Photographs by Justin Maxon

[Editor’s Note: See a related photo essay here.]

THE FIRST BABY’S NAME was America. She was born in September 2007, with Down syndrome, two heart murmurs, and part of her upper lip missing. She couldn’t suck from a nipple, so her mother, Magdalena Romero, would stay up through the night to feed her with a special tube. America showed pleasure in music and delighted in being held by her four siblings. Magdalena thinks they felt a special tenderness for her because of her vulnerability.

Hospital officials told Magdalena that the baby wouldn’t live a year, but she didn’t want to believe it. Then, one morning when America was nearly five months old, her lips turned purple. Concluding that paramedics would consider a rescue futile, Magdalena drove the baby to the hospital herself and insisted that all efforts be made to save her. For a few days, America survived, tethered to machines. Then she died in her mother’s arms.

A few flowers struggle to grow in the tiny patch of soil in front of the Romeros’ house in Kettleman City, California, a farmworker community halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Outside, the powder blue trim is peeling; inside, the house looks sparse, unfinished, except for an alcove off the living room that has become a memorial to America. On the wall hangs a carefully embroidered cloth with her name and birth date in red script and her tiny hand- and footprints rendered in pink; rosary beads are draped over the frame. Nearby, three photos of America sit atop a VCR—they’re typical baby pictures, filled with pink and lace, that startle because of America’s missing lip. Magdalena stands in front of the shrine; her lips form a slight smile, but her eyes look uncertain. “You feel all the time, every hour, that something is missing,” she says. Magdalena, now 33, dared to have another child, whom she also named America. The toddler is healthy, but Alondra, her six-year-old sister, keeps asking, “Is this baby going to die too?”

There are between 30 and 64 births each year in Kettleman City. In 15 of the 22 years since California’s public health department began tracking birth defects, all babies in the town were healthy, and in five other years, only one birth defect occurred. But in the last two years and 10 months, residents say, at least 11 babies have been born with serious birth defects. Three eventually died; another was stillborn. Most have cleft lips or palates, and some have other, graver maladies. “When my child was born,” Magdalena says, “I thought she was the only one with a deformity. But when it began happening to other babies, I realized there was something abnormal in my community.”

Maricela Mares-Alatorre, who is related to Maura by marriage, has been battling Kettleman City’s hazardous-waste dump for years; her son Miguel, 15, is part of a youth group called Kids Protecting our Planet.

Maricela Mares-Alatorre, who is related to Maura by marriage, has been battling Kettleman City’s hazardous-waste dump for years; her son Miguel, 15, is part of a youth group called Kids Protecting our Planet.

KETTLEMAN CITY—a dot on the map so insignificant that it is technically not even a town but a “census-designated place”—rose out of the scrublands of the western San Joaquin Valley in the late 1920s, following the discovery of oil in the nearby Kettleman Hills. The second-longest street in town, all half a mile of it, is named General Petroleum Avenue, and the third-longest is Standard Oil Avenue. Those names are as close to wealth as the town gets. Nearly half its 1,500 residents live below the poverty line, according to the 2000 census. A couple of miles south on Highway 41, at the junction with Interstate 5, sits an agglomeration of motels, gas stations, an In-N-Out Burger, and a Starbucks, but the town itself has no pharmacy, high school, or movie theater. It also lacks sidewalks, a supermarket, and a clean drinking-water supply (though the 444-mile California Aqueduct, which conveys water from the Sierras to dozens of Southern California cities, runs just past its border). Most Kettleman families travel 32 miles to Hanford, the county seat, to shop for food and bottled water.

Kettleman City mothers—including Magdalena Romero, left, and Maura Alatorre, center—show photos of their babies to EPA officials.

Kettleman City mothers—including Magdalena Romero, left, and Maura Alatorre, center—show photos of their babies to EPA officials.

Kettleman City does have a few convenience and liquor stores, three well-attended churches (Catholic, evangelical, and Pentecostal), and one tiny restaurant, La Perla, where the most popular menu item is a $3 burrito. Then again, popularity at La Perla is a relative concept; on most days it attracts only five or six patrons. Many families hail from the same Mexican town—La Piedad, in the state of Michoacán. Many have lived in Kettleman City for three generations; others arrived in the last few years. Maricela Mares-Alatorre, a 38-year-old teacher in a GED program for farmworkers, is one of a tiny number of residents with a college degree. She describes Kettleman City as having “a Mayberry feeling with a Latino twist—that’s why I stay. Even if I left, that doesn’t mean the problems get solved. There are still vulnerable people here who can’t speak for themselves, and we’re supposed to abandon them?”

The “problems” are not just the recent wave of birth defects, but the many possible explanations for it, and, most worrisome of all, the prospect that the reason will never be identified. That uncertainty—which no one quite wants to admit—hovers over the town like smog.

Alatorre with her son, Emmanuel, who was born with a cleft lip.

Alatorre with her son, Emmanuel, who was born with a cleft lip.

Despite Kettleman City’s remote setting amid almond groves and tomato fields, its residents are exposed to a startling array of toxic chemicals (PDF). Nearly 100 trucks spewing diesel fumes roll through town daily on Highway 41, and many more come by on Interstate 5. More than half of Kettleman City’s labor force consists of farmworkers who are routinely exposed to toxic pesticides, and residents can smell the chemicals sprayed on the fields that border the town on three sides. Kettleman City’s two municipal wells are contaminated with naturally occurring arsenic and benzene. And there are projects in the works to build a massive natural gas power plant nearby, as well as to deposit 500,000 tons per year of Los Angeles sewage sludge on farmland a few miles from the town.

But the biggest environmental villain, in the view of local residents, is Waste Management Inc., which operates a vast hazardous-waste dump three miles from town. Waste Management is the nation’s largest waste-disposal company, and the Kettleman Hills landfill is the biggest toxic-waste dump west of Alabama, where another Waste Management facility is located in another poor, minority community. California’s two other toxic-waste dumps are also located near Latino farmworker towns.

A wooden cross made by a friend hangs in one of the Romero household’s two shrines to baby America, who died at five months.

A wooden cross made by a friend hangs in one of the Romero household’s two shrines to baby America, who died at five months.

Last year the Kettleman site accepted 356,000 tons of hazardous waste, consisting of tens of thousands of chemical compounds including asbestos, pesticides, caustics, petroleum products, and about 11,000 tons of materials contaminated with PCBs—now-banned chemicals linked to cancer and birth defects. Waste Management has been seeking permission since 2006 to increase the dump’s size by nearly 50 percent.

Kettleman City residents have been fighting that proposal, as they’ve fought other Waste Management projects over the years. In the early 1990s, the town became something of a cause célèbre when it resisted plans to build a toxic-waste incinerator at the dump. (Waste Management ended up withdrawing its application.)

Children at Templo Betel, one of three churches in the town of 1,500.

Children at Templo Betel, one of three churches in the town of 1,500.

Among the organizers in that case was Bradley Angel, a 56-year-old Long Island-reared Greenpeace activist who went on to run a San Francisco-based environmental nonprofit called Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice. Angel continued to follow events in Kettleman, and in 2007, after a battle over Waste Management’s application to continue storing PCBs at Kettleman Hills, he proposed doing a health survey of the town. Greenaction workers and two local environmental groups devised a 36-question survey and started knocking on doors.

What Angel expected to find was an abundance of cancer and asthma, diseases that are found at higher rates in places with substantial air pollution and that are prevalent in Kettleman City. But by the time volunteers had spoken to about 200 residents, they’d learned that five babies born over a 14-month period had cleft palates and other serious birth defects, and three of those babies had died. Since they’d counted only about 25 births during that period, they believed they had uncovered a stunningly large birth-defect cluster. Angel considered the findings so alarming that in 2008 he called off the survey to focus on publicizing the birth defects.

Ivan Rodriguez, 29, with his son, Ivan, who was born with a cleft palate.

Ivan Rodriguez, 29, with his son, Ivan, who was born with a cleft palate.

For many months, he got no traction. Government and Waste Management officials repeatedly dismissed his calls for a state investigation of the birth defects. Dr. Benjamin Hoffman, Waste Management’s chief medical officer, told the Hanford Sentinel in July 2009, “I’ll make a guess that you’ll not find that cluster, that it doesn’t exist…There are some birth defects, but I’m going to bet there’s no unifying cause.” Three months later, Kings County health officer Michael MacLean testified at a county planning commission meeting: “If the United States doesn’t know what causes most birth defects, what do you think is the probability that we’re going to figure this out in [these] cases? We will only find what might possibly have caused this. We’re going to end up with the same thing we started with.”

Farm laborers heading to work in the blueberry fields.

Farm laborers heading to work in the blueberry fields.

The culture clash between Kettleman City’s farmworkers and the white ranchers who hold power in Kings County was on full display at a Board of Supervisors meeting to consider Waste Management’s application in December. About 150 Kettleman City residents rode buses chartered by activist groups to attend the meeting in Hanford. They were greeted by a few dozen police, including a K-9 unit, and a few hundred Waste Management employees dressed in green company T-shirts, who filled the rear third of the auditorium. The Kettleman residents who testified were alternately angry, respectful, dignified, and profane. “We’re people just like you,” said 15-year-old Miguel Alatorre, leader of a youth group that helped conduct the health survey. “We’re not dogs…We’re tired of all this dumping and toxic waste. We want it out.” The supervisors listened impassively.

It wasn’t until the campaign yielded a few newspaper stories that officials started to pay attention. In December, the Board of Supervisors voted for a state investigation into the cluster. But a week later, it also unanimously approved Waste Management’s expansion application. When I asked supervisor Joe Neves whether Kettleman City’s health problems ought to rule out the dump’s expansion, he seemed to view the question as an attack on modernity itself. “Does that mean that we shouldn’t be growing crops?” he asked. “Does that mean we should just let everything go back to nature?”

Oil storage tanks next to the California Aqueduct.

Oil storage tanks next to the California Aqueduct.

In truth, the approval was likely motivated by more practical concerns. Under California law, county governments can tax dumps by as much as 10 percent of their revenue from hazardous waste; Waste Management’s “franchise taxes” to Kings County amounted to more than $1.6 million last year, and the company paid another $380,000 in property tax, making it one of the county’s largest taxpayers. The expansion application still needed signoffs from several other government agencies, but Angel’s threat to tie up the permit in appeals was starting to hint of futility. Meanwhile, Kettleman City residents kept reporting more birth defects; by last spring, Angel was counting 11.

Little Ivan in his Sunday best.

Little Ivan in his Sunday best.

Then the activists got a break. Angel had been lobbying the Obama-appointed regional EPA director, Jared Blumenfeld, and in January Blumenfeld announced his office would review its monitoring of the waste dump. (Blumenfeld also visited Kettleman City and met with the mothers.) Three days later, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger announced that the state Department of Public Health would investigate the birth defects. Soon afterward, an EPA spokesman said the agency wouldn’t approve Waste Management’s application “unless we are confident that the facility does not present a health risk to the community.” California Sens. Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein called for a moratorium on the expansion and sought federal funds for a water-treatment plant that would end the town’s reliance on contaminated well water. At least for the time being, all this has given the people of Kettleman City hope.

THE TROUBLE IS that science is not likely to back them up. To find a chemical culprit for the birth defects would require not just identifying substances in the air, water, or soil that are capable of causing such defects, but also tracing their pathway to townspeople’s bodies. The odds of achieving either are low. For one thing, Kettleman City isn’t big enough to support meaningful epidemiological statistics. Scientists know relatively little about how individual chemicals affect health, and next to nothing about their effects in combination. Kettleman City exists within such a thick chemical soup that it would be hard to identify an individual substance as the culprit—and the precise combination of exposures could be different for each family. Dr. Rick Kreutzer, who heads California’s Division of Environmental and Occupational Disease Control, says that even though the most common defect is a cleft palate, the differences in the other defects indicate that there is no single cause. “We don’t really expect that we’re going to find that one big thing,” he says.

Even more confounding, clusters—of birth defects, cancers, and other health problems—are not necessarily evidence of environmental harm. Richard Jackson, chairman of the environmental health sciences department at the University of California-Los Angeles and a leader in the creation of California’s first birth-defect monitoring program, says “hard-learned experience” has taught him that “clusters are a statistical inevitability…If you throw a bunch of beans on a tile floor, some tiles are going to have five beans, and a bunch of them are going to have none.” Kettleman City’s accumulation of birth defects could be the result of nothing more than chance—though that possibility dwindles with each new case. Heredity, diet, and lifestyle could also play a part.

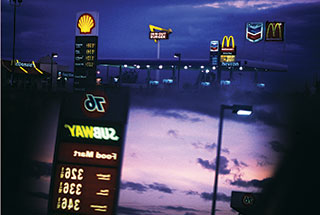

The I-5 Kettleman City exit, about halfway between LA and San Francisco.

The I-5 Kettleman City exit, about halfway between LA and San Francisco.

In the face of all this uncertainty, some scientists are arguing for a new approach to environmentally vulnerable areas called “cumulative impacts.” They maintain that since chemical-by-chemical health studies don’t reflect real-world circumstances, it makes sense to think more broadly, taking into account everything from polluted air and water to poverty, poor health care, and proximity to hazardous facilities.

“We think of biology more as a network now,” says Amy D. Kyle, a University of California-Berkeley public health researcher and cumulative-impacts advocate. “There are lots of things going in your body at the same time, things get turned on and off, they can be interfered with to varying degrees by different chemical stressors. It’s not like a road from A to B—it’s more like traffic. If you have a crash, it doesn’t stop all traffic. The whole system readjusts itself in ways that aren’t linear. [In biology], the outcome depends on what else is going on—how old you are and what your other susceptibilities are, and the likelihood that multiple things can perturb these same pathways is greater than what we thought.”

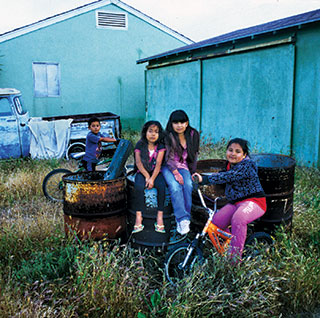

Magdalena Romero’s daughter Alondra, 6 (second from left), with friends.

Magdalena Romero’s daughter Alondra, 6 (second from left), with friends.

What this means for scientists and regulators, Kyle says, is that “we ought to think about more than one environmental factor at a time. That’s different from the current paradigm, [where] policies are addressed at one pollutant at a time. When you get out into communities and you look around, and you see hazardous wastes, less health care, lead paint in their houses, you can’t really think that that collection of environmental factors and [individual] sensitivities don’t often matter. It’s not really scientifically believable.”

Rachel Morello-Frosch, an environmental health researcher at UC-Berkeley, calls Kettleman City “a poster child for cumulative impacts” because residents’ health is compromised in so many ways. “Waste Management needs to be aware that its operations are adding to an already burdened community,” she says. “The facility can’t just pretend it’s operating in a vacuum.”

Tanks outside town hold the oil extracted in the Kettleman Hills.

Tanks outside town hold the oil extracted in the Kettleman Hills.

In the absence of a cumulative-impacts analysis—something that has yet to be attempted by any regulator anywhere in the US—Kettleman City is now the subject of a state-run epidemiological investigation (PDF), almost certainly a bittersweet accomplishment. The likeliest outcome—continued uncertainty about the birth defects’ cause—could in fact help Waste Management by reinforcing its contention that no harm from the dump has been shown.

Jackson concedes that in Kettleman City, where “there’s no way the public will be satisfied without a serious investigation,” an epidemiological study is required—but that doesn’t mean it will have any meaningful impact. “Communities are often led to believe that a scientific investigation will lead to some answers,” Jackson says. “But my own experience is that oftentimes an enormous amount of resources is put into an investigation, and at the end of it we really don’t know much more than we did at the beginning, except that we now know the residents have terrible medical care, terrible dental care, the kids are way behind in school, they’re way behind in immunizations and nutrition.” In some ways, he argues, spending money “to give them an epidemiological study rather than care is really not the right thing to do.”

Because their tap water contains arsenic and benzene, most families rely on bottled water.

Because their tap water contains arsenic and benzene, most families rely on bottled water.

Yet even if the study does not identify a culprit, the attention on Kettleman City still may yield benefits, such as the increasing likelihood that the federal government will fund a water-treatment plant for the town. And the federal investigation of the Waste Management dump may yet lead to tighter monitoring of the facility; this spring, the probe turned up violations (PDF) in handling PCBs. In response to the revelations, Waste Management issued a press release asserting that the chemicals were at “very low levels” and that “the health and safety of Kettleman City residents…are our highest priority.” (The company says the contamination has since been cleaned up.)

But try telling that to 26-year-old Maura Alatorre, whose second child, Emmanuel, was born in May 2008 with numerous problems, including a cleft lip and an enlarged head. Surgery corrected some of the problems, but he continues to have allergies so severe that his doctor prescribed medication usually reserved for older children. He’s had a seizure, and his parents have been told to expect many more because of his most serious problem, a defect in his corpus callosum—a vital portion of the brain that orchestrates communication between its two hemispheres. Emmanuel’s right side lags behind his left, and he is likely to face intellectual deficiencies as he grows. Despite all this, he looks lively and curious and has clearly overcome some of his maladies. “God has made a miracle of my child,” Maura says, sitting on her living room sofa with a smiling Emmanuel on her lap, “but I don’t want to take the risk of having another one.”