Get your flu shot. It's altruistic!<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=flu&search_group=#id=63109657&src=3f6297a7216236be68c42223c09739f9-1-52" target="_blank">Helder Almeida</a>/Shutterstock

This year’s flu season is no joke: On Friday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that it had reached epidemic status. Although experts believe that the season may have peaked in most places, flu incidence is still thought to be very high. The media blitz about the flu seems to be an epidemic of its own—so I spoke to several experts to set the record straight on some of the most common flu questions.

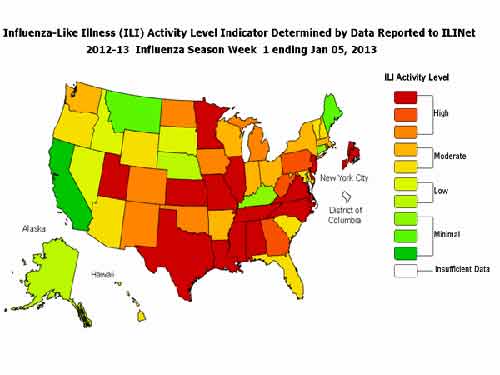

Where in the US is the flu worst right now?

It’s sort of hard to tell, since the CDC is not releasing any real time data; its stats are about a week old. Also, maps like the one below don’t track the flu itself, just flu-like symptoms. Here’s a look at the CDC’s symptom activity map for the week that ended on January 5:

How do I even know I have the flu? How can my doctor tell?

To know for certain, you’d need to have a blood test. But most doctors won’t do that, since it won’t really change the treatment (rest, drink fluids). But there are some key differences between a bad cold and a flu, says CDC spokesman Curtis Allen. “You will be running a high temperature for several days, and it will keep you in bed for a week or more,” he says. But the most distinctive feature of the flu is its sudden onset. “You could be feeling fine at 10 and very sick at noon.”

If the flu season has peaked, should I still get a flu shot?

Yes. A typical flu season is 10 to 12 weeks long—so if it just peaked, that means there’s still another five or six weeks left. The caveat: The shot takes about two weeks to kick in, so even if you got the shot today, you could still come down with the flu, says Allen. Even if you think you’ve already had the flu this year, you should get a shot; it’s possible (though unlikely) that you could still come down with a different strain.

Can you get the flu from the flu shot itself?

No. That’s impossible, since the virus in the shot is not alive. You might get soreness, irritation, or even a fever after the shot, but that’s your body reacting to the shot, not the flu.

If so many people get flu shots, how come there’s still an epidemic?

This year, a little more than a third of the population got one of the 128 million flu shots that were distributed to clinics nationwide. That’s pretty good—but unfortunately the shot is only about 62 percent effective. That’s pretty typical for a flu shot, says Allen.

I’m young and healthy. It’s not like the flu is going to kill me. So why should I bother with the vaccine?

Herd immunity. If you don’t come down with the flu, there’s less of a chance that your elderly neighbor, your friend’s infant, or your coworker who’s going through chemo will.

I tried to get a vaccine, but the damn pharmacy ran out. I give up.

Not so fast! The CDC says that there’s plenty of vaccine this year to go around. There might be shortages at particular clinics, but they’ll be getting more in the next few days. You can check back or try somewhere else.

How do they figure out what to put in those shots, anyway?

You can thank the Southern Hemisphere for this year’s vaccine. During our summer, it’s flu season down under. Public-health experts monitor the strains there and use that information to predict which strains will hit us down the road. This year, they did a pretty good job of figuring out which three strains to include in the vaccines; the CDC estimates that 90 percent of this year’s flu cases are from one of the three strains in the vaccine. Next year, Allen hopes that the vaccine will include four strains.

That said, flu prediction is not an exact science, says Jeffrey Shaman, a flu researcher and assistant professor in the department of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “They monitor the flu, they see what’s happening,” he says. “People look at that and get a feel for the patterns. It’s what we used to do for weather before we had sophisticated models.” Shaman is trying to improve this science with a new tool that uses real-time data from Google Flu Trends, which employs users’ search terms (“flu,” “fever,” “body aches,” etc.) to paint a picture of the location and severity of the flu. (It’s actually pretty accurate.) Since Google’s information is constantly updating, Shaman’s models are continuously learning new information about how the flu behaves—thus increasing their accuracy. Shaman says his model can offer pretty accurate predictions of flu timing and case numbers at the municipal level. He declined, however, to offer a prediction for this year.

Why is there a “season” for the flu?

Several reasons, says Shaman. Some have to do with us humans: In the winter, we spend more time indoors sneezing on each other. During this time of short days and long nights, we don’t get as much vitamin D or melatonin—both thought to be essential for healthy immune system function. Then there’s the virus itself: It seems to thrive when absolute humidity is low, a common condition in cold winter weather.

So that’s why the flu is so bad this year—the drought! So climate change actually made the flu worse, right?

Wouldn’t it be nice if epidemiology were that easy? Unfortunately, it’s not. If that were the case, you’d never see the flu in hot, humid places. But there’s just as much flu in Florida right now as there is in some parts of Canada. Other variables make it impossible to predict flu seasons based on weather alone.

It’s worth noting, though, that in a paper last year, Shaman and his colleagues did document that each of the four flu pandemics of the 20th century were preceded by La Niña cycles, likely because birds mingled with each other differently during these unusual weather patterns. The flu strains that they were carrying probably hybridized and created a strain so new that humans had no immunity to it. Since, as we recently learned from this Climate Desk video, climate change does interact with El Niño/La Niña cycles, it’s not completely out of the question that global warming could affect flu transmission, at least indirectly.

What’s the difference between this year’s seasonal flu and other kinds of flu (like avian and swine)?

They’re just different strains. What allowed 2009’s swine flu—properly called H1N1—to turn into a pandemic was that it was a novel strain. That’s unlikely to happen with this year’s seasonal strains, since they’ve all been around in humans before, so we have some immunity built up. Fun fact: H1N1’s symptoms were actually much milder than this year’s flus.