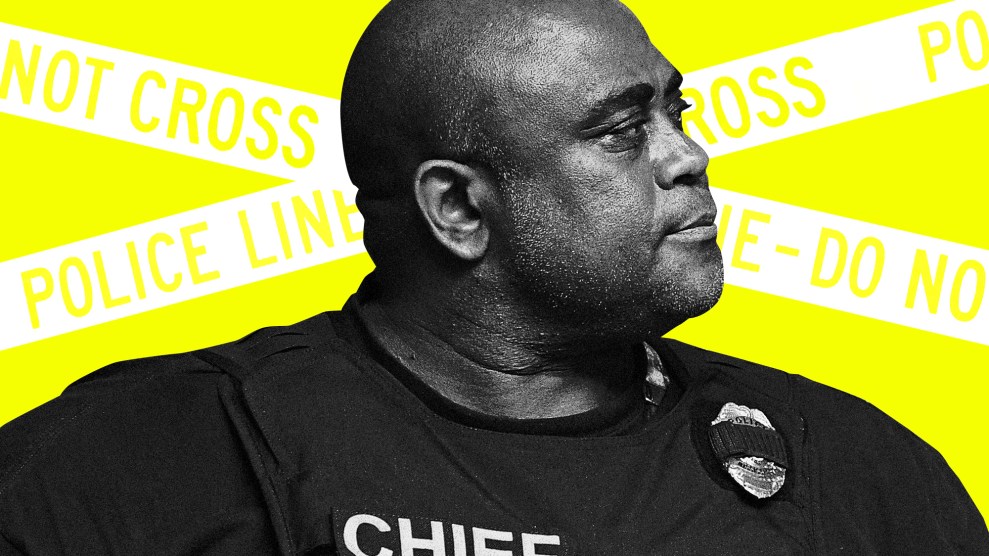

FedEx driver D'Monterrio Gibson at a press conference in FebruaryRogelio V. Solis/AP

Gregory and Brandon Case, a white father and son who allegedly chased and shot at a Black FedEx driver in Brookhaven, Mississippi, have been indicted by a grand jury on charges of attempted murder, in a case that sparked protests because of the defendants’ alleged ties to—and preferential treatment by—local police, who have been accused of minimizing and mishandling incidents of racism.

On January 24, the pair allegedly accosted FedEx driver D’Monterrio Gibson, 24, who had just delivered packages on their street. As Gibson got back in his van, Gregory Case approached in a pickup truck and honked. Gibson began to pull away, thinking he was in the way, but Case swerved the truck into his path.

Gibson nervously steered around the vehicle and continued down the block, where he saw Brandon Case in the middle of the road, holding a gun and waving at him to stop. Gibson shook his head and drove around him, ducking behind the steering wheel. He heard at least five gunshots, as bullets flew through the side of the van and into some of the packages. The pair used the truck to chase Gibson out of Brookhaven and to the interstate.

Gibson wondered whether his race motivated the attack. When he called police after the shooting, a dispatcher told him that someone had reported a “suspicious person” at the address where he’d delivered his packages. “Did you do anything to make them think you were suspicious?” a cop asked Gibson when he filed a report the next day. Gibson said no—that he was wearing a FedEx uniform and doing his job.

Though Gibson presented law enforcement with evidence, including the bullet holes through his van, the Cases weren’t arrested until they turned themselves in six days later. Gibson tried and failed to convince local prosecutors to charge the men with attempted murder; instead, Brandon Case was charged with aggravated assault, and Gregory Case with conspiracy to commit assault.

The grand jury indicted both men for attempted murder anyway, a decision that Gibson described as a victory. But he still worries that law enforcement hasn’t taken the investigation seriously. The Cases, according to a lawsuit, have important connections in Brookhaven: They are allegedly related to former assistant police chief Chris Case, who retired several months after the shooting. The police department denied any relation between the men and said the former assistant chief was never involved with the investigation. But Gibson’s attorney, Carlos Moore, says other Brookhaven residents still believe there’s a family connection and remain concerned about bias. The police, Moore told reporters, are “too close to the kitchen.”

“Most of the Cases are related,” Nicole Beard Steele, a health care worker who previously lived near Gregory and Brandon Case, told me. “I believe if it were anyone else, the cops would be knocking down doors, but instead they were allowed time to turn themselves in. They get special treatment because of who they are.”

A recording of Brookhaven Police Chief Kenneth Collins has heightened those concerns.

Leaked online in November by Mississippi-based activist Marquell Bridges, the audio captures a private conversation that the chief had in the days after the shooting. It suggests that he knew the Cases had a history of gun violence—and that even so, the police held off arresting them until they eventually turned themselves in. Gibson said at the time that the delay could have allowed the pair to hide evidence like the gun, which was reportedly never recovered.

In the recording, Collins says that before the incident with Gibson, the Cases attacked other people on the same road, Junior Trail, where Gibson delivered his packages. “They think they own the whole street,” Collins said of the Cases, mentioning white residents who were allegedly harassed or assaulted by them, including Steele’s family.

“Ask Jammie Steele and them,” the chief says, referring to Steele’s husband. “They [the Cases] ran their asses off of Junior Trail…Pulling guns and shooting these cars down there.”

Collins also named Shelley Harrigill, a former Brookhaven alderman: “She got her ass confronted down there, her white ass,” he says. “The Cases think they own Junior Trail.”

Harrigill did not respond to a request for comment. Nicole Beard Steele also accused Brandon Case of shooting at a female acquaintance and repeatedly threatening to shoot and kill Steele’s daughter. “Brandon thinks he can do anything in Brookhaven that he or his family want to because of their last name,” she wrote in a message to me. “Multiple of our family and friends have had a gun drawn on them by Brandon for being too close to the road. They never filed charges because it would have disappeared.”

Bridges, the activist who shared the recording, said law enforcement should have taken the Cases more seriously. “[H]ow can they harass and shoot at multiple people and still be free?” Bridges wrote on Facebook. The Cases were released from jail on bond within hours of turning themselves in, and the police department reportedly sent multiple officers to protect them and their home ahead of grand jury proceedings. “[T]hey are still walking free 10 months later,” Bridges wrote. “Make it make sense.”

Collins did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Neither did attorneys for Gregory and Brandon Case. Because grand jury proceedings are highly secretive, it’s unclear whether the grand jury heard about these prior allegations of violence. Gibson’s attorney, Moore, told me last week that prosecutors never gave him any of the information Collins discussed in the recording. “I’m very much concerned that the local police department has not done an effective job investigating this matter, that they have been dilatory on purpose,” he said. “I believe it amounts to an obstruction of justice.”

Whether or not police were eager to investigate the Cases, Chief Collins clearly objected to the protests that sprang up after the attack on Gibson. According to a lawsuit by his former Brookhaven police colleague Latoya Beacham, Collins ordered the arrest of Black Lives Matter protesters on false charges. In a response on Facebook, Collins refuted the allegations and accused his former colleague of “trying to destroy me and our town.”

But in the same leaked recording, Collins privately described his opposition to the protests: As I reported, he bragged about crashing one of the nonviolent demonstrations and said he’d even considered assaulting its organizer, Bridges. “I thought about fucking him up right then,” Collins said. “I thought about putting my left foot at the right side of his ass.”

Collins, who is Black, also said he doubted that race motivated the attack on Gibson, who has asked federal prosecutors to pursue hate-crime enhancements to the charges. “I don’t see how it’s gonna be a hate crime,” Collins said, “but I thank God it’s not my decision to make.”

The grand jury indicted the Cases on charges of attempted murder, conspiracy, and shooting at a motor vehicle—more serious charges than the local prosecutor requested. “The grand jury has the ability to charge whatever they find probable cause existing,” District Attorney Dee Bates told CNN in February. A trial date has not yet been set.

Gibson’s attorney, Moore, said his client was “elated” by the jury’s decision, after months of feeling “distraught about the delay in receiving justice.” Gibson “came within an inch of losing his life for simply doing his job as a Black man in America,” he said, “and we believe these men need to be held fully accountable in a court of law.”

“The Cases have finally met their match,” he added. “We will not rest until we secure a conviction and complete justice is received.”