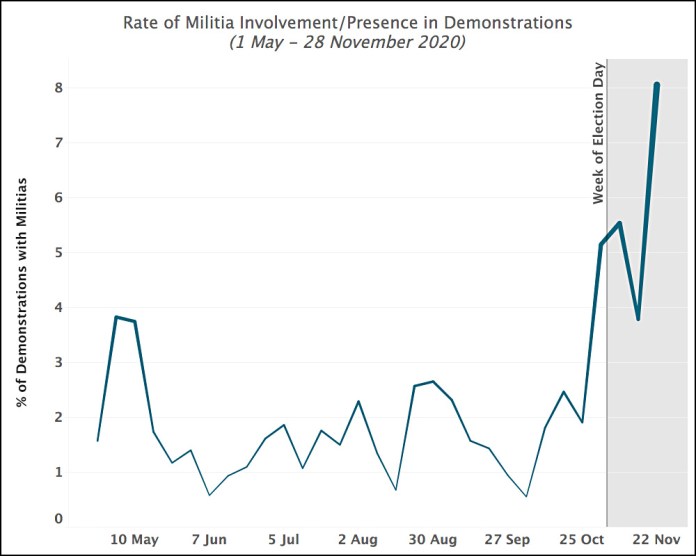

The Quinto-Collins family. Angelo Quinto is at far right.Law offices of John Burris

Angelo Quinto had two fears: death and the police. He always told his mother to comply with the cops—don’t say anything, just follow along. So when the police extricated him from his mother’s arms, his only words were: “Please don’t kill me. Please don’t kill me.”

“Whenever I think about what happened that night, it doesn’t make any sense,” his mother, Cassandra Quinto-Collins, says. “I was just hugging him. He didn’t resist. He complied.”

As an official matter, her son died in a hospital on December 26—of what, exactly, the authorities have not said. But Quinto’s family says the 30-year-old Navy veteran was killed three days earlier in his Antioch, California, home, after cops took turns kneeling on his neck until he lost consciousness—the “George Floyd” technique, as the family’s lawyer calls it. There’s video of the aftermath. Quinto is limp, and blood appears to be flowing from his mouth as two police officers attend to him. “Can you take him, please? Please, please,” Cassandra Quinto-Collins says, out of breath. “What happened?”

Last week, Quinto’s family filed a wrongful death claim against the Antioch Police Department. I spoke with his mother, sister, and stepfather over Zoom on Tuesday, with their lawyers present. The family members held each other close and cried as they recounted what happened during, and after, the night Angelo Quinto’s two great fears came together.

Earlier on December 23, Angelo Quinto had been gripped by one of his “episodes,” as the Quinto-Collins family had labelled them. He’d been having these episodes since the beginning of the year—bursts of extreme paranoia that were never violent, according to his sister, Isabella Collins. During previous episodes, he would ask questions: What’s happening? What are you doing? Can you stay with me?

“He just needed reassurance,” Isabella says. This time, the reassurances didn’t come as quickly, in the family’s telling, and Quinto grew increasingly paranoid and fearful. He insisted his mother and sister stay close to him. He interlocked their arms at the elbow—mom on the left, sister on the right—and began to move around the kitchen of their Antioch home without a clear destination in mind.

It was Isabella who called the police. This episode had started to feel different, unpredictable—her brother was being physical with them in a way he had never been. She and her mother became concerned; Isabella threatened to call the police. Angelo didn’t seem to understand. He kept asking, “What’s going on?” But he was gripping his mother’s shoulders too tightly and ignoring her cries of pain. “My brother is hurting my mom,” Isabella told the police.

Antioch police officers arrived to find Quinto and his mother on the floor. She had him in a bear hug—as much to comfort him as to restrain him, Isabella says. The cops pulled Quinto from his mother, and soon one of them was kneeling on his neck, then switching off so the other cop could kneel on his neck. By the family’s estimate, the police kneeled on Quinto’s neck for more than four minutes in all, even after he’d gone silent and stopped responding.

Since 2015, the Washington Post reports, nearly a quarter of people shot and killed by police had a mental illness. According to the Treatment Advocacy Center, police are 16 times more likely to kill a person who has an untreated mental illness. Advocates of police reform see the police, who receive a median of eight hours in crisis intervention instruction, as under-equipped and untrained to deal with these situations.

The Quinto-Collinses don’t understand why, when police entered and saw Angelo and his mother together on the floor, he had to be removed from her grip. They do not understand why one officer quipped, “Oh, wow, mom is strong.” They do not understand why officers had to fold him up, handcuff him, and kneel on his neck.

This is what the family has alleged in its claim. The officers who kneeled on Quinto’s neck, they say, left him brain-dead before he got to the hospital. (The Antioch Police Department has not responded to a request for comment.)

“This should not have happened,” says John Burris, the storied civil rights attorney representing the family. “All they had to do was talk to him. He was never treated as a real human being.”

When the paramedics arrived and he was finally rolled over, Cassandra saw her son’s bloody face, and his eyes in the back of his head.

“That’s the vision I want to take out of my mind,” she says, her daughter comforting her. “I knew, [at] that time, he was dead.”

Quinto officially died three days later, surrounded by family, with his mother holding his hands.

George Floyd died in May of last year, after a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes, setting off a nationwide reckoning in the movement for racial justice and police reform. The killing was soon followed by a smear campaign that attempted to justify Floyd’s asphyxiation. We learned, for instance, that Floyd had had fentanyl in his system, and that he had been in legal trouble before. Like Mike Brown before him, Floyd was “no angel.”

It turns out Quinto’s death evokes Floyd’s in more ways than one. The family has lots of questions about the behavior of the police in the aftermath of their encounter with Quinto. Why did the cops seem so determined to prove that Quinto or perhaps a family member had done something wrong? They asked questions about drugs, medications, whether Angelo ate. “Did you hit him?” they asked Cassandra.

The Quinto-Collinses were confused by the questions. All they got when they pushed back was resistance.

“No matter what you said, they came back with the same questions over and over,” says Robert Collins, Angelo’s stepfather. Cassandra and Isabella were then carted off to the police station, where they waited nearly two hours for the officers to question them. Angelo’s younger brother and Robert were made to wait outside the house on the driveway.

They weren’t allowed back into their home for hours, strung along by police officers searching the house. And when the police were finally done, the Quinto-Collinses found Angelo’s room in disarray. They also found a warrant (which they provided to Mother Jones) that authorized the police to seize property that “tends to show that a felony has been committed or that a particular person has committed a felony.”

Says Burris, “That really was to try and find evidence…he was a bad person, that he was operating in illegal activity, that he had some drugs in his room, he had weapons in his room—whatever they could find that would be illegal, to somehow muddy him up, to project him in a negative light.”

Antioch police collected, among other things, two cellphones, several photographs, and five vials of Angelo’s blood.

On Monday—two months after Quinto’s death and a month after the San Jose Mercury News broke the story—Lamar Thorpe, Antioch’s mayor, held a press conference on police reform. He mentioned Quinto, but offered no comment beyond condolences to the family.

Still, chief among his proposals was a “Mental Health Crisis Response Team,” not unlike the “Street Crisis Response Team” set up by nearby San Francisco last November. Similar Crisis Intervention Teams have been set up in 2,700 communities, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness. The small body of research around them suggests they are effective in reducing arrests.

The city has otherwise been quiet about the incident, dispensing information to the public only when pressured to. The Quinto-Collinses are just as much in the dark as anyone else. The family has received three documents regarding the death of their son and brother: the search warrant, a bill for the paramedics ($3,800), and the results of a blood test they had to fight to see.

After Angelo was taken to the hospital, Cassandra and Isabella were told by an officer that in these “cases,” the patient is given a fake name, and the family would not be able to get information about Angelo’s condition.

Still, early the following morning, the doctor called Cassandra while they were at the station, asking for her by name. A police officer rushed her off the phone. She never got to speak to the doctor.

At 6:30 a.m., Robert spoke to a doctor who expressed surprise that Angelo was alive. When he hung up, he says, a detective immediately started trying to reassure him that Angelo was in good shape.

“They constantly try to tell you the situation is very different than what it is,” he says. “I’m not really sure what the overall strategy is, except to keep you confused.”

On December 25, after a day of trying, the Quinto-Collinses were able to see Angelo. “It was heartbreaking,” Cassandra says. He was in a weak state. Medical personnel had had to tape his eyes shut, and he was on a breathing machine. He was unresponsive except for a faint heartbeat.

That day and the next, they say, their attempts to get answers went nowhere. Eventually, a nurse allowed them to peek at Quinto’s blood test over her shoulder—just enough to see everything was negative for drugs—but didn’t provide them with a copy.

“Instead of looking to see what could be done better,” Robert says, “it seems like the system closes in on itself. It’s about hiding what happened and obfuscating the facts.”

The family wants to see changes to police training for mental health situations, in order to create a “process that treats mentally impaired people humanely,” as Burris puts it. And they hope that this is, at least in Antioch, the last case of police asphyxiating a mentally ill and unarmed man.

Of the police, Cassandra Quinto-Collins says: “I trusted them. I thought they knew what they were doing.”