This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletters, and follow them on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

There’s a body buried here—somewhere.

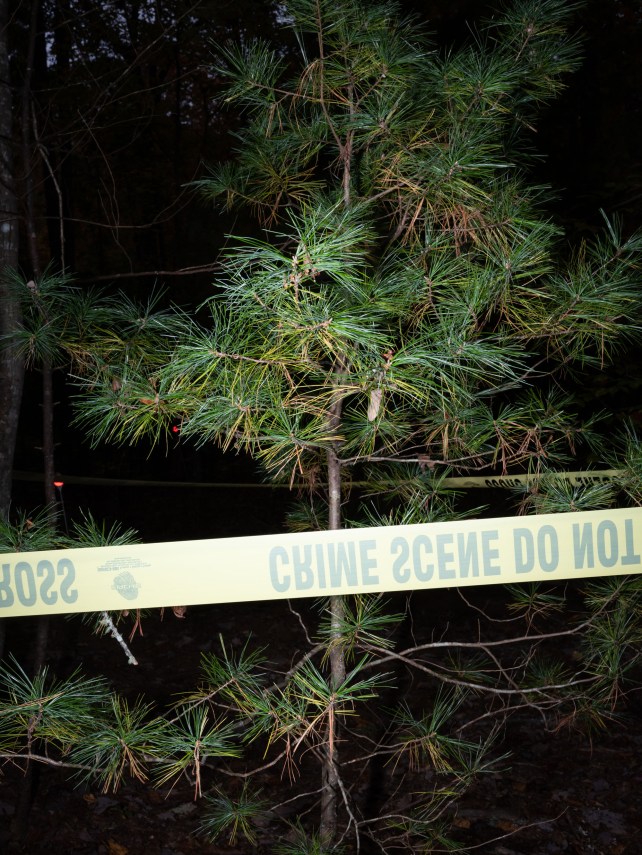

Five crime-scene investigators wearing white Tyvek suits and purple latex gloves pace through a Tennessee woodland in a slow wave, searching for areas of sunken ground and other clues that might indicate a gravesite. The chill morning air is scented with loam, leaves, and pine needles—and a hint of human decay.

The agents mark three suspicious depressions in the dirt with red flags and discuss their options for investigating further. One student asks about dowsing rods.

“You want to use some?” replies Arpad Vass, an instructor at the National Forensic Academy in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where law enforcement officers come to learn how to use science to solve crimes—at least in theory. “I use them on everything.”

There are no official dowsing rods at hand, but that doesn’t matter. “You can use the flags,” Vass offers. “Bend them like you would coat hangers.”

Fred Ponce, a private detective from Miami, with a dark mustache and beard, gets right to work. He tears the red plastic rectangles off two stakes and spaces his hands to measure about 12 inches of straight steel, then bends the remaining metal into handles. Holding the stakes like six shooters, he walks over one of the suspected gravesites. The stakes cross. He does it again. They cross. And again. They cross.

“I’m not kidding,” Ponce says, marveling that his DIY grave finder seems to be working.

Vass, a 62-year-old wearing a blue CSI Death Valley cap, is teaching his students witching, a.k.a. divining or dowsing. It’s a centuries-old practice in which a person walks a straight line holding two bent pieces of metal, or sometimes a Y-shaped twig, until they signal the presence of whatever is being sought underground. Water witches dowse for groundwater. Others use divining rods for seeking precious gems, oil, gold. Or, as in this case, human remains.

Dowsing for the dead is not exactly endorsed by scientists or forensic experts. But it is a highlight for some students attending the National Forensic Academy, a 10-week training program sponsored by the University of Tennessee. Since the academy’s inaugural class 20 years ago, school administrators say, more than 1,200 crime-scene investigators from agencies in 49 US states and five foreign countries have attended the program, which currently costs students $12,000.

The Washington Post once nicknamed the academy “the Harvard of hellish violence,” and students now wear that slogan on their T-shirts as they analyze bloodstain patterns and fingerprint corpses. They also excavate skeletons from gravesites and collect bugs from decaying bodies sprawled on the ground at a wooded site outside of town. Near graduation, instructors blow up a car for a real-life lesson on fire scenarios and explosives.

In May 2021, I spent a week at the academy, where instructors, administrators, and students described Vass as “brilliant” and “a genius.” Some students go on to use his witching technique in their own investigations. He says he is convinced his methods work.

But scholarly research doesn’t back him up. Outside experts I spoke with—professional forensic anthropologists and lawyers, as well as law enforcement officers involved with police training reforms—say they’re alarmed that a leading training program is teaching the pseudoscience of witching.

They are also concerned about the repercussions for criminal justice at a time when many mainstream forensic techniques have proved to be unreliable, including blood-spatter patterns, bite-mark comparisons, and faulty interrogation techniques. In the last two decades, hundreds of cases built on these methods have been overturned by DNA evidence.

So while dowsing for the dead may seem particularly wacky, it’s just the most extreme example of a problem afflicting the forensic practices that many Americans have seen touted on television for years, says Randy Shrewsberry, a retired police officer who founded the nonprofit Institute for Criminal Justice Training Reform. “Law enforcement regularly accepts the flaws of these practices despite the life-altering impacts that can occur when they’re wrong.”

In particular, some experts are distressed that a Vass trainee recently got witching results admitted as evidence in a Georgia murder trial. This could set a legal precedent and allow witching-based evidence to be used in other cases, says Chris Fabricant, a lead attorney for the Innocence Project, which works to exonerate wrongfully convicted prisoners. “The search for the truth is never advanced through junk science,” he says.

The academy defended the teaching of witching, saying it is only one of the techniques it shows its students. The program relies on its instructors “to relay their extensive knowledge,” Jason Jones, a forensic training specialist with the academy, wrote in an email, adding that witching doesn’t create false evidence. “You either find the remains or you don’t. You are not trying to alter anything.”

As for Vass, he says dowsing is based on scientific principles and the fact that it was admitted in court is proof of the technique’s credibility.

Cutting-edge scientists have always faced skepticism and even persecution, he says. “Galileo’s a great example. Remember what the church did to him when he said Earth was not the center of the universe?” (He was deemed a heretic and spent the rest of his life under arrest.)

Forensics—the use of science in crime investigations—dates back to 44 B.C., when a Roman physician performed one of the world’s first recorded autopsies, on Julius Caesar after he’d been stabbed to death. Significant advancements in the field came at the turn of the 19th century, with the development of fingerprint analysis and a principle formulated by criminologist Edmond Locard, the “Sherlock Holmes of France,” stating that “every contact leaves a trace.”

Examples of trace evidence include hair, fibers, fabric, minerals, and skeletal remains. Law enforcement agents have long claimed they can interpret this kind of evidence—along with impressions from blood spatter, shoe prints, and tire tracks—and use it to find and convict suspects. But DNA testing since the late 1990s has overturned hundreds of convictions based on faulty forensics. In 2009, a report by the National Academy of Sciences concluded that nuclear DNA analysis is the only forensic technique that can support claims in court that evidence matches a specific individual or source.

In 1981, the University of Tennessee was involved in an early effort to improve forensic science: a program known around the world as the Body Farm, where scientists study human decomposition by examining cadavers under different conditions over time. It has spurred a global movement to create such facilities in all sorts of climates, from arid Texas and humid Florida to the Australian bush and Canadian forests.

That program is completely separate from the National Forensic Academy, which does not do scientific studies. The academy focuses instead on teaching professional crime-scene investigators hands-on techniques they might find useful in the field. The academy describes its part-time instructors as law enforcement officers and “active practitioner-scholars”—like Vass.

His early work focused on the smell of death—the volatile organic compounds emitted by decomposing human remains. Among his inventions was an electronic device meant to help detect those compounds better than a cadaver dog. Nicknamed LABRADOR—Light-Weight Analyzer for Buried Remains and Decomposition Odor Recognition—it never launched commercially. He says he also designed a “fly on a leash,” capitalizing on the insect’s ability to find a corpse within minutes of death. He says he outfitted the bugs with miniaturized tracking devices.

“It would have worked great,” he says, “But birds eat flies. I lost most of my trackers.”

Vass was working as a researcher at a federal lab in 2011 when he testified as an expert witness in the murder trial of Casey Anthony. She was charged with killing her 3-year-old daughter, Caylee. The prosecution used Vass to try to prove that the toddler’s dead body, found in a woodland behind her parents’ home, had been placed in the trunk of Anthony’s Pontiac Sunfire.

Vass claimed that an air sample from the trunk revealed high levels of compounds consistent with human decomposition, based on his research. An analytical chemist from Florida International University testified that Vass’ testimony wasn’t backed up by scientific evidence and that many of the compounds Vass identified could have been emitted by food wrappers and other trash recovered from Anthony’s trunk.

Anthony was acquitted—in part because of doubts about the air sample from the car, legal experts said at the time.

Vass says the trial destroyed his career, and he believes it paved the way for his employer, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, to fire him. A lab spokesperson confirmed that Vass’ employment ended in September 2012 but declined further comment. Since then, Vass says, his main sources of employment have been consulting on missing-person cases and part-time teaching at the forensic academy.

The National Forensic Academy’s headquarters are in a rectangular concrete building sandwiched between an Applebee’s and a Dairy Queen on the Oak Ridge Turnpike. Classroom instruction on forensic anthropology begins at 8 a.m. with 26 CSIs sitting at long tables. Each agent has a laptop computer and a name placard. The logos on their agencies’ standard-issue black and gray polo shirts include the Texas Rangers, US Army, and Air Force, as well as private investigation companies and county sheriffs’ offices from around the country.

Lectures by a handful of teachers cover everything from bone identification and human decomposition to entomology. Vass teaches grave detection on the last classroom day, in preparation for our field trip to the program’s human burial training site.

Holding a set of sturdy L-shaped metal dowsing rods, he addresses common skepticism about divining. “You’re not going to believe it,” he says, “so you’ll have the opportunity to do it for yourself and confirm that it actually works.”

He says the metal rods can detect “piezoelectricity,” an electric charge that builds in certain solid materials such as crystals (it’s the reason quartz watches work). Bones under mechanical stress can also produce these charges, which is why, Vass says, some people can find them with dowsing rods. But not everyone, he told me, because “if people don’t have the right voltage, it’s not going to work.” (No peer-reviewed published research has illustrated that piezoelectricity can be used to detect buried remains.)

With that, he pivots to a physics lesson on Einstein’s theory of relativity and Newton’s law of motion to explain why it’s necessary to walk with a certain cadence while dowsing. He demonstrates by pacing over a cow bone placed on the floor. When the rods cross over the bone, the students gasp. Next, he shows how he uses the rods to scan larger areas by stacking them one on top of the other. The top rod swivels sharply left in the direction of the bone.

One student asks, “What’s the distance?”

Vass tells him it’s about a quarter mile. “The advantage of this is you don’t have to be on a property to scan it,” he says. “You can be on a public street and scan your suspect’s yard.”

Another student asks why the rods don’t detect the people sitting in the front row, since they’re made of bone.

“Wonderful question,” Vass says. “The electric field you’re generating from your bone is dissipating through the water and moisture in your skin, so it ends up being so weak” the rods won’t detect you if you are alive. “You have to be about two to three hours dead before this will work.”

Next a student asks how deep the technique can detect a body. “I’ve done 300 feet,” Vass says, down a collapsed mine.

“So this is accepted in court?” another agent asks, incredulous.

Yes, Vass assures them, “they demoed it for a jury, and the judge allowed it.”

Indeed, Todd Crosby, a Georgia Bureau of Investigation agent and one of Vass’ former students, testified in 2019 about how he had used “witching” to search for the body of a high school history teacher named Tara Grinstead, who went missing in 2005. At the trial of Bo Dukes, a man now serving 25 years in prison for his role in helping to conceal her death, Crosby demonstrated how the witching rods can detect bones. He testified that the technique had helped him zero in on the location where the investigators found fragments of burned human bone they believed to be Grinstead’s. Crosby says he may provide the witching demonstration again when another man stands trial for Grinstead’s murder later this year.

Crosby also guest teaches bloodstain pattern analysis at the academy. He tells me that he’s used the witching rods in maybe 40 other investigations. Of the 30 agents he supervises at the GBI, he says, about 25 have attended the academy and at least one recently used dowsing on a case.

In their demonstrations, both Vass and Crosby are careful to show that they’re not influencing the rods, which are inserted into plastic straws, allowing them to swing freely. When the students give it a go, they’re blown away. Time and again, the rods twist toward the bone. “Freaky” is how several of them describe the experience.

Scientists offer an alternative explanation for what’s happening. It’s called the “ideomotor effect,” when “suggestions, beliefs, or expectations cause unconscious muscular movements.” A number of seemingly paranormal happenings, including Ouija boards and seances, have been explained by the ideomotor effect.

Conversely, experts say credible scientific studies—double-blind experiments in which neither the dowser nor the scientist knows the location of what’s being sought—have not illustrated that dowsing works better than random luck, even when seeking water. As for bones, forensic anthropologists point to just one study, published in June 2021. Scientists from the FBI laboratory, George Mason University, and the US Army Criminal Investigation Command conducted a controlled blind test to evaluate the ability of dowsing rods to detect buried bones. A control group of participants was asked to look at nine holes and identify which ones they thought contained bones. A different group did the same using dowsing rods (which they didn’t have experience using for this purpose, according to the study). The scientists determined that neither method worked.

In a later email exchange, Vass called the study “useless,” writing that he teaches students the proper way to dowse and some of the “17 scientific principles that make the rods work which took me years to figure out.” He also said he tells trainees the pros and cons of dowsing, though the negative he highlighted when I was at the academy was that he said dowsing picks up all piezoelectric charges, including from underground power lines and animal bones.

Vass says he has given up using dowsing rods in favor of an invention he calls the “quantum oscillator.” Here’s how he describes it in class: “Everything in the universe vibrates at a very specific frequency. Gold has a gold frequency, silver has a silver frequency, and your DNA has your frequency,” he says. (Studies show DNA does indeed emit a frequency, but no research has illustrated that an individual’s DNA can be matched to a specific frequency.)

If you put a person’s fingernail clippings inside the device, he says, it amplifies their frequency and beams it out to the environment, similar to a radar gun. If the beam (which can travel as far as 75 miles, he says) finds a like object, such as gold, that object becomes “excited” and re-radiates a signal back, which then gets picked up by the device’s antennae.

The agents are flabbergasted.

One student asks, “Do you mean if you have a missing child, you can take that child’s DNA and put it in that and go to work?”

“Yeah, absolutely,” Vass says. “It doesn’t take long to find them.”

“How much does one of those things cost?” another student asks. “I’ll write a check right now.”

“I’m not selling them right now,” Vass says. “I’m just kind of assisting law enforcement when needed.” He says the device isn’t for sale because he’s concerned about national security issues. “I can tell you what room the president’s in in the White House,” he says. “ I can tell you which house has gold in it.”

Vass notes that he has a patent on this invention—though that does not convince skeptical researchers that it can find bodies. “You can patent anything,” says Diane France, director of the Human Identification Laboratory of Colorado. “It doesn’t mean that it works. It just means that the design has to be different” from other products. Like most experts we talked to, she said she had not been able to see the oscillator, much less test it.

Michael Hadsell, president of the nonprofit Peace River K9 Search and Rescue Association, which is based in Englewood on Florida’s Gulf Coast, says he is field-testing Vass’ device, and so far it has a 60 percent success rate in locating human remains. But he couldn’t provide the data to back up that claim.

Dlana Hall Bodmer says she is certain that Vass’ oscillator has located the remains of her missing 18-year-old sister, Gina Renee Hall, last seen on June 28, 1980, with a man named Stephen Epperly. Her body has never been found. Later that year, Epperly was convicted of the Virginia woman’s murder in one of the state’s first “no body” homicides.

Two years ago, Vass’ device signaled what he said was Hall’s frequency in eight locations, consistent with a theory that she’d been dismembered by her killer four decades ago, Bodmer says. With Vass, she collected dirt, small bone fragments, and a gold bracelet, which she believes was her sister’s. They’re hoping to work with a scientist who can match the materials to Hall’s DNA, or at least confirm the bones are human. Bodmer says she hopes eventually to use Vass’ invention to find abducted children. “To me that’s the bigger picture,” she says. “Somehow it’s the beginning of doing something great—that’s Gina’s light continuing to shine.”

But others who have used Vass’ services say they got nothing but heartbreak. The family of David O’Sullivan hired Vass after the 25-year-old Irish hiker vanished on the Pacific Crest Trail in April 2017.

Using his oscillator invention, Vass scanned the landscape from a helicopter and provided GPS coordinates where he said the searchers would find O’Sullivan’s body: on the north face of San Jacinto, one of the steepest slopes in the Lower 48, rising 10,834 feet from the desert floor.

A mountaineer climbed to the coordinates and scoured the area, but found nothing. Three years later, O’Sullivan is still missing.

Vass “cost us a lot of money and gave us false hope, which was much worse,” the lost hiker’s mother, Carmel O’Sullivan, wrote in an email, adding that she now doubts Vass ever found a missing person. “Families are at their most vulnerable at this time and will try desperate measures.”

In emails, Vass said he’s not out to take advantage of anybody. He charges what he considers to be a minimal fee, and says he has worked without charge in the past. He says the oscillator is just one of the many tools he uses—including canine sniffers, drones, and chemical tests—when he goes out on a case. As for the O’Sullivans, “I did my best and was out there for quite a while,” he wrote. “The area I indicated as a possible site was, in my opinion, never properly searched due to the difficult terrain.”

“Vass is operating these services that are not scientifically valid,” says Eric Bartelink, an anthropology professor at California State University, Chico, and former president of the American Board of Forensic Anthropology. “It’s very misleading to families and law enforcement.”

He’s not alone in his exasperation. Harrell Gill-King is the director of the forensic anthropology lab at the University of North Texas Center for Human Identification. “Part of the problem has to do with the fact that Vass doesn’t belong to any of the usual organizations or societies” that hold members to ethical and scientific standards, Gill-King says. “He’s operating in a society of ‘consumers’ who have been conditioned by all sorts of forensic scientific fantasy in the popular media. As a result, there is no shortage of potential victims.”

Back at the academy’s grave site, the instructors are leading teams of students. Each group gathers supplies—rakes, trowels, shovels, probes, buckets, brooms, dust pans, brushes, stakes, flags, and other tools. Vass’ team is assigned to a shady patch of forest on a hill, and provided with a simulated search scenario: A teenage girl has witnessed her dad burying a body in the forest. She confides in her guidance counselor, who reports the incident to the police. This team of CSIs is charged with finding the burial site.

They search for signs of soil subsidence and mark several suspicious areas. After Ponce, the detective, gets a hit from his dowsing rods, the team probes the soil. But the ground is too firm and tangled with tree roots. At the next location, they skip the dowsing rods and just probe. Discerning that they’ve found a likely gravesite, they mark the perimeter with flags, set up a search grid with string, and start troweling clumpy clay dirt into dust pans and buckets. Over the course of the afternoon and the next day, they expose a skeleton.

With the excavation complete, Vass wants to discuss one last thing: the divining rods. “From the holes, it appeared to me that maybe an animal had burrowed down in there,” he tells Ponce. “If an animal like a little mouse died there, you’ll get a false positive. So just pay attention to that in the future.”

The teams pack up their gear and carefully return the bodies to their gravesites, covering the cadavers with heavy shovel loads of dirt. There the corpses will remain until the next class of students arrives to dig them up.

Correction: A previous version of this article misidentified where Randy Shrewsberry served as a police officer; he worked for departments in Ohio, Indiana, and South Carolina. The article also said incorrectly that Steven Epperly’s “no-body” conviction in 1980 was the first in Virginia and fourth in the nation; there had previously been others. The article has also been updated to clarify the kinds of claims DNA testing can support in court according to a report by the National Academy of Sciences.