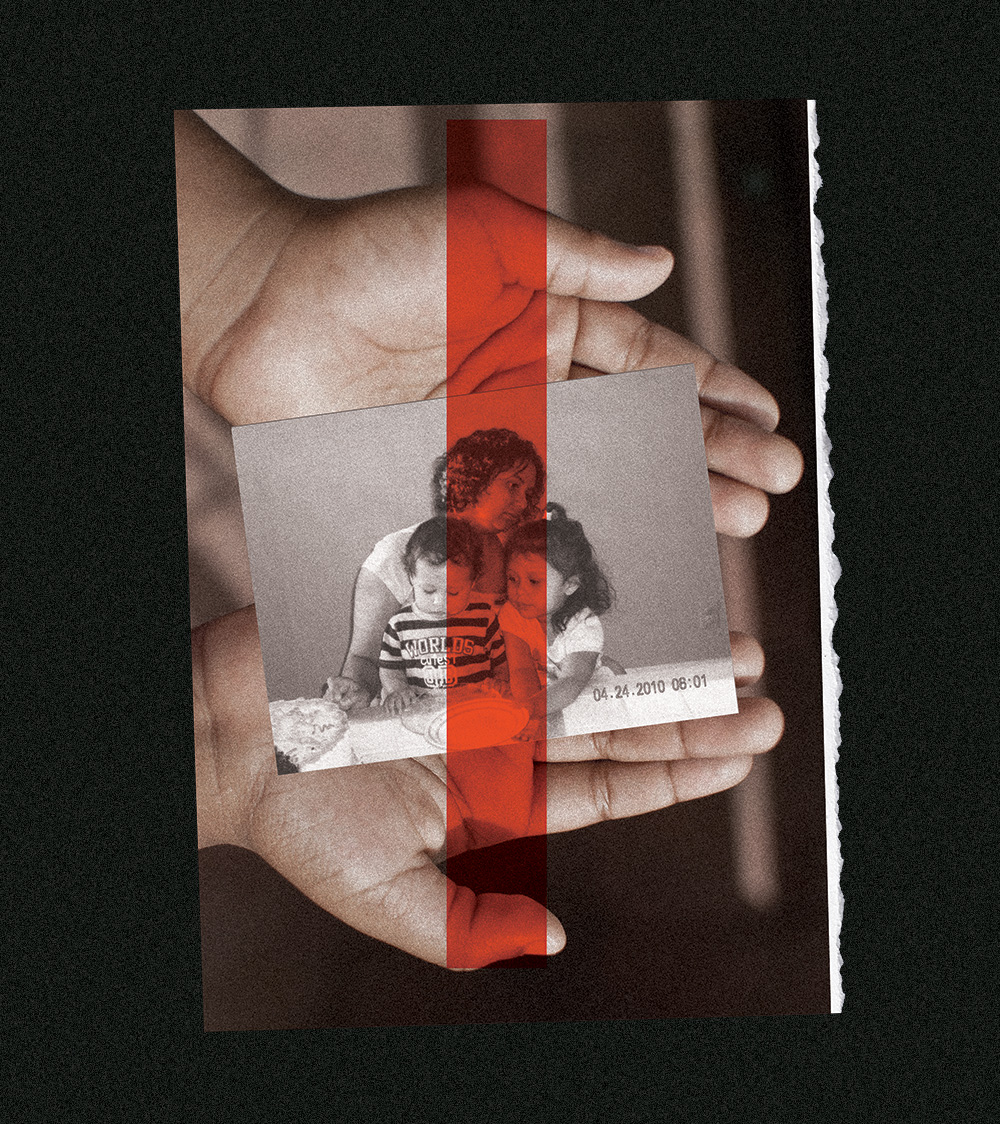

A week before Christmas last year, Kerry King helped three of her children build gingerbread houses in a prison visitation room in Oklahoma. King wanted to make the holiday special for the kids, even under the circumstances. But as the Black 35-year-old spread frosting on a graham cracker while dressed in her orange jumpsuit, her hair braided for the occasion, the mood still felt bittersweet. Since she was incarcerated six years earlier, her kids could only visit once a month, and soon it would be time to say goodbye.

“Do you love me?” Lilah, 10, the most outgoing of King’s children, asked her mother as the visit was ending.

“Of course I do,” King answered.

Lilah thought a moment, her brown eyes serious, and then said something that caught King off guard. “Do you still love him?” she asked. “Because if you still love him, I’ll never forgive you.”

King’s heart dropped. Her ex-boyfriend had abused them both, years ago. He was the reason King was in prison now. But her daughter had never said anything like that to her before. And there wasn’t enough time to have the long conversation they both craved.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Back in her cell, King agonized over whether a letter to Lilah would suffice. She had been mothering her children over letters and phone calls for too long. No matter what, King wanted to tell her daughter, I love you more than I could have loved anyone else, any man. And you should never, ever have to even consider whether I do.

“I am not guilty,” King had said to me over the phone, months before the Christmas visit. “I just wanna go home. I wanna see my kids so bad. It kind of eats you up.”

King has spent countless nights tossing and turning in her cell, replaying the night that pulled her away from her family. (The following descriptions are confirmed in court records and testimony.)

In January 2015, in the small yellow house she shared in Tulsa with her boyfriend and a roommate, King had been bathing Lilah, then 4, when she saw bruises on the girl’s legs and arms. Purdy “was mean,” Lilah said, sitting in the soapy water. John Purdy was King’s boyfriend at the time; he’d recently lost his telemarketing job and sometimes watched Lilah while King worked at a gas station. He’d been physically abusing King for more than a year, often high on heroin, which he’d recently forced her to try. But she had never seen him harm her children. When she asked about the bruises, he claimed Lilah had slipped on the ice.

Two days later, King woke up in the middle of the night and noticed Purdy was not in bed. She was groggy—he had ordered her to shoot up again—but saw a light on in Lilah’s bedroom. When she entered the room, Purdy was holding Lilah’s shoulders, with his fingers wrapped around her little neck. He said they were having a pillow fight, but Lilah whimpered beneath his grasp. “I thought he was hurting her,” King later told detectives. So she tried to free her daughter the only way she knew how, by clenching her fist and punching Purdy in the face. What makes you think you can hit me? she remembers him telling her, turning toward her. He slammed her head against a wall, insisting Lilah needed to be spanked.

King agreed to hold Lilah down like Purdy demanded, hoping that if she complied it would be over faster. But when she saw how hard his blows were, she threw her body over her daughter’s, receiving Purdy’s belt lashes on her own back. Purdy pulled King off Lilah, and King tried to run out of the house to get help from the neighbors or the police—but he blocked her at the door. You ain’t going nowhere, she recalls him saying. “I was scared. I didn’t know what to do,” she later told me, adding that it felt like she “had been in chains.” Purdy dragged King to the master bedroom by her hair and threatened to kill her if she didn’t stay there. He reentered Lilah’s room and locked the door, leaving King outside, listening to her daughter’s cries.

Purdy held King’s phone in his pocket, making it hard for her to call for help. She begged him to come out of Lilah’s room, and then asked him to take a shower with her, anything to distract him. Around 6 a.m., he directed her to lie down in bed. Still high, King reluctantly fell asleep. When she woke up, he wouldn’t let her or her daughter leave the house.

It wasn’t until later that day, when a contractor came to work in the yard, that King’s housemate snuck out and asked the man to call 911. The police found Lilah in a locked room, sobbing. Bruises covered her forehead, cheeks, ears, and neck, and belt lashes cut into her back. Chunks of her curly brown hair were missing.

The police arrested Purdy. King, who had bruises on her own body, helped investigators take her daughter to a hospital. Then she returned home, exhausted. But her nightmare was far from over.

Less than a week later, King was sitting inside in her pajamas when a police car pulled up to her house around 11 a.m. Two white officers asked her to come with them for an interview. “I didn’t want him to hurt my baby,” she told them. “I was trying to prevent this.”

But the officers didn’t buy it. They wanted to know why King waited so long without seeking help for her daughter. Why had she held Lilah down for the beating? Why didn’t she call 911?

They arrested King and put her in jail, where she would stay for more than a year awaiting trial. They accused her of child neglect and permitting child abuse. By the time it was all over, though she had never laid a hand on Lilah, she would be sentenced to 30 years in prison—12 more years than Purdy, the man who had assaulted both her and her daughter.

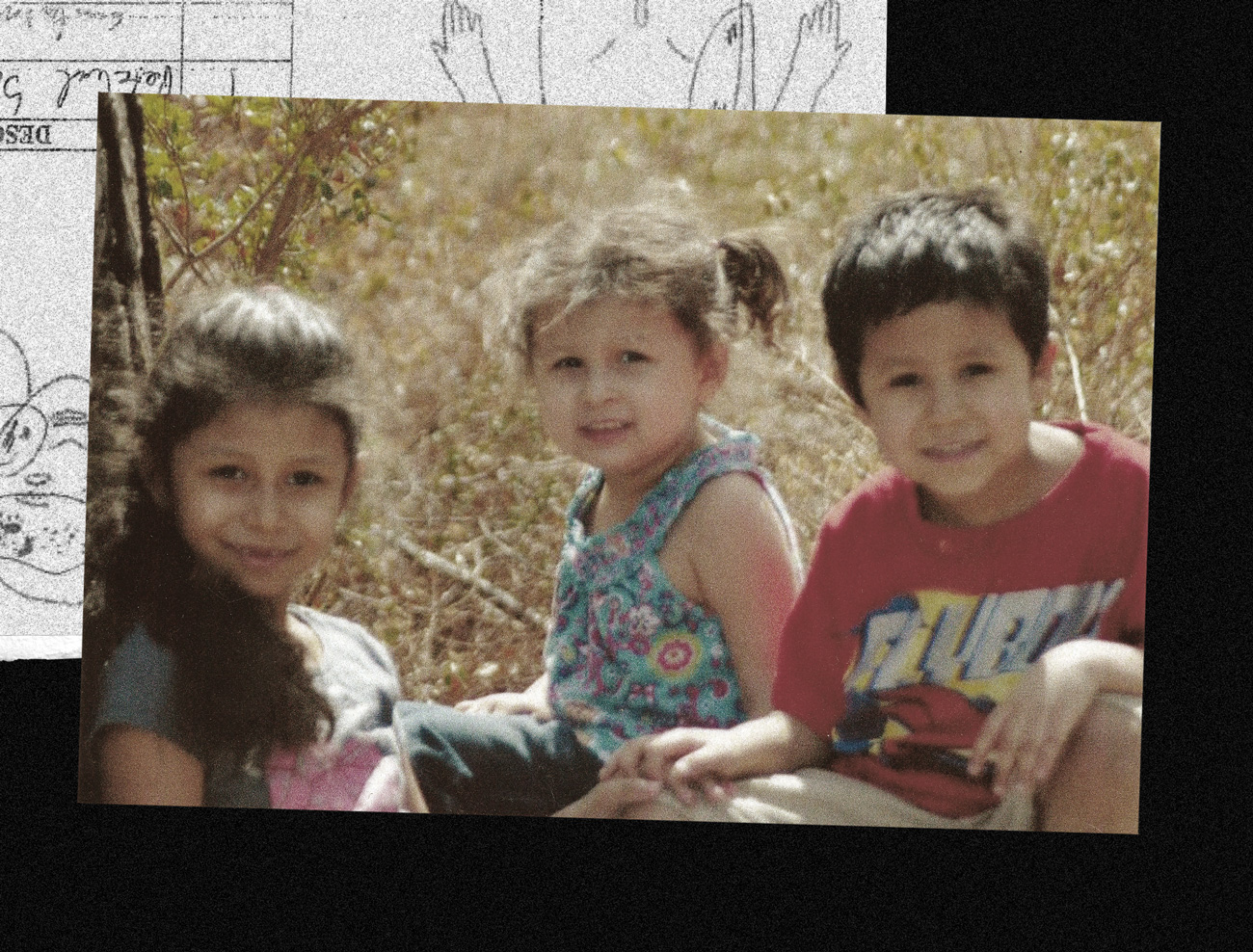

Lilah, seated between her siblings Persia and William, was 4 when King noticed bruises on her legs and arms.

Illustration by Vanessa Saba; Photos courtesy of: Kerry King; Kathleen Araujo; Lela Owens; Tulsa County District Court; Getty

In a parallel universe, you could imagine the police leaving King in the care of a women’s shelter. But the detectives did not view her as a victim. That’s because of Oklahoma’s “failure to protect” law, which requires parents to shield their kids from physical harm if they’re aware or “reasonably” should have known that another adult was abusing or might abuse the child. Because of this law and how it’s interpreted, King was blamed for what happened to Lilah.

The law is “inherently problematic,” says Megan Lambert, the legal director of the ACLU of Oklahoma, who studies these cases. “A lot of times, motherhood is used as the grounds that they ‘should have known,’ simply because they are the child’s mother.” And mothers in violent relationships are especially vulnerable to prosecution: If they were abused by their partners, juries often believe they should have realized their children might be in harm’s way too. “Folks who are charged often haven’t actually engaged in any harmful behavior,” says Lambert. “They were put in impossible situations and were not able to act fast enough.”

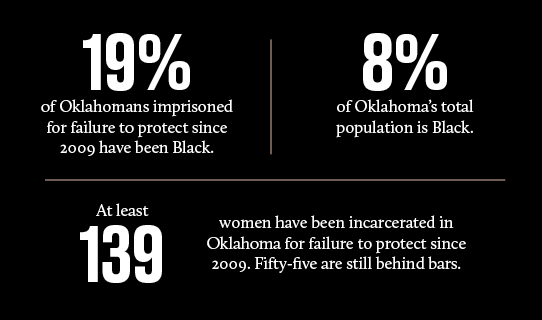

Most states have similar laws, opening the door to anywhere from a few years to decades behind bars as a punishment. But Oklahoma, which incarcerates more women for all crimes than almost any other state, has one of the harshest penalties: Moms can be sent to prison for life for their supposed failure to protect, with no exception for women who were abused themselves. The ACLU estimates that Oklahomans convicted of the offense receive an average sentence of about a decade behind bars.

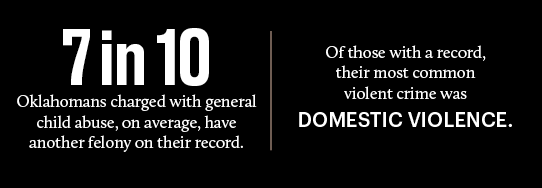

These types of laws aren’t talked about very much, but they are used to punish parents nearly every week. Last year, I found local news reports of 53 people across 29 states who were, within the span of just three months, arrested, prosecuted, or convicted for similar crimes. Many more cases go under the radar. There are no national data sets to show how many parents have been convicted of failure to protect—in part because their convictions are often labeled as “child abuse” or “child neglect,” making them difficult to track down. But if Oklahoma is any indication, an enormous number of families have been ripped apart. When my colleague Ryan Little and I conducted a groundbreaking review of the state’s court records, we identified hundreds of people who were charged under the law since 2009, when a new version of the statute went into effect.

While the language of these laws refers to parents, prosecutors overwhelmingly target mothers, not fathers. Since 2009, at least 90 percent of the people incarcerated for the offense in Oklahoma were women. Attorneys in multiple states who specialize in this area of law tell me they have never seen a man prosecuted for failing to stop someone else’s violence against a child; Mother Jones found relatively few examples. “It’s sexism,” says Lambert. “It’s the assumption that women are responsible for all the goings-on in the home.” In Oklahoma, the vast majority of women convicted for failure to protect had no prior felony record.

Women of color are disproportionately prosecuted. Black people make up 8 percent of Oklahoma’s total population but 19 percent of those found guilty under the statute since 2009. These types of laws are “really enforced in a racist and classist way,” says Stacey Wright, a women’s rights activist who has also studied these cases.

Not only are the laws used to prosecute women who, like King, are themselves victims of abuse, but there’s no proof these laws are successful in protecting kids. Separated from their mothers, children affected by failure-to-protect convictions sometimes end up in foster care or with abusive guardians, according to several attorneys who are familiar with the statutes.

These laws also create an impossible dynamic that makes survivors less likely to report what’s happening to police. When someone calls 911 after being abused by a partner, some cops open a child welfare investigation if there are kids in the family. So if a mother calls 911, she risks losing her kids; if she doesn’t, she risks being prosecuted for failure to protect. As one legal expert suggests, there’s no way to win. “It creates another barrier for domestic violence victims to seek help, because now they are also threatened with criminalization and incarceration, which also means losing their children,” says Lambert.

In essence, the criminal justice system makes these mothers ultra-culpable, blaming them for things that are largely outside their control. Mothers are punished not only for their partners’ violence, but for the violence that has been inflicted upon them—for the sexism that leads to domestic abuse, for the poverty that makes it hard to escape, for the racist policing systems that don’t protect them, for the circumstances that leave them with few options. As an untold number of women sit in prisons for these supposed crimes, their kids in someone else’s care, maybe the real question we should be asking ourselves is: Who is failing to protect whom?

At the police station, the detectives reprimanded King. During the videotaped interrogation, a female officer brought up the moment when Purdy locked the door to Lilah’s room. “You should have went and got help,” another female officer told her.

“You guys don’t understand,” King said, her voice quivering. “I was so scared myself.” She ran her fingers through her hair, near the scar on the back of her head where another man—her ex-husband and the father of her three older kids—once hit her with the butt of a gun. She had another scar from him over her eyebrow. And another near her wrist, where Purdy had cut her. “I didn’t know what to do,” she told the detectives. “I wanted to get in there and grab her away from him and hold my baby.”

“The problem is, you already held her once…while he whipped the shit out of her,” the first officer said calmly. “You should have ran for help.”

“That’s why you’re going to jail today,” the second officer said. “Because of the things you didn’t do. Your job as the mom is to protect your child.”

“And you failed,” both detectives said in unison.

They handcuffed her and prepared to lead her away. “I love my kids,” King said, crying. “I’m not a bad mom. I’m not.”

The officers did not seem to care about the abuse King had endured, abuse that began when she was just a child. She grew up in Stillwater, Oklahoma, the daughter of a Black mother who worked as a social worker and at the financial aid office of a junior college, and a white father who was a math instructor at Northeastern State University. King didn’t meet her father until she was 4.

When King was about 6, her mother, Lela Owens, grew suspicious after King accidentally peed in the driveway one afternoon while playing basketball. Owens took the girl to a therapist, who surmised she had been sexually abused multiple times. King remembers being molested by a preteen in a park when she was about 4.

As a kid, King liked animals and dreamed of becoming a veterinarian or a doctor; she wanted to take care of others. But by high school, King had lost much of that self-esteem and began hanging out with boys who used her for sex. “I wanted somebody to love me so bad, I didn’t care how they treated me,” she recalls. When she was 16, she met Ali Jordan Lalehparvaran, whom she would later marry. He was a couple of years older and seemed so sophisticated and kind. He would take her out for dinner or to the candy store for fudge. He bought her a diamond necklace. She’d never been treated that way by a boy before.

Months after they got together, Lalehparvaran learned that King had slept with other people before meeting him, and something seemed to snap. According to court records, one weekend they went boating and he smacked her on the head with an oar so hard she needed stitches. Another time, he broke her arm. But “I felt like I deserved it,” she says. “Like there must be something wrong with me…I had been very promiscuous and felt like I couldn’t do any better.”

At 20, she got pregnant with their first child, Persia. She was thrilled—she and Lalehparvaran had been trying to conceive for a while. “I always wanted a family,” she tells me. She loved the feeling of the baby moving inside her. “It’s just the most beautiful thing ever,” she recalls. She imagined putting her child in colorful dresses and fixing her hair. “I was really excited about it. I could see myself being able to take care of a girl.” She hoped that having a daughter would calm Lalehparvaran down.

They married and had two more kids, William and Lilah, and the violence escalated. While she was pregnant with Lilah, Lalehparvaran pushed King up against a wall and broke her clavicle. She left him and went to stay with her friends. But because Lalehparvaran had paid her bills, a relative told her to go back to her husband, and she did. Another night, Lalehparvaran, who was drunk, smacked a gun into King’s head and shot up their home with an AK-47. As the bullets flew, King told the kids to lie on the ground, covering them with her body. “I was in survival mode. I wasn’t thinking of anything except, I have to protect my kids,” she recalls. Lalehparvaran was sentenced to seven years in prison; they divorced in 2013.

Afterward, King struggled. She had a job at a pharmacy that paid $10 an hour, but she had just $800 in her bank account, not enough to cover the mortgage and keep the power and heat on. She tried to help her young children, who were missing their father. She showed them how to bake banana bread and solve math equations. She regularly drove them an hour away to visit their dad’s mom. On birthdays she organized parties and baked special cakes. “She was a good mother,” says Kathleen Araujo, Lalehparvaran’s aunt, who still spends time with the children. “If she loved you, she would do anything for you,” adds Melissa Williams, Lalehparvaran’s mother.

“I think a good mother is someone who can nurture them, loves them, and points them in the right direction,” King tells me. “Somebody that they can talk to, that they can rely on, that will always be there.”

She was 26 when she met John Purdy. Then 19, Purdy was handsome and athletic, with big brown eyes and chiseled, tattooed arms. And he made her laugh, a relief after such a volatile marriage. She sympathized with the challenges he’d overcome: As a boy, he’d been abused too.

In 2013, King got pregnant with their child, Trinity. “I was excited but kind of scared, because I wasn’t sure how he felt about it,” she says. Soon, court records show, the relationship took a turn. Purdy falsely accused her of getting pregnant by someone else. He started controlling her—dictating everything from her hairstyle to when and how she could use her phone.

Violence followed, she would later testify: One time he sliced through her calf with a kitchen knife and left a 2-inch cut. Sometimes he backhanded her or choked her. He did heroin in the house and demanded she join, even holding her arm down while his friend injected her. She imagined kicking him out but worried he would retaliate. “I was really scared, more than anything. I felt kind of trapped,” she says. In fact, experts say that leaving an abuser can be dangerous for women, and that many mothers with kids struggle to get away.

Purdy sometimes apologized, vowing to be better. “I believed him when he said he was never gonna do it again,” King later told investigators.

But he did.

After Purdy was arrested, Lilah went from the hospital to foster care and then to her paternal grandmother’s house, where she would stay as the investigation continued. King was devastated: “I was just in shock, just completely distraught, like I just didn’t know what to do,” she recalls of the separation from her kids. (Lilah’s older siblings, who had been living with King’s mom near Chicago, were allowed to stay there.) “It’s like my greatest fear came true.”

In jail, King was put on suicide watch, and she shivered and sweat as she withdrew from heroin. Her housemate bailed her out a few weeks later, but a court soon terminated King’s parental rights to Trinity, who was just 1 year old. Purdy also lost parental rights, but Trinity was adopted by his friend, a man who has prevented King from talking with the girl. It was “like my world was crushed,” King says. Unable to pay for a lawyer, King lost track of her court schedule and missed a hearing. As a result, she landed back in jail.

If she had any hope of getting her children back, King had to think carefully about her legal options. Her mom urged her not to plead guilty and instead to go to trial. It’s something she’s regretted ever since. “I gave her the most awful advice ever,” Owens tells me now. “I knew she wasn’t really guilty of anything, except being used and abused…[But] I should have told her to take the plea bargain.” At trial, “she went through hell, and nobody cared.”

Failure-to-protect laws sprang from changes to child abuse protocols in the 1960s, as doctors became obligated to report signs of mistreatment. The idea was to compel parents who witnessed violence to take action. But the provisions didn’t become commonplace until after a high-profile child abuse case in the late ’80s led to a media frenzy and one of New York’s first televised trials.

In 1987, according to court records, 6-year-old Lisa Steinberg died in New York City after Joel Steinberg, an attorney who had illegally adopted her, beat her unconscious. His girlfriend, Hedda Nussbaum, a former Random House editor who helped care for Lisa, remained with the dying girl for about 12 hours without calling the police; Steinberg meanwhile freebased crack cocaine in their Greenwich Village apartment. Nussbaum, also high, said she believed Steinberg had supernatural healing powers. Only when Lisa stopped breathing did Nussbaum finally urge Steinberg to dial 911.

Prosecutors initially charged them both but dropped the charges against Nussbaum when the abuse she’d endured became evident, both by her deeply misshapen face and by X-rays and exams that revealed her to be anemic and malnourished, with broken bones and chronic infections. Doctors and other witnesses testified that years of beatings from Steinberg had left Nussbaum traumatized and physically incapable of wounding Lisa, or of intervening to protect the girl.

After watching Nussbaum testify, the evidence of her abuse clearly on display, the public became deeply divided. Some saw her as a victim, but others viewed her as a co-conspirator. A People magazine cover showed an image of young Lisa and the question “How could any mother, no matter how battered, fail to help her dying child?” Nussbaum’s critics wondered why she had covered up Steinberg’s violence, and why she hadn’t cried when the police arrived at their brownstone for Lisa. In court, she even testified that she “loved Joel more than ever” while Lisa lay dying.

“Why was Hedda Nussbaum given a walk?” Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen wrote. She was “a mother who did nothing as her daughter was brutalized—who put up with the most incredible indignities herself and who, even as Lisa was taken to the hospital in a terminal coma, attempted to provide Steinberg with an alibi.”

The public backlash against Nussbaum likely helped spur lawmakers and prosecutors to ramp up passing and enforcing failure-to-protect laws, says Karla Fischer, an attorney and expert witness in Illinois who has assisted the defense of women in dozens of these cases around the country. Fischer believes prosecutors are especially hard on these mothers because of political pressure, perceived or real.

Oklahoma approved its first failure-to-protect law in 2000. It’s one of several states, including Texas, West Virginia, and South Carolina, that allow maximum sentences of life in prison for the offense. But these prosecutions are not just a red-state phenomenon. They’re “a problem nationally,” says Colby Lenz of the nonprofit Survived & Punished, who points to California and Illinois as two Democratic-leaning states where parents are often imprisoned for similar crimes. I found recent cases across the country, from Massachusetts to Michigan to North Dakota to New York.

Today, at least 29 states have laws that explicitly criminalize parents for failure to protect against abuse. In many places that don’t, prosecutors take similar actions under more general laws—like charging a woman with murder even if her boyfriend killed the child, and then using legal theories about failure to protect to convict her. Some prosecutors are now extending similar logic to fetuses, charging women who self-abort. “There seems to be a strange obsession with our lawmakers when it comes to asserting control over women’s lives,” says Wright, the women’s rights activist.

And it is almost always women who are held responsible. Alexandra Chambers, an adjunct professor at Vanderbilt who is tracking these cases in Tennessee, sees a religious underpinning of these prosecutions—springing from the Christian myth of Eve, who was blamed for the fall of Eden, and sexist traditions that dictate women be the “moral center” who rein in men’s worst impulses. “Women are judged by what their partner does in a way that men aren’t,” she says. “And it can be seen as a moral failing that she didn’t have the moderating influence” to stop the abuse.

“It becomes insurmountable, the number of things [women] have to do in order to be in compliance with what we think is a good mother,” Colleen McCarty, an attorney who worked on commutations in these cases, told Tulsa People in 2019. Clorinda Archuleta, an Oklahoma mother who’s serving a life sentence for neglect and permitting abuse while her boyfriend serves 25 years for the same charges, believes she was punished so harshly because she didn’t appear sorry enough; according to a local news organization, the prosecutor described her emotional demeanor as “flat.”

Juries are also much more likely to deem Black women as bad mothers, reflecting a structurally racist legal system. Black women face higher incarceration rates than white, Hispanic, and Asian women, and they’re more likely to experience domestic violence and poverty. Black parents also face stricter scrutiny from the child welfare system, which investigates more than half of all Black kids nationally, according to a 2017 study in the American Journal of Public Health. “Black families get scrutiny that white families don’t get,” says Cindene Pezzell, the legal director of the National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women.

On top of all this, failure-to-protect laws ignore how often abuse of a child overlaps with abuse of a parent. One 2006 study sponsored by the Justice Department found that kids are more likely to face mistreatment by either parent if the mother is being beaten by her partner. A survey of 6,000 American families found that half of men who frequently assaulted their wives also frequently harmed their children. So it’s not surprising that so many mothers locked in prison for failure to protect are also victims themselves: In Oklahoma, roughly half of the women convicted under the law between 2009 and 2018 were experiencing intimate partner violence, according to an ACLU analysis of 13 of the state’s counties. “The law should treat someone who’s a co-victim as a co-victim, as someone who is in need of support and resources, and not as a co-defendant, as someone who is in need of prosecution and incarceration,” says the ACLU’s Lambert.

Only a handful of states make exceptions for domestic violence survivors. “We weren’t thinking about domestic violence,” former Oklahoma state Rep. Jari Askins, who wrote the state’s failure-to-protect law, told BuzzFeed News in 2014. Askins argued that women in abusive relationships could tell the court about that history to receive leniency. In reality, such history is often used against them, as prosecutors convince juries that suffering through years of abuse without leaving is a sign of bad parenting.

“It’s hard for people who are on the outside looking in to understand how someone could harm their kids or submit to an abuser’s demand to do that, but survivors know what the consequence of each choice is,” says Pezzell. A mother, for instance, might follow orders to hold her daughter down or even hit her child because she believes that obeying his commands will keep him from going harder against the kid. And for these women, dialing 911 can be dangerous. “If the police don’t believe her and send her home, then she feels he’s gonna kill [her]. And if she’s dead, he has unfettered access to the child,” says Fischer, the attorney in Illinois. “Battered women are forced into a position where they think differently about what’s safe and what’s not.”

King says society has unrealistic expectations. “They think we’re supposed to be like he-man women, like super strong and able to beat men down whenever they come at us,” she says. “It doesn’t make any sense to me, how you could expect us to be able to take down a man.” (When survivors do kill their abusers, they frequently end up in prison.)

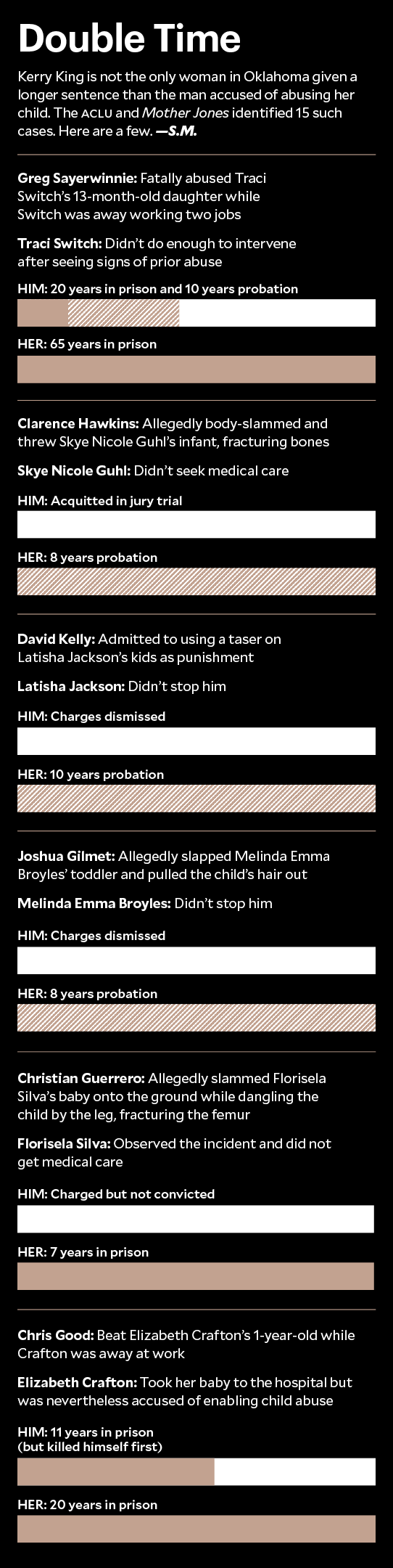

Courts often don’t consider the catch-22 that such moms find themselves in. In 2015, a man in Frederick, Oklahoma, fractured a toddler’s skull, and the boy later died. The jurors convicted the man and recommended a 17-year prison sentence. Another jury recommended that his girlfriend, who was the boy’s mother and had been asleep during the injury, go to prison for life. “A lot of the disproportionate treatment is rooted to our psyche in this state: We tend to get madder at the woman who we felt like didn’t protect the kid than we do the man who abused the kid,” says Tim Laughlin, executive director of the Oklahoma Indigent Defense System, which defended the mother in Frederick. “It seems to be part of our collective consciousness,” he adds. In Oklahoma, at least 15 women accused of failure to protect received longer sentences than their male partners who were accused of abuse. On average, these women got 20 years of prison or probation, while the men got less than eight.

Kerry King awoke before dawn on the first day of her trial, on Halloween in 2016. “Inside I was like an earthquake” of nerves, she recalls. A guard handed her a plum-colored dress that her attorney had sent for her to wear to court. Nobody had asked for her size, and it was far too small, the fabric clinging tightly to her hips and thighs. “I felt immodest, like I was stuffed into it,” she says. “Like, how would that look to the jury? I was so upset about that dress.”

When she arrived at the Tulsa County courthouse in the plum dress, King faced prosecutor Sarah McAmis, who was seeking a decades-long sentence. McAmis had told Tulsa World that it disturbed her when mothers entered romantic relationships with men they didn’t know well and then chose not to intervene against abuse after warning signs. “If you bring a child into this world,” she said, “you must do everything necessary to protect the child.” She said she believed child murder victims “are watching from heaven and…know we are able to get justice for them.” And previously she had employed an extreme tactic to win in another trial, punching and kicking a doll in front of the jury to demonstrate the injuries to a child, even though there was no evidence the child had been kicked in real life.

Her boss, Tulsa District Attorney Steve Kunzweiler, told the New Yorker in 2018 that a prosecutor’s job was to “teach people the morals they either never learned or they somehow forgot.” His approach to criminal defendants, he added, was similar to the way he disciplined his daughters: “There are times when your kids need a lecture, times when they need a grounding, and times when they need a spanking.”

McAmis began her opening statement to the three men and nine women of the jury, all but one of whom appeared white, by painting King as complicit: “[W]hen [Purdy] came back with the belt, this defendant held her daughter down.” McAmis soon called Kristi Simpson, a child welfare investigator, to the stand, and asked whether King should have done more after discovering the bruises on Lilah in the bathtub. King had stayed home from work afterward to watch her, but “it was not enough,” Simpson replied. At the hospital after the final attack, Lilah could not stay calm while she received a CT scan or an MRI. “We were trying to explain it to her,” Simpson recalled of the procedure. “And she was crying and saying, ‘Please don’t. I’ll be good. I’ll be good. I’m sorry.’”

“Myself and the medical professionals, we teared up,” Simpson added. “We had not seen anything like this.”

At a table beside her attorney, King cringed. The prosecutor’s questions, she recalled, felt “like a battering ram.” McAmis emphasized to the jury that King did not call 911 to save Lilah. And it was true, she never did. But King had tried to get help.

As King would later share in court, she had asked Purdy to shower with her when he emerged from Lilah’s room around 4 a.m. After the shower, Purdy briefly left King’s phone within her reach. When he walked away, she texted, “Help me,” to her mom, then deleted the message from the phone so he wouldn’t see it.

Moments later, the phone rang. When Purdy answered, Owens, King’s mother, who’d been roused from a deep sleep by the text, was on the other side, asking for answers. Purdy hung up and then pushed King up against the linen cabinet. What did you say to your mom? he asked before hitting her in the face. Purdy demanded that she call Owens back to say they were all just fine. So she picked up the phone and dialed.

Everything is just fine, she told her mother, trying to hide her terror as he sat on the couch opposite her, holding Lilah’s mouth closed so she wouldn’t cry out.

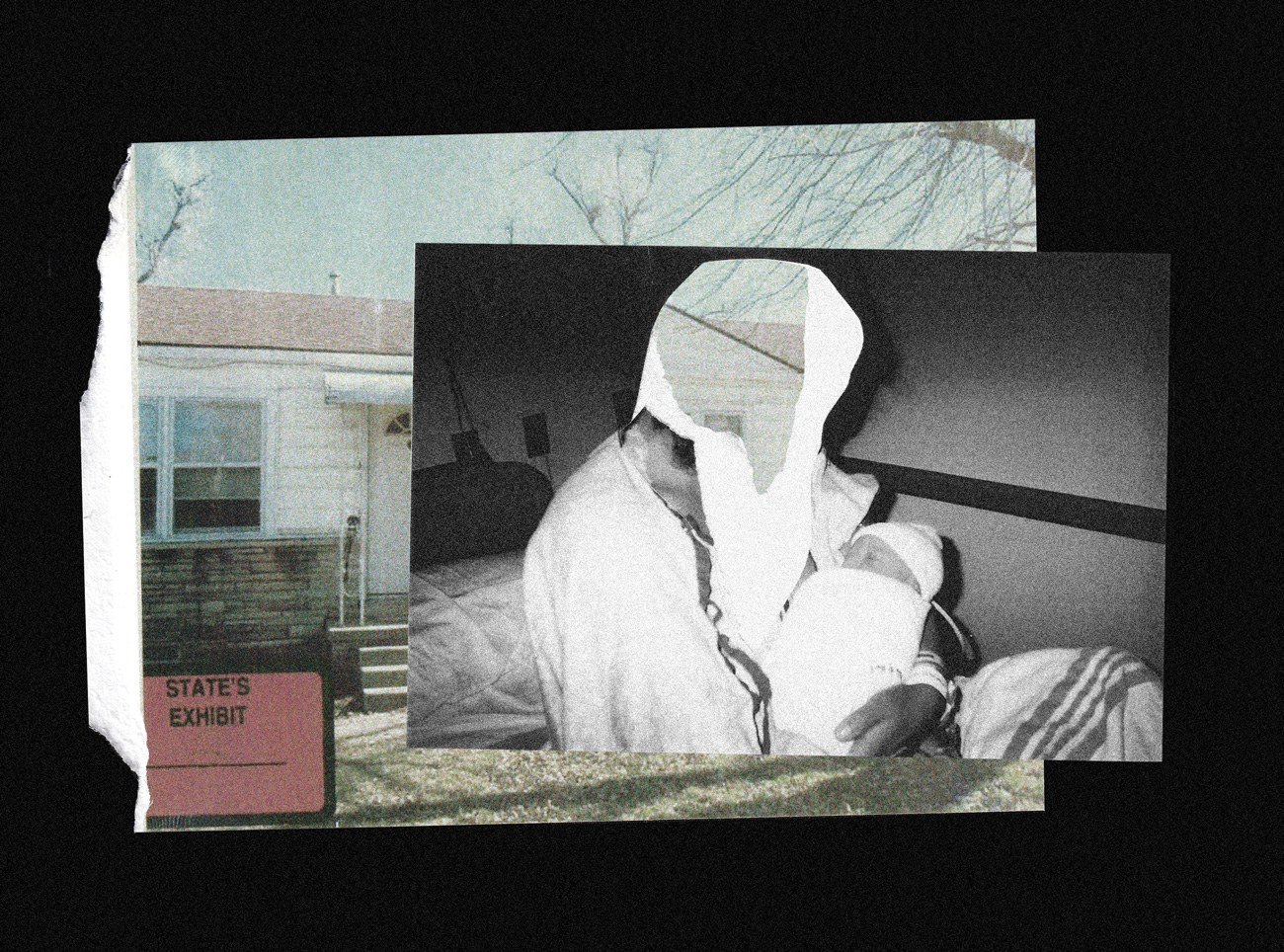

“It was like my life was over,” King says of learning of her 30-year sentence. “Like I’m not gonna see my kids grow up.”

Illustration by Vanessa Saba; Photos courtesy of: Kerry King

On the fourth day of the trial, King took the stand, hoping to finally share her side of the story. But during the cross-examination, McAmis “got under Kerry’s skin,” her attorney Brian Boeheim says. “And that nice, sweet girl that was testifying got angry and got snippy with the prosecutor. That was it for the jury. They saw her as someone who could be aggressive and could allow somebody to do this to a child.”

Testifying can be an agonizing experience for survivors of domestic violence, forcing them to recall painful moments in vivid detail. Prosecutors sometimes use the same intimidation tactics that abusers employ, retraumatizing them. McAmis suggested that King was dishonest because a few parts of her testimony did not perfectly match statements she’d made immediately after the assault; decades of research show that some survivors can recall certain moments of abuse in great detail but, because of the fear response in their brains, may have only fragmented memories of other moments.

Throughout her questioning, McAmis often framed the abuse King had endured as evidence that she’d been a bad mother to her children. “Were they having fun after they saw you get pistol-whipped and the blood gushing from your head?” the prosecutor asked her, referring to the night when Lalehparvaran shot up their home while the kids were inside. And when King brought up the ways she had also been a victim, McAmis suggested she was unsympathetic to her daughter’s injuries. “Are you telling this jury you have had a more traumatic experience than what Lilah experienced that night?” McAmis asked, referring to Purdy’s beating. “Surely you are not minimizing what your daughter went through?” she added later. (McAmis did not respond to requests for comment.)

McAmis’ approach, says the ACLU’s Lambert, is “heartbreakingly indicative of the attitude behind failure to protect. Prosecutors are using this tool for the noble purpose of protecting children from child abuse, but with the horrific method of criminalizing and vilifying the nonabusive parent who is often the victim of that same abuse.”

Before King left the stand, she kept looking over at the judge, wondering, Are you for real gonna let her say these things to me?

“This is exactly what survivors fear will happen when they tell someone they are abused,” Lambert adds. “To not be believed, and even worse to be blamed.”

During closing statements, McAmis focused on how Purdy repeatedly called King from jail and King kept talking to him.

“Those jail phone calls, they’re disgusting,” McAmis told the jurors. Then she mockingly offered her interpretation of King during the calls: “‘Bummer for you, Lilah. Mommy is still in love. You’re on your own, kid.’” On the phone with Purdy, King said she loved him and even wanted to have another child with him.

That “sunk the ship,” Boeheim, her attorney, recalls. “You could just see the jury fold up.”

Boeheim had tried to tell the jury that during the calls, Purdy incessantly begged King to say she loved him and threatened to hurt her if she didn’t. At one point he said he’d take the baby away if King didn’t stay in a relationship with him. According to a court document, he said he’d shoot bullets at her kids, kidnap her, tie her up, and rape her:

Tell me you love me. When I get out of here I’m going to drop kick you. I’m going to kick your teeth in. I’m just kidding, baby. I’m just kidding. Tell me you love me. You want to marry me. Come on, just go run down to the courthouse and you can marry me. You can marry me. Come on, we’re soulmates. Tell me you love me. I’ve got to hear you love me. I’ll carve your face. I’ll carve my initials in your face. Come on, you know I’m just joking, baby.

King talked with Purdy initially because she “wanted to understand why he did what he did,” she tells me. She doesn’t know why she kept talking with him after that. But experts say it’s not uncommon for survivors to continue engaging with their abusers, and that it can be difficult to cut ties. “I really thought I loved him,” she says.

During his closing statement, Boeheim tried one last time to convince the jury that his client did not deserve punishment because she had not been the true perpetrator. “He’s the monster. He’s the predator,” he said of Purdy.

But he may have been fighting an uphill battle. In Oklahoma, “juries are extremely punitive toward women who have children being hurt in their home,” McCarty, the attorney who has worked on commutations, tells me. “It’s a cultural more, especially in the South or the Midwest, that our job as women is to take care of our children.”

The jury deliberated for less than an hour. King’s muscles tensed as the foreman read the verdict—guilty on both counts—and recommended 30 years in prison for each. King dropped her head and started to cry.

“It was a travesty,” Boeheim says.

“I was flabbergasted,” says Araujo, King’s ex-husband’s aunt, who attended the trial.

“It was like my life was over. Like I’m not gonna see my kids grow up,” King recalls.

Only later did the jury learn that Purdy took a plea for 18 years in prison—12 years less than one of King’s sentences. “I was sick to my stomach,” juror Misty Reed, now 37 and with children of her own, recounts. “If I would have known that the boyfriend had gotten way less years, it would have definitely changed my mind” about the proposed sentence for King, she says. “And I guarantee it would have changed many others on the jury as well.” (Other jurors did not respond to my calls or declined to comment.)

With the trial over, King braced herself for the sentencing hearing. “All I ask is that you don’t make this the end of my life with my children,” she wrote to the court. The judge took some mercy and allowed her sentences to run concurrently. It was positive news, but little consolation: By the time she gets out of prison, she will be about 60 years old, and her children will be grown.

But for now they were still young and needed a permanent home. King had lost parental rights to her youngest daughter, Trinity, who was adopted by Purdy’s friend. What about the other three? The state of Oklahoma sent her daughter Lilah to live with Lilah’s father and King’s ex-husband, Lalehparvaran, despite knowing about his violent criminal record and history of substance abuse. Lilah’s older siblings, Persia and William, then 9 and 7, soon went to live with him too.

That state officials would condemn King as a bad mother for the way she had dealt with her ex-husband’s violence, and then send her young children to live with him while locking her away in prison, felt like the epitome of a double standard. “My heart sank,” King says. “I lost all faith in justice. I lost everything. What was I ever thinking in trusting a system that was not for me? I didn’t realize the depth of how much it wasn’t for me.”

King entered Mabel Bassett Correctional Center in McLoud, Oklahoma’s biggest prison for women, in May 2017. They handed her an orange jumpsuit that was too small, and a prisoner ID number and told her to memorize it. She would have one locker for her belongings: a bottle of shampoo, a tiny toothbrush with toothpaste, a bar of soap, two pairs of socks, two bras. Within a week, she watched someone get beaten with a shower rod.

In Oklahoma and around the country, the vast majority of incarcerated women are mothers: National data is scant, but studies have found that upward of 90 percent of them experienced physical or sexual violence before landing behind bars.

In 2018, King learned that she wasn’t the only person at Mabel Bassett serving time for failure to protect. Attorneys and advocates from the nonprofit Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, frustrated by lawmakers’ lack of action to reduce mass incarceration, had begun a commutation campaign to help incarcerated people petition the state for shorter sentences. Lambert, the ACLU lawyer, joined the effort and introduced King to several other women in the prison who had been convicted under the same law. All were women of color. “It made me see how messed up this state was,” King tells me. “There are so many of us in here that really should not be in here.”

In November 2019, one of them received good news. Tondalo Hall, now 38, had already served half of her 30-year sentence for enabling child abuse. Her ex-boyfriend Robert Braxton broke several bones in two of her children’s legs; he served only two years in jail before he was released on probation. Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, agreed to shorten Hall’s sentence as part of a mass commutation of more than 500 incarcerated people around the state—the biggest commutation in US history.

When Hall learned that she would be freed, she could hardly believe it. It had been more than a decade since she’d spent much time with her kids; two of her children were younger than 2 when she was first incarcerated. When she walked out of the prison gates later that week, she started crying as she hugged her family, rocking back and forth with her son Robert, now a teenager. From inside the prison, inmates cheered Hall’s reunion loud enough for her to hear them. “I love all them ladies,” Hall said to TV cameras as she looked back toward them. “I’m coming back to help a lot of them.”

But since Hall’s release, Oklahoma’s pardon and parole board has rejected all the other mothers with similar cases who applied for a commutation. Other potential avenues for relief have also closed. In 2019, advocates pressured Oklahoma lawmakers to amend the failure-to-protect law to make it more lenient for survivors of domestic violence. Yet lawmakers balked after prosecutors claimed they needed the law’s life sentence provision to properly prosecute child abuse and to use as leverage to convince mothers to testify against their abusers. Around the same time, a committee charged by the legislature to reexamine the maximum punishments for a wide array of crimes recommended that people convicted of permitting child abuse be limited to 40 years. But that change has not yet been approved, and even if it were, it would not be retroactive, doing little for women like King.

In states like California, Illinois, and Tennessee, activists are trying to help incarcerated women in similar situations, but their cause hasn’t gotten much traction. “These are hard fights,” Lenz of Survived & Punished says of the moms pushing for mercy around the country. “There’s a fear for politicians of looking like they are excusing child abuse.”

Oklahoma continues to pursue failure-to-protect cases at a swift pace. In November, a Cleveland County jury convicted 30-year-old Rebecca Hogue of first-degree murder after her boyfriend beat her 2-year-old son to death while she was away at work. Her boyfriend later died by suicide in the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, where investigators found the words “Rebecca is Innocent” carved into a tree next to his body. The judge did not allow a photograph of the carving to be shown to the jury, deeming it “hearsay” on behalf of the boyfriend. The jury recommended that Hogue go to prison for life with the possibility of parole.

During King’s first year in prison, her children were not allowed to visit her. She was furious that Lalehparvaran had received custody of them. She didn’t think he would physically abuse them—he never had—but she worried he wouldn’t properly care for them. When they lived together, it had always been on her to hold the family together, to make sure the kids had warm coats and gloves for the winter.

When mothers are convicted of child abuse crimes, some children are sent to foster care and others to live with relatives, but it’s not unheard of for them to go to a partner or ex who was previously abusive, or to the ex’s family, according to attorneys who monitor these cases. After a mother named Ashley Garrison went to prison in Oklahoma about a decade ago for child neglect, her abusive ex-husband got full custody of the kids and prohibited Garrison from contacting them, according to Tulsa People. Garrison, in handcuffs, gave birth to another child the day she was sentenced, but the baby soon went up for adoption and her parental rights were terminated. She attempted suicide in one of the prison showers.

Fortunately, Lalehparvaran seemed to have turned over a new leaf. “After prison, he’s changed; he’s a hard worker,” said Williams, his mother. Lacking a driver’s license, he rode a bicycle to the classes he needed to get certified for his HVAC job. He made sure the kids did their homework and the chores. “I think they like living with their dad. They feel safe,” Owens, King’s mother, told me. The kids said the same thing.

But even when there’s a decent guardian to step forward, losing a parent to prison can have ripple effects. According to a study by the federal government, kids with incarcerated mothers or fathers are more likely to struggle with mental health conditions like anxiety and depression, and they face a higher likelihood of medical problems as adults, from asthma and migraines to substance abuse. Teenagers with incarcerated mothers are significantly more likely than other teenagers to drop out of school and be arrested themselves.

King tried to stay in touch with her kids however she could. She called them several times a week and wrote them letters. When Persia eventually started her period, King drew diagrams to show her how to use pads. She knitted them socks and blankets with yarn she’d bought at the commissary.

But Trinity’s adoptive guardian, Purdy’s friend, doesn’t answer when King calls. King heard that Trinity likes unicorns, so she sent her a unicorn stuffed animal. No reply. She hasn’t been able to learn much else about her daughter.

About a year into her stay at Mabel Bassett, King’s older kids were finally approved for visitation rights, and they’ve been going to meet her about once a month ever since. After Christmas, King looked forward to seeing them in January, when she hoped she and Lilah might continue their conversation. But then King and Lalehparvaran had a disagreement over the phone, and he refused to bring them. She was devastated, she tells me. After all these years, she still had so little control in their relationship and much of the rest of her life.

The day after their missed visit, I met the kids at their house in Stillwater, the same city where King grew up. That evening, they planned to celebrate Lilah’s 11th birthday. In the afternoon, they sat side by side on the couch as they flipped through an album with old family photos, giggling about how they looked as babies.

But Lilah’s cheerful demeanor faded a few hours later, when, in the privacy of her bedroom, she began to talk with me about her mother’s incarceration. It still confused her. “Like, I kind of know why she’s in jail, but I know she’s not supposed to be there,” Lilah said, beginning to cry.

“I just really miss her. I just want to talk to her,” she said, imagining what it might be like to see her mom every day, not just once a month. “You can’t really make memories on a phone.”

She composed herself and went back downstairs, where she ate dinner with her family and joined a game of hide-and-seek with her siblings. Then they all gathered around the table for cake. Lilah blew out the candles and smiled as they sang to her. Her brother, William, snuck a taste of the white icing speckled with rainbow sprinkles

Dozens of miles away, King sat in prison, missing it all. In May, her ex-husband, Lalehparvaran, was arrested and charged with burglary and reckless handling of a firearm. The kids went to stay with another relative.

Lately King wonders whether someone might take mercy and grant her a commutation, let her “get out of here, be there for them, and be the mom that I always knew that I was.” Reed, the juror who spoke with me, recently got in touch with King and apologized for recommending such a long sentence.

During one of our many conversations, I ask King what she wishes people would understand about her case. “I was just as much of a victim as my daughter was, and they should not just look at that one day,” she says. “They should look at every day and see all that I went through, and how I had gotten to the point of that day.”

Project Credits

This story was published with the support of a grant from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights.

Text

Story by Samantha Michaels

Edited by Maddie Oatman

Data reporting by Ryan Little

Fact-checked by Ruth Murai

Copy-edited by Daniel King

Design

Illustrations by Vanessa Saba

Art direction and infographics by Adam Vieyra

Photo editing by Mark Murrmann

Additional image credits: Photos courtesy of: Kerry King; Kathleen Araujo; Lela Owens; Tulsa County District Court; Getty

Video

Directed and produced by Mark Helenowski

Produced by James West

Additional production by Sam Van Pykeren