Tiffany Crutcher, center, the twin sister of Terence Crutcher, who was killed by a Tulsa police officer, marches with the Reverend Al Sharpton in 2016.Sue Ogrocki/AP

This piece was originally published by the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, nonpartisan investigative news organization in Washington, D.C.

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, where Black residents are three times as likely as whites to have police officers use force against them, Tiffany Crutcher is on a mission to get civilian oversight.

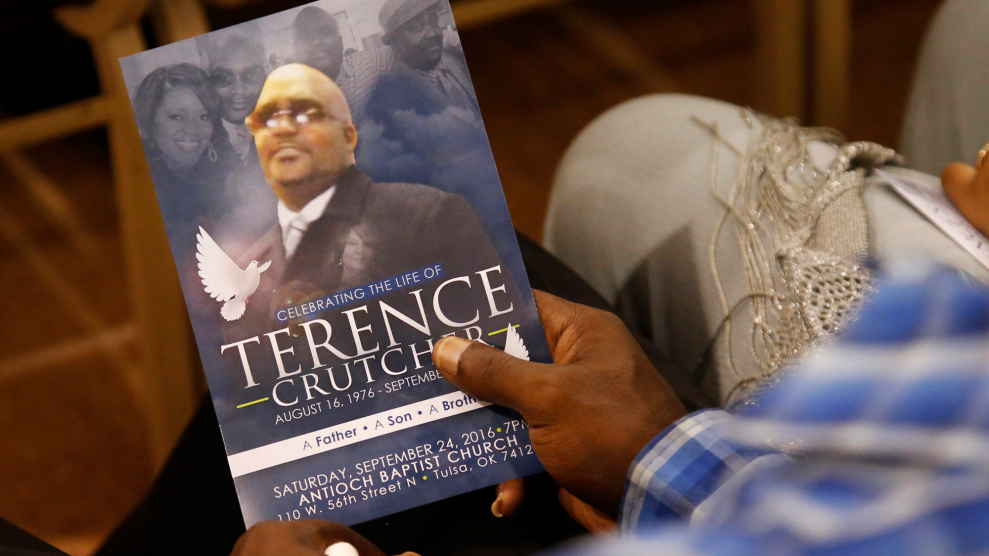

More than 140 such review bodies are operating nationwide, but the influence they have varies considerably—many don’t have much. An oversight proposal supported by Tulsa’s mayor last year struck advocates and some city council members as too weak. Crutcher—whose brother was outside his stalled SUV in 2016 when a Tulsa police officer shot and killed him—wants a review agency with enough authority to prompt change.

The weekend after George Floyd died gasping for air under an officer’s knee in Minneapolis, hundreds joined Crutcher in a march toward Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum’s house. The following Monday, she and other advocates met with Bynum and his police chief and extracted a promise: The city, which says its collective bargaining agreement with the police union stands in the way of stronger oversight, will attempt to negotiate for that authority in arbitration.

As people protesting police brutality nationwide push for broad reforms, strong civilian oversight is one of the demands. But it’s hard to get. The story for more than 70 years has been a struggle between community advocates working to enact it and police trying to block or defang it, with elected officials choosing sides. State laws often serve as stumbling blocks. And year after year, officers keep killing unarmed people like Crutcher’s twin brother Terence, many of them Black men.

The mere presence of an oversight body is no cure-all: Minneapolis has three. Richard Rosenthal, who ran oversight entities in two U.S. cities and one Canadian province, said keys to success include wide-ranging access to police information, paid staff to dig in, a mandate to look at systemic issues as well as individual complaints and political support for recommendations.

“Avoid doing it on the cheap,” he said. If elected officials create an office that meets the bare minimum to look like oversight, “in the end, it’s not going to have the impact.”

Communities keep trying: Roughly a dozen oversight entities were started in the last year or two, according to the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement. The group has been inundated with calls in recent days from people who want to create or strengthen local oversight.

“I can’t emphasize enough that we want community oversight with real power,” said Crutcher, who put her work at her Alabama physical therapy clinic on hold to focus on Tulsa police reform. “The fact is, this keeps happening over and over again without consequence. Nobody is held accountable.”

A question of power

The first civilian police review board dates back to the 1940s. But many early examples of community involvement in policing, including in the 1960s, “were really PR efforts,” said Samuel Walker, emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

“Police chiefs would create these community advisory committees,” he said. “They were always people he picked.”

In 2000, despite renewed efforts to make citizen review meaningful, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights concluded that the system as a whole remained weak. Most review boards could do no more than make recommendations, the commission said, and few had subpoena power to extract records and ensure witness testimony. Efforts to strengthen these bodies were often met by stiff resistance from police.

A good deal of what that report described 20 years ago remains true today. Half the panelists on the Minneapolis Office of Police Conduct Review, for instance, are police officers—a structure that replaced an all-civilian office in 2012 with the hope that it would improve relations between the community and its police.

The new body has upheld less than 19 percent of the roughly 2,000 complaints they considered from 2013 through 2019, according to statistics provided by the city. Nearly all involved relatively minor infractions that were handled with “coaching,” Andrew Hawkins, chief of staff for the Minneapolis Department of Human Rights, said in an email.

Just 39 complaints over those seven years led to formal discipline. And most of those weren’t ones filed by the public, said Dave Bicking, a board member of the Twin Cities watchdog group Communities United Against Police Brutality.

“Officers treat this whole process as a joke, literally, to the point where we heard many, many stories from people who have been involved in something and say to the officer, ‘I’m going to file a complaint against you,’ and the officer laughs at them,” Bicking said.

On Sunday, after days of protests, nine of the City Council’s 13 members vowed to scrap Minneapolis’ police department entirely and build a replacement with community input.

But examples of successful oversight are multiplying, said Rosenthal, now a member of the monitoring team overseeing court-ordered changes to Cleveland’s police agency. Federal lawsuits brought by the Obama administration against police agencies with a pattern of abuses, an effort the Trump administration has largely stopped, helped prompt some improvement. In other cases, communities are trying new ideas on their own.

While just 34 percent of review agencies such as Minneapolis’ said the police “frequently” or “very frequently” put their recommendations into practice, 72 percent of civilian monitor and auditor offices said the same, according to a 2016 report Rosenthal co-wrote. Those bodies represent another type of oversight model, one more likely to have paid staff with training to evaluate police practices and data. Monitor and auditor agencies now account for roughly a quarter of U.S. civilian police oversight, the report found.

Whatever the model, there’s an increasing focus on civilian oversight of policies and training—the “before” rather than just the aftermath. “It’s a lot better to change the conditions that lead to needing to have accountability,” said Brian Corr, immediate past president of the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement.

Police unions and associations contacted for this story either did not respond, declined to comment or said they were too busy to talk.

‘It takes a community effort’

Denver’s Office of the Independent Monitor receives high marks from Walker and other experts for its effectiveness. In 2018, for instance, following pressure from Denver’s monitor, the city’s Police Department revised its use-of-force rules. By mid-2019, use of force incidents during arrests had dropped 21 percent.

“Overall, the Denver model—the Office of Independent Monitor—is working,” said Xochitl Gaytan, co-chair of the Colorado Latino Forum, whose first name is pronounced Sochi. “And it can do better, but it takes a community effort.”

That sustained work by the community is a key part of the office’s power, said Rosenthal, the first person to lead the city’s independent monitor office. City and police leaders know they’ll face political consequences if they ignore its recommendations.

Gaytan and other local advocates want to bring about broader changes than a monitor is designed for—like investing more in services that strengthen neighborhoods, such as housing and healthcare, and less to police them, often referred to as “defunding the police.” But they see the monitor as part of the reform story. There’s decades of trauma they don’t want repeated in yet more generations.

“I was a teenager the first time a gun was pulled on me by a police officer,” said Ean Tafoya, co-chair of the Colorado Latino Forum. “My father and my grandfather were both shot by police officers and lived.”

In Nashville, the city’s civilian oversight office owes its life to community activism: It was born via ballot measure in 2018. Voters resoundingly approved it despite more than $500,000 in spending to defeat the proposal by the local Fraternal Order of Police, which said the agency would drive a wedge between police and the public, the Tennessean reported.

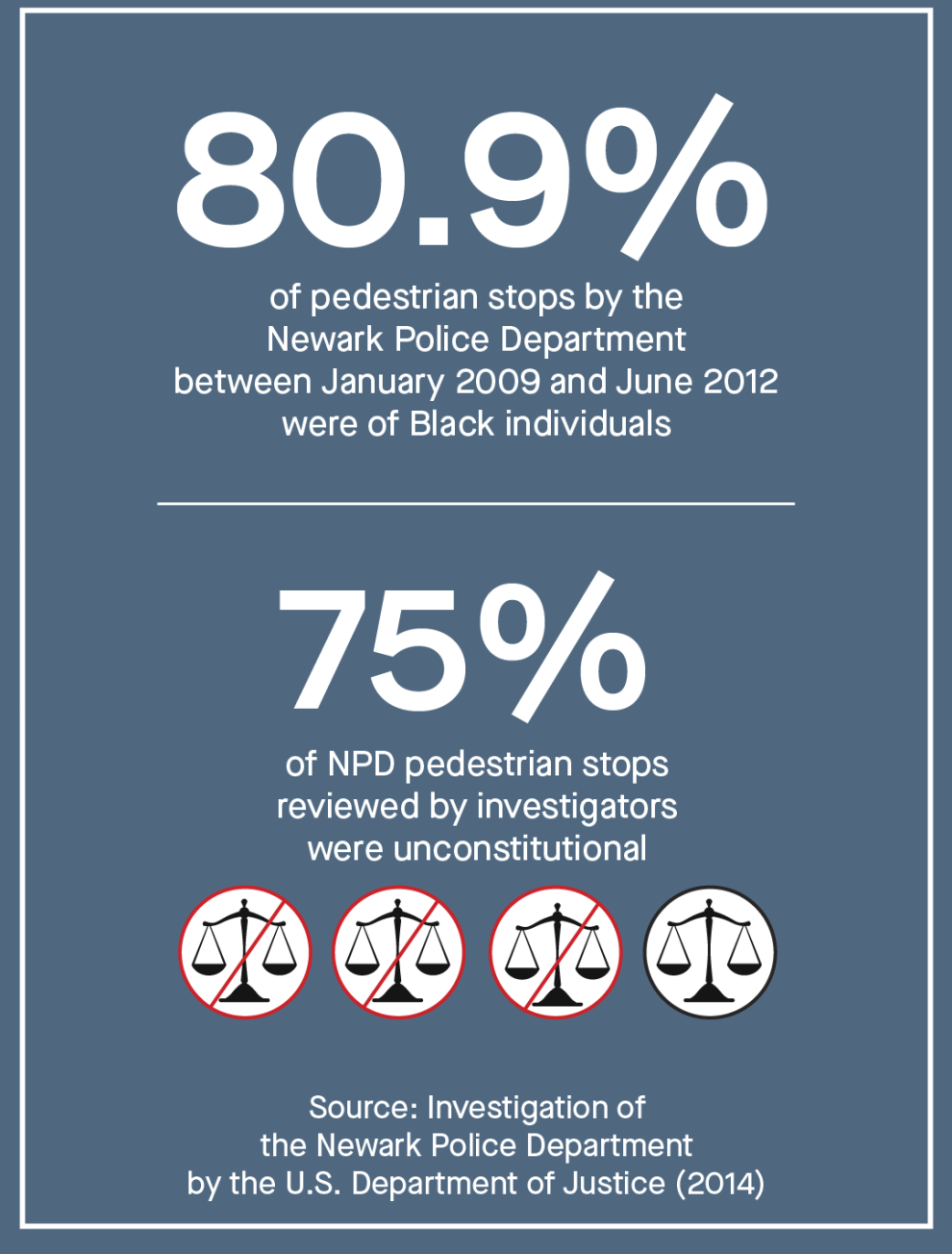

Newark created a Civilian Complaint Review Board two years earlier—decades after the first calls for one—and its level of authority is an ongoing fight. The body lost its subpoena and investigatory powers in 2018 after Newark’s Fraternal Order of Police sued. The board regained them on appeal and now awaits a decision from the state Supreme Court. But there’s a separate, though temporary, independent monitor in place as part of a federal consent decree with Newark over unconstitutional stops, searches, arrests, excessive force and theft by city officers.

Residents most affected by that police abuse were mainly Black, part of a long history of police brutality in Newark that includes the beating of John W. Smith into paralysis after he drove his cab around a double-parked police car in 1967. Five days of intense protests followed.

The work by the consent decree’s independent monitoring team includes community engagement through forums, an annual survey, quarterly reports, and both giving and soliciting feedback on procedures such as police training.

Andrea McChristian, law and policy director at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, a Newark nonprofit that is part of the monitoring team, said the creation of community service officers in the last few years—police officers whose role is to act as a point of contact for Newark residents in each of the city’s wards—was a critical part of the culture flip needed to improve relationships between the department and its community.

Advocates think the peaceful nature of Newark’s protests over Floyd’s death is due not only to the efforts of local residents but also to recent changes in policing. Among them: de-escalation training—required by the consent decree—and deciding not to send police equipped with military gear to the protests.

Newark police have largely complied to the consent decree’s requirement to develop new policies and train officers accordingly, McChristian said. It will take time to analyze how successful these strategies have been, she added.

“No matter what strategy we take, whether it’s alternatives to policing or traditional police reform, we need to make sure that the community voice is a focus of everything,” McChristian said. “It’s time to really shift towards: What do communities need to feel safe?”

Sue Ogrocki/AP

In Oklahoma, a brewing battle

In Tulsa, the push for an independent monitor met with union opposition from the start. Union officials said the City Council provided enough oversight, and they heaped criticism on the Denver monitor office that Tulsa’s mayor and police-reform advocates looked to as a guide.

“The Denver model dramatically increased violent crime and did not show an increase of trust within the community once implemented,” Jerad Lindsey, chairman of the Tulsa Fraternal Order of Police, told the Tulsa World. He did not provide data to back up those claims. Federal Bureau of Investigation statistics show Denver’s violent crime rate falling roughly 8 percent between 2005, when the monitor’s office launched, and 2018, the latest numbers.

Reached for comment, the union’s president, Mark Secrist, said by email that it would not be appropriate to speak on the matter because the group is now in discussions with the city about the proposal.

Amy Brown, deputy mayor of Tulsa, said the City Council would first need to pass legislation creating an oversight office. But what that office can do must not affect police working conditions because state law requires those changes be subjected to collective bargaining. The city will work to get broader authority when union contract negotiations reopen, potentially as soon as October.

Tulsa recently created mental-health and community-engagement units in the police department to prioritize some of the work the mayor hoped an oversight body would take on, Brown added.

“There’s been a lot of good work happening in the last few months,” she said.

Crutcher, who has a clinical doctorate in physical therapy, wants proactive improvements that will decrease risks to residents when they come into contact with police. But she also thinks a strong oversight body would ensure that officers face consequences when appropriate. The officer who killed her brother was charged, but ultimately acquitted. The case was brought over the objections of the union, which filed an ethics complaint against the district attorney who filed the charges. Had oversight employees been involved, Crutcher is convinced the investigation would have been more rigorous.

That’s proved true in New Orleans, said Susan Hutson, that city’s independent police monitor since 2010. Her office is on the scene whenever police action results in death or hospitalization. After police shot and killed unarmed 20-year-old Wendell Allen in a 2012 raid, she said, it was a monitor employee who figured out that an officer had a recording of the incident—audio evidence that showed the official story was false. A police officer pleaded guilty to a charge of manslaughter.

“We’ll make sure evidence is being preserved, that officers are not allowed to speak to one another [before investigations],” said Hutson, president of the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement. “We’ve made numerous recommendations.”

Between that, a court-ordered reform plan and the department’s own efforts, Hutson said she’s seen big improvements in local policing.

Crutcher, for her part, is cautiously optimistic about the future of police reform in Tulsa, a city still grappling with the 1921 massacre of as many as 300 Black residents by white people who were never prosecuted. But she had to upend her life to get this far.

The work extracts a heavy toll.

“I didn’t choose this. I was thrust into this,” Crutcher said. “And I’m exhausted, because I’m tired of having to wake up every single morning to fight for my life because I’m Black.”