symptoms that NOAA has observed in this study have been seen in other dolphin mortality events that have been related to contaminants and conditions found in the northern Gulf, such as PCBs, DDT and pesticides, unusual cold stun events, and toxins from harmful algal blooms,” the representative said. “The symptoms are also consistent with natural diseases such as Morbillivirus and Brucellosis.”

The study’s authors did note that dolphin deaths in Barataria Bay are part of a larger unusual mortality event that has affected the northern Gulf of Mexico region since February 2010 and includes at least 1,050 strandings. One “cannot dismiss the possibility that other pre-existing environmental stressors made this population particularly vulnerable to effects from the oil spill,” the authors wrote.

The study did, however, compare the Louisiana dolphins to others in Florida’s Sarasota Bay, which was not affected by the spill. Researchers tested blubber samples from the Barataria Bay dolphins and found relatively low concentrations of common persistent pesticides, PCBs and other chemicals.

Schwacke and co-author Dr. Teri Rowles told NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration that the levels of tested chemicals in the dolphins’ blubber “were actually lower than the levels in Sarasota Bay dolphins.”

“We don’t think that the health effects we saw can be attributed to these other pollutants that we looked at,” the scientists added. They concluded that the Louisiana dolphins were five times more likely to develop moderate to severe lung disease than their Florida counterparts.

“While we have seen an unusual number of dolphin deaths during and after the spill, this report verifies that the oil took a larger toll on dolphins,” said Jacqueline Savitz, a vice president of the international ocean conservation and advocacy organization Oceana, in an emailed statement. “Oil production in the Gulf has had a much larger toll on the ecosystem than many people realize.”

Along with its declared commitment to Gulf restoration, BP also maintains offshore oil interests in the area. The company announced Wednesday it had made a “significant oil discovery” after drilling a well in approximately 4,900 feet of water about 300 miles from New Orleans.