Jovaan Lumpkin entered the Connecticut state prison system in 2004, at age 17. In the eyes of his mother, Diane Lewis, he was still her goofy, skinny teenager.

She loved him and had always made sure he had the right clothes: Polo Ralph Lauren, the latest jeans. Her biggest fear was for her son’s safety in prison. But she worried about smaller things, too. Without anyone to braid his hair, she wondered, would he need to cut his cornrows off?

Lewis gave birth to Jovaan at 21 and raised him on her own in Hartford, a once-prosperous city that had gained a reputation for crime and municipal neglect. She later took in three of his younger cousins, whom she treated as her own.

Lewis worked various jobs to support them, including positions at a social services nonprofit and an insurance company. Neither paid a lot, and the family had its financial ups and downs—but Lewis always provided her kids structure and a stable home. She was a no-nonsense mom who demanded to know where Jovaan was at all times, though he didn’t always comply. That protective impulse didn’t change after he was convicted of conspiracy to commit first-degree assault. Lewis made Jovaan promise he would call her every day from prison. “I didn’t want him to come home a stranger,” she said.

Jovaan kept his word. On calls, Lewis would bring him up to date on family news: who’d had a new baby, who had died. He told her about people she knew from back in the day who he’d come across in prison. He’d ask if the new Jay-Z album had come out yet. They ended every call with “I love you.”

All these calls cost a lot of money. The rate varied, but it averaged about $4 for every 15 minutes in Connecticut during Jovaan’s incarceration. They often talked four times a day, the maximum allowed. The charges added up quickly. Every Friday, when Lewis collected her paycheck, the first thing she did was deposit money in Jovaan’s phone account. Many months, she had to pick: the calls or her other bills? “You always choose your kid,” she told me, even if it meant an empty stomach or talking to her son in the dark because her power was shut off.

Over the 11 years Jovaan served time, Lewis spent tens of thousands of dollars on calls to the prison. “We don’t stop being moms or parents, no matter where your kid is,” she said. “You don’t get to pick and choose if you’re a parent or not. I don’t love my kid less in prison.” To her, the calls were nonnegotiable.

Lewis’ situation wasn’t unusual. A pre-pandemic report estimates that one-third of American families with loved ones in prison go into debt to pay for phone calls, and 87 percent of the costs are borne by women. Because incarceration rates correlate with low household income, the fees disproportionately target the poor and keep struggling families entrenched in poverty. Until Lewis met Bianca Tylek, she had never considered that things could be any different.

In May 2019, Lewis, who had been volunteering with the political advocacy group Voices of Women of Color, visited the state Capitol for its annual Hartford Day celebration. She knew just about every community advocate, activist, and lawmaker in the crowd, and was chatting with a friend when Tylek, a criminal justice reformer, spotted her “People Over Prisons” T-shirt and came over to introduce herself. Tylek told Lewis she was working on a campaign to make prison phone calls free.

She seemed well intentioned, but Lewis had encountered plenty of ineffective nonprofit workers before. “Bless her heart. She is so cute,” Lewis thought as they talked. “But baby, phone calls ain’t gonna be free in Connecticut because—are you kidding?—Black and brown families are affected.” (Black people make up 13 percent of the state population but 44 percent of its prisoners.) “They ain’t gonna do shit about that,” Lewis told herself.

She was wrong.

However improbable it seemed, Tylek and a small crew of advocates, legislators, and community members would take on a multibillion-dollar company—and win. In 2021, after a lengthy campaign, Connecticut became the first state to let prisoners make free calls, saving their families some $10 million a year. “I will always be in disbelief that it passed,” Lewis said.

In some ways, Connecticut was unique. It’s a small, putatively liberal state with reform-minded politicians who are acutely aware that the state disproportionately imprisons people from just a few communities. Half of the roughly 10,000 people in its prisons come from six cities that together make up less than a fifth of the state population. (Lewis’ neighborhood, Upper Albany, had a 2020 incarceration rate of nearly two adults per 100.) But the campaign also demonstrated the efficacy of a strategy that can be applied to any state. Organizers elsewhere, including California, have taken notice. After the win in Connecticut, a question unthinkable just 10 years ago has become worth asking: Is this the end of prison phone fees for families?

Jovaan Lumpkin with his mother, Diane Lewis.

Courtesy Diane Lewis

Phone calls are among the most important services that prisons offer. On a practical level, they are needed to arrange housing and work before people reenter society. But more vitally, they provide a connection to life outside. “The three things you have in prison are calls, commissary, and visits,” Jovaan told me. The calls with his mother gave him an emotional ballast. Throughout his time in prison, she also visited him in person once or twice a week—shouldering additional costs for gas, child care, and time off—and Jovaan occasionally wrote letters. But the daily talks were the bedrock of their relationship. When there’s no money in your phone account, he told me, “you have no idea what is going on.” The world beyond the prison walls feels remote.

Studies show that incarcerated people who maintain strong social connections through calls and visits with friends and family are less likely to reoffend. In 2008, Florida State University researchers reported that the chance of reconviction within two years of release shrank by about 4 percent for each visit a person received; an exhaustive 2011 study from Minnesota’s corrections department found that visited inmates had a 13 percent lower recidivism rate. Such stats are resonant in places like Connecticut, where the revolving prison door has been an acute problem. According to the state’s most recent analysis, in 2012, nearly four out of five released prisoners were rearrested within five years.

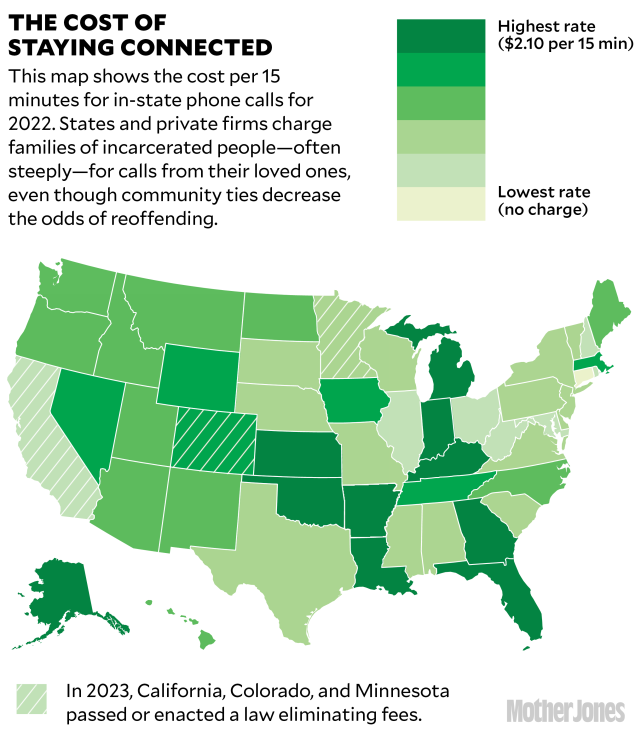

Charges for prison calls differ from state to state. In 2019, the year Jovaan got out of prison, a call ranged from 14 cents per 15 minutes in Illinois to $4.80 per 15 minutes in Arkansas. During Jovaan’s time inside, Connecticut was one of the most expensive states for incarcerated people to talk on the phone: His mother paid between $3 and $5 per 15 minutes. Landline calls—a 150-year-old technology—are now practically free outside of prison, and collect calls barely exist anymore. So, why the ridiculous rates?

The main reason is that a handful of well-connected firms dominate prison telecommunications and have little incentive to compete on quality and cost. The telecom providers charge prisoners’ families directly, and then hand over a cut of their spoils to the state. Securus’ contract gave Connecticut up to 68 percent of the fees it took from people like Diane Lewis. Prison calls, in other words, are not a state service partially funded by loved ones, but rather a profit source for states and private companies. Higher state commissions contribute to higher costs for families.

As a result, phone contracts with corrections departments are immensely lucrative. In 2020, Securus, which serves approximately 3,500 correctional facilities, brought in hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue. (Records from Aventiv—a parent company that includes additional prison-tech services—show 2020 revenue exceeding $750 million.) This private administration of public services is part of a larger trend that has quietly transformed almost every facet of the carceral system over the past three decades, from prison architecture to the beds incarcerated people sleep on to the health care they receive.

Still, phone calls are distinctive—“arguably the worst price-gouging that people behind bars and their loved ones face,” as the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative once put it. That’s in part because just a few companies compete for contracts. By the 2000s, big telecoms like AT&T had mostly stopped servicing correctional facilities. Smaller firms moved in, and those companies were in turn gobbled up by private equity firms. Some 70 percent of US prison telecommunications now go through just two companies: Securus and ViaPath (formerly GTL). There has been a lot of scrutiny of private prisons and the perverted financial incentives of the companies that operate them, but the universe of private contractors servicing public prisons is vast, hiding similar dynamics behind the guise of a neutral, state-run system.

When she approached Diane Lewis in 2019, Tylek had been working on criminal justice reform for just three years, but she’d already secured a big win. Her nonprofit, Worth Rises, had helped pioneer a set of strategies that were remarkably effective, helping to persuade New York City to abolish calling fees for its jails. She would later do the same in Miami, San Francisco, San Diego, and Louisville, Kentucky. As the women talked more, Lewis put aside her skepticism and joined the campaign, helping with fundraising and promotion.

Lewis found Tylek disarmingly honest, with a knack for charming her opponents—the kind of person who can chew out a corrections official twice her age and twice her size and then laugh with the guy a minute later. But Lewis also noticed that Tylek’s methods were unusual. Most organizers used a combination of legislative work, media outreach, research, and community organizing. They talked with affected families, fought for legislation, issued reports, and raised public awareness. Worth Rises did all of that, but it was also laser-focused on the money: the multibillion-dollar network of private businesses that feed on the carceral system. Tylek, who has a background in finance, had come to recognize how social problems created by profit-seeking can sometimes be unmade by targeting the people bankrolling such endeavors. Few organizers truly understood the role of private interests, she realized. The goal of her new nonprofit would be to strike at the prison system’s financial heart.

Tylek is short, with a nasally New Jersey drawl and the restless energy of a kickboxer. Her parents, immigrants from Poland and Ecuador, observed her sense of righteous anger from an early age. She grew up near Montclair, a tony suburb, and though her parents were middle class, she went to a private high school, surrounded by wealthy classmates. In high school, she saw how the criminal justice system could cause damage. She dated a formerly incarcerated man and was bothered by the stigma and how he internalized it. She also witnessed the arrests of friends. When they were Black, they got court summonses; when they weren’t, they got sent home.

Tylek attended Columbia University and then took a job at Morgan Stanley, marketing mutual funds to institutional clients, including pension funds. She later joined the investment team at Citigroup, and learned the process by which a private equity firm acquires a multimillion-dollar business like Securus: how deals are financed, how the debt is structured, and the potential risks.

She excelled at the work, but after four years she left Wall Street. With the inequities of the criminal justice system still nagging at her, she headed for Harvard Law. When Tylek graduated, she was surprised to discover that many of the nonprofits fighting the carceral system had little understanding of its economic structure. She decided she would fight for reform through not only legislation, but finance. “People did not understand the extent of the private sector’s involvement in the prison system,” she told me. But Tylek did.

In 2017, she founded the project that would culminate in the launch of Worth Rises. Her target, prison telecommunications, was strategic, chosen for its position at the nexus of problems created by the privatization of prisons: high prices, corporate consolidation, a commission payment structure, and the immiseration of financially stressed families. She researched which firms ran prison telecoms, who financed them, and how each was run.

In November 2017, the private equity firm Platinum Equity acquired Securus for $1.6 billion. As a former financial analyst, Tylek could see weaknesses and organizational patterns other activists might miss in such a move. She understood the shadowy support beams to target. She knew the laws that enabled these businesses to exist, the markets for their debt, the deadlines for their funding, and the composition of their investors.

The following June, Securus sought approval from the Federal Communications Commission to buy a rival, Inmate Calling Solutions. Securus controlled 26 percent of the prison telecom market at the time, and ICS held 6 percent. Such deals seldom generate much notice outside of obscure Wall Street analyst reports. But Tylek flagged it for the FCC and argued that greenlighting the consolidation would be disastrous.

The FCC was well aware of the issue. A long line of advocates had pushed for limits on industry price-gouging. In 2015, under its chair Tom Wheeler, an Obama appointee, the agency had approved a bipartisan effort to tackle the problem. The Trump administration killed it two years later, but FCC staff were receptive to Tylek’s argument and in 2019, Securus and ICS withdrew the merger after staff recommended that then-Chair Ajit Pai deny the transaction.

Her finance acumen paid other dividends, too. As the FCC considered the merger, she was part of a group of activists who reached out to Platinum Equity to talk about the deal. Tylek stood out on the call, recalled Mark Barnhill, a partner at Platinum. She spoke his language.

After the acquisition imploded, Tylek and Barnhill continued to talk, finding mutual grounds for reform. Ultimately, Tylek got Platinum to agree to two things: Securus would refrain from lobbying against efforts to make prison calls free for families, and Platinum would make no further investments in the prison sector. The lobbying part made sense. If calls were free to inmates and their families, Securus would still get paid by the state. That’s how Tylek had pushed the legislation in New York City—by convincing the city to bear the cost. Besides, Barnhill told me, Platinum bought Securus with the intention of changing it for the better.

In 2019, Tylek helped to craft a bill in Connecticut that would allow prisoners to call their families at no cost. She enlisted the help of Josh Elliott, a state lawmaker with whom she’d been making inroads for months. Elliott was cautious at first. He wondered if the bill should be softened to reducing, rather than eliminating, the cost of calls—a strategy other advocates had suggested. But Tylek was adamant: Lawmakers had to think bigger. As Lewis put it to me, “You can never afford the calls.”

Elliott got the bill through committee, but as Worth Rises organizers made the rounds of lawmakers, they started hearing responses that concerned them. One legislator claimed that if the bill passed, Securus would “rip the phones out of the wall”—shutting off all service—or remove other features. (A Securus representative said the company never actually threatened to shut off phone service.)

Tylek was puzzled. Securus had already made a smooth transfer to free calling in New York City. The pushback also felt at odds with widespread local support for the bill. The editorial board of one of the state’s major newspaper chains was in favor, and there’d been a groundswell of popular support. She felt something was amiss.

Then, one afternoon, Tylek received a message from Jim Baker, an ally at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project in Chicago, which monitors the largely inscrutable movements of PE firms. He told Tylek they’d discovered documents showing that Securus had spent $40,000 on lobbying during the legislative session—which seemed like a potential violation of Platinum’s agreement to require Securus to remain neutral. She called Barnhill in a rage. He told her he wasn’t aware of any lobbying against that measure, noting that Securus would have lobbyists in the field for other reasons. “I have the papers!” she told him. “I called to hear what you’re going to do about it!”

Tylek’s efforts paid off. A week later, Securus sent a letter to legislators and Gov. Ned Lamont to make clear it was not opposed to the bill. “I have never seen anything like that before,” Elliott told me.

Platinum maintains that it was never aware of any lobbying by Securus against the bill, and that the firm released the statement to make its neutrality clear. In any case, the legislation lacked the votes needed to pass. Lamont had not publicly supported the bill, and other government entities suggested they couldn’t afford to lose the commission revenue, or fretted about “budgetary implications”—as though the families of incarcerated people were better equipped to pay than the government was.

Bianca Tylek at her home in Manhattan.

Kholood Eid

Tylek pressed on. Worth Rises had been meeting with the boards of pension funds that were major investors in Platinum Equity, informing them that the company profited off the carceral system and urging them to divest. Labor organizers commonly employ such tactics in “capital strategy” campaigns to put heat on management. Tylek saw a similar utility. When she worked for banks, she’d worked with pension funds and knew their boards were often deciding which funds to trust with huge investments, sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars. If she could get an audience, she could appeal to the board members to stop buying into what she considers unethical industries.

Worth Rises also launched a media campaign that put Securus—and Platinum—in the spotlight. As a result, when Barnhill attended a September 2019 meeting of the investment committee of the Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System, one of the nation’s largest pension funds, to talk about a possible $100 million investment in a Platinum PE fund, he was met with questions about Securus. If the Platinum partners were aware of the cultural shift against mass incarceration, the committee asked, why had they chosen to invest in Securus in the first place? Didn’t this call into question their financial acumen? “I’ve been on this board for about 20 years, and I have never seen the amount of negative press on a firm that I have seen before me today,” noted SERS Chair Dave Fillman. The motion to move forward on the investment was met with dead silence.

Tylek had yet another card to play. When Platinum had bought Securus a couple years earlier, it had issued publicly traded debt, a common private equity practice. That debt was now trading well below its initial value—as low as 48 cents on the dollar—which meant investors, traders, and financial analysts already saw the Securus investment as a bad bet. Tylek didn’t need to pull on the heartstrings of institutional investors; she could just point out that the numbers didn’t look good.

Worth Rises also ratcheted up public pressure to oust Platinum’s multibillionaire chair and CEO Tom Gores, who owns the Detroit Pistons, from the board of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The resulting public shaming by artists, curators, and collectors prompted Gores to resign his seat. Tylek’s group then bought a full-page ad in the New York Times aimed at the NBA’s board of governors: “If Black lives matter, what are you doing about Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores?”

In 2021, after a pandemic pause, Connecticut took up the prison telecom issue again. This time, in addition to stats and data, Tylek deployed personal stories. Worth Rises and its allies lined up more than 100 people, many with loved ones in prison, to speak to lawmakers on Zoom, and arranged prerecorded testimony from 10 incarcerated people. Lewis testified at the hearing and helped recruit others.

Erica Abraham, whose brother had been locked up for 21 years, talked movingly about the difficulty of keeping in touch with him. His granddaughter was born while he was inside. She told him of their grandmother’s passing over the phone, and his own mother’s death. When a Republican representative asked Abraham if they wrote letters, she said, “He writes us and we write back, but a call is so much better.” She continued, “If they’re having a bad day, they can call you and you can try to calm them down.”

It was a marathon 12-hour hearing, and the legislators were moved. “We’ve heard a lot of compelling testimony today, but what will stick with me today is the thought of having to choose between being able to have a dad communicate with his kids and afford heat,” said Democratic Rep. Steven Stafstrom. “I can’t imagine in this country, in this state, that this is a decision that anyone should have to make.”

That June, Gov. Lamont signed into law Senate Bill 972, directing the prison commissioner to provide free phone calls to people in custody—and to make any other communications the system provided, including video calls and emails, free as well. To celebrate, Tylek, Lewis, and everyone else involved gathered at Elliott’s house in Hamden for a pig roast. After two long years of work, the group had grown close. Tylek allowed herself to relax in what she describes as a heartwarming moment. “I kept thinking about all the time and effort and people involved,” she said.

In July 2022, the month the bill went into effect, call time between inmates and friends and family outside jumped 120 percent compared to the previous month. The first thing Lewis had done when the bill passed was call Jovaan, who’d gotten out a year and a half earlier. When I asked why she’d devoted so much time to a cause she would no longer benefit from personally, it didn’t take Lewis long to reply: She doesn’t know a single person in Hartford without a loved one in prison, she told me. And it wasn’t entirely out of the question that her son, being a young Black man, could wind up incarcerated again at some point.

She’d always tried to make the best of whatever circumstances she was dealt, she said, but passing this bill changed her. Now, Lewis spends every quiet second of the day—whether lying in bed or walking down the street—thinking about how she can help make the criminal justice system just a little more tolerable. Much remains to be done, but the signs have been positive. Tylek’s rest did not last long. After the cookout, she was back at work, planning which states would come next. In January, California—often a bellwether for national trends—became the second state to abolish charges for calls from prison. (Worth Rises played a supporting role.) Colorado and Minnesota soon followed. In early 2023, President Joe Biden signed a bipartisan bill allowing the FCC to impose price caps on prison calls, and nearly a dozen states are now considering following Connecticut’s example and ending the fees altogether.

Lewis paused for a moment to muse on these successes, and then remarked quietly, as if to herself, “Yes, I think change is possible.”

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.