Ed Kashi/VII/PowerHouse Books

On August 3, 2011 the British-Dutch oil giant Shell accepted responsibility for two massive oil spills in Nigeria’s Niger River Delta. The spills released an amount of oil equal to 20 percent of what leaked into the Gulf of Mexico after the Deepwater Horizon/BP disaster last year, and many of the area’s fishermen lost their livelihoods. Shell will pay compensation totaling at least £250 million ($410.5 million) to around 69,000 Nigerians—mostly members of the Bodo community—who were affected by the spills. The news of the payout sent Shell’s stock price tumbling, but it should also serve to draw attention to the “scramble for African oil”—a gold rush Ed Kashi and Michael Watts documented in their recent book, Curse of the Black Gold. Today, Mother Jones is republishing some of the photos and text from Curse of the Black Gold.

Nigeria, a major supplier of oil for the US, is the sixth largest producer of oil in the world. Set against a backdrop of what has been called the scramble for African oil, Curse of the Black Gold is the first book to document the consequences of a half-century of oil exploration and production in one of the world’s foremost centers of biodiversity. This book exposes the reality of oil’s impact and the absence of sustainable development in its wake, providing a compelling pictorial history of one of the world’s great deltaic areas.

The publication of Curse of the Black Gold occurs at a moment of worldwide concern over dependency on petroleum, dubbed by New York Times journalist Thomas Friedman as “the resource curse.” Much has been written about the drama of the search for oil—Daniel Yergin’s The Prize and Ryszard Kapuscinski’s Shah of Shahs are two of the most widely lauded—but there has been no serious examination of the relations between oil, environment, and community in a particular oil-producing region. Curse of the Black Gold is a landmark work of historic significance.

(A selection of images and text from the recent book by Ed Kashi and Michael Watts.)

Tanker drivers wait for work in the Tank Park of PTD (Petroleum Tanker Drivers) in Warri. Due to the crisis in the Niger Delta, the refinery in Warri has been shut down for production. Many of these drivers have been waiting for three months at this park to get oil products to deliver around Nigeria.

Workers subcontracted by Shell Petroleum Development Company clean up an oil spill from an abandoned well in Oloibiri, Niger Delta.

Children play in the polluted waters off Bonny Island where the Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas plant is located. NLNG’s plant is one of the largest of its kind in the world. The fishing community of Finima was relocated to make room for this facility, and many residents of the island now live in its shadow in shantytowns.

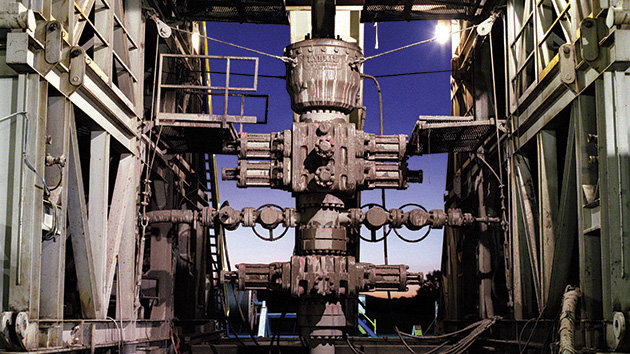

A disgruntled worker tried to board the oil rig “Auntie Julie the Martyr,” run by Nigerian company Conoil. There have been numberous attempts by locals to take over oil rigs as a form of protest.

Owned by Total of France, the Amenam Kpono oil platform emerges from the Atlantic Ocean off the Niger Delta coast.

Aerial view of a Total gas drilling instillation in Rivers State.

Oil-soaked workers take a break from cleaning up a spill in the swamps near Oloibiri.

Three locals sit in a boat in front of a Nembe fishing village in Bayelsa state. With a Shell pipeline running through its little harbor, small fishing enclaves such as this one have seen their waters poluted and fish stocks depleted.

Students in the run-down primary school of Ogulagha take their exams or “just hang out.” Most of the classrooms do not have tables for the students, and most of the teachers do not show up due to lack of pay.

The carcasses of freshly killed goats are roasted by the flames of burning tires at Trans Amadi.

Oil pipelines create a walkway for this young woman through the village of Okrika Town.

Militants with MEND (Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta) brandish their weapons in the creeks of the Niger Delta. Here they check a former Nigerian Army floating barracks that they had destroyed in March 2006. Fourteen soldiers died in that attack, and due to acts like this by MEND, 25 percent of Nigeria’s oil output has been deferred.