Mother Jones illustration; Getty

We’re winding through a residential neighborhood in Framingham, Massachusetts, when the radio beeps. From the back seat of officer Jose Goncalves’ police cruiser, Danielle Larsen stops typing and listens. “Well-being check,” a dispatcher says, reading off an address; it’s outside Goncalves’ coverage area. “The occupant called to say her boyfriend is not waking up. Concerned about drugs in there. Going to get the fire rolling.” Goncalves keeps driving in silence.

Three minutes later, the officer makes an abrupt U-turn and pulls over. Through the front window of the cruiser, we see a man in his mid-30s, wearing jeans and a ball cap, head down near a curbside trash can, nodding out. Goncalves picks up his radio, says, “Going over to a male hunched over right by Gallagher Park,” and jumps out the door.

Larsen stays put, barely looking up from her laptop as Goncalves approaches the man. Goncalves asks for his ID and reads his license number into the radio—no outstanding warrants. The two stand on the sidewalk, an arm’s distance apart, their faces neutral. Then, the man adjusts his hat, pulls up his jeans, and heads down the sidewalk. “He’s on his way,” Goncalves says into the radio. “Clear.”

Goncalves climbs back in his cruiser and shifts into drive. No one says a word.

The exchange feels unremarkable, and that, Larsen argues, is what’s so remarkable about it. She isn’t Goncalves’ partner but a “co-responder”—a clinical social worker embedded in the police department to offer help to people rather than tossing them in jail. Until recently, that man, or anyone suspected of using drugs, might have ended up in cuffs. But now, Larsen trusts that officers will take a different approach—so much so that in April, when I accompanied Larsen on a Friday evening shift, she didn’t feel the need to jump out or really even monitor Goncalves’ interaction. “Rather than treating him like he was a criminal nodding off on the side of the road, on a main street, he had a conversation,” Larsen tells me later. “Basically assessed for safety and moved him along.”

While there are more and more stories about progressive policing efforts across the country and a purported drawdown in the war on drugs, society overwhelmingly treats people who use drugs as criminals who deserve punishment, not as patients with a chronic disease. National data shows that arrests for drug law violations continue to climb. At the same time, there are few signs the crisis is abating. In 2017, more than 70,200 Americans died of overdoses (the apparent peak of drug deaths), and, between 2010 and 2018, deaths from opioid-related overdoses more than tripled in Massachusetts. “Nobody was calling the police to save their friend that was overdosing because they didn’t want to get caught,” Larsen says.

“That’s why people were dying,” she adds.

Massachusetts has been hit hard, particularly by the rise of fentanyl—but it’s now also at the forefront of testing new ways to respond.

Recent law-enforcement initiatives underscore how police are trying to do the right thing, but also how they’re scrambling to fill a void. “God, how broken is our system that this is our response?” says Dr. Sarah Wakeman, medical director of the Mass General Substance Use Disorder Initiative. “Imagine if, at the height of the HIV epidemic, our response was to send police officers out with an outreach worker. We’re in the midst of a public health crisis, we have treatments that we know work, and so why is this our response?”

Public health researchers have highlighted the structural and social determinants of this “relentless epidemic”—the trauma, stigma, and social isolation that often occur together, or are underlying factors, in substance use. When social worker Sarah Abbott embedded with Framingham police in 2003, the first such clinician to do so there, she focused broadly on mental health calls. But today, Abbott understands how closely tied addiction is with mental health—as she puts it, “trauma is the epidemic.” She now serves as a director at Advocates, Inc., a nonprofit social service agency, where she and Larsen coordinate the jail diversion program. Their agency also offers training for social workers. Advocates was the first program in Massachusetts to implement a co-responder model where social workers embed inside police departments and alongside patrol officers. The agency now coordinates one of the largest such programs nationwide, overseeing 10 clinicians staffed in police departments across Massachusetts. The concept has paved the way for several other communities in New England to hire social workers, addiction coordinators, and recovery coaches to co-respond and conduct “post-encounter” follow-ups on emergencies that involve substance use.

Abbott admits that her first ride-along “was a radical proposition at the time.” While police and social services traditionally work in parallel, often with the same patient populations, “those entities have never communicated, or only communicated in a crisis, when communication is not at its finest—especially for police,” Abbott says. “Police just rolled their eyes when I get started…They really distrust civilians as an industry.”

But over the past few years, there’s been a tangible shift. Larsen says the conversation with someone who overdosed used to go something like this: “Listen, I was just on the scene. You were blue. You were dead. Let’s get some help.” Reflecting on that now, she says, “We thought that was going to get through to people. It wasn’t.” Officers and medics would end up seeing the same people repeatedly, sometimes two or three times in a single shift. So over time, more and more police departments began to look for ways to connect people who use drugs with treatment and social services outside of the criminal justice system. And in turn, they would increasingly invite clinicians to collaborate. Since 2011, Advocates, Inc. has more than tripled the number of departments it works in, for a total of 16.

Among them is Watertown, where opioid-related deaths jumped 600 percent in a single year. Since 2016, Watertown Lieutenant Dan Unsworth says he’s learned more about addiction from his opioid task force than he did in more than two decades in law enforcement. Due to staff turnover, Watertown police worked briefly without a social worker, and Unsworth says he noticed: “I feel naked even going a few weeks without one.”

The concept of better equipping police to intervene in crisis situations traces back to 1987, when officers in Memphis, Tennessee, shot and killed 27-year-old Joseph Dewayne Robinson, who was reportedly high on cocaine and cutting himself with a knife. In the aftermath, law enforcement developed crisis intervention training (CIT), also known as the “Memphis model,” to train police to assist, rather than arrest, people exhibiting signs of mental illness. CIT has been implemented in an estimated 3,000 of the 15,000 police agencies nationwide, and it typically involves dozens of hours of specialized training for officers. Research suggests that CIT reduces the number of arrests and tends to improve officers’ confidence in responding to people with mental illness. Still, the results are by no means definitive or uniform.

The Massachusetts approach spearheaded by Abbott takes a page from the Memphis model, but instead of focusing on training police officers—CIT’s hallmark—it pairs the patrol officers with civilian co-responders. Over time, Abbott says, as the overdose crisis worsened and East Coast heroin has become increasingly contaminated with fentanyl, the emphasis morphed from broader mental health issues toward substance abuse specifically.

The co-responders—from Advocates clinicians to recovery coaches employed directly by several towns—offer a wide spectrum of resources: information about obtaining naloxone; finding Hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS testing; referrals for outpatient therapy, voluntary rehabilitation, a sponsor; and sometimes simply notifying patients’ health care providers of their overdose. “I think police are coming around to the idea of ‘How do we help this individual?’” says Samantha Reif, a substance abuse program coordinator in Wilmington since 2017. (While Reif takes a similar approach to Advocates, she is employed directly by the municipality.) When she co-responds with officers, Reif says she is not trying to elicit the same information as her uniformed colleagues. Instead, she’s asking questions like, “How do you stay safe and continue to use?” “You’re ready to be sober, what does that look like?” “You’re feeling suicidal, and you want to get help. Let’s take that step.”

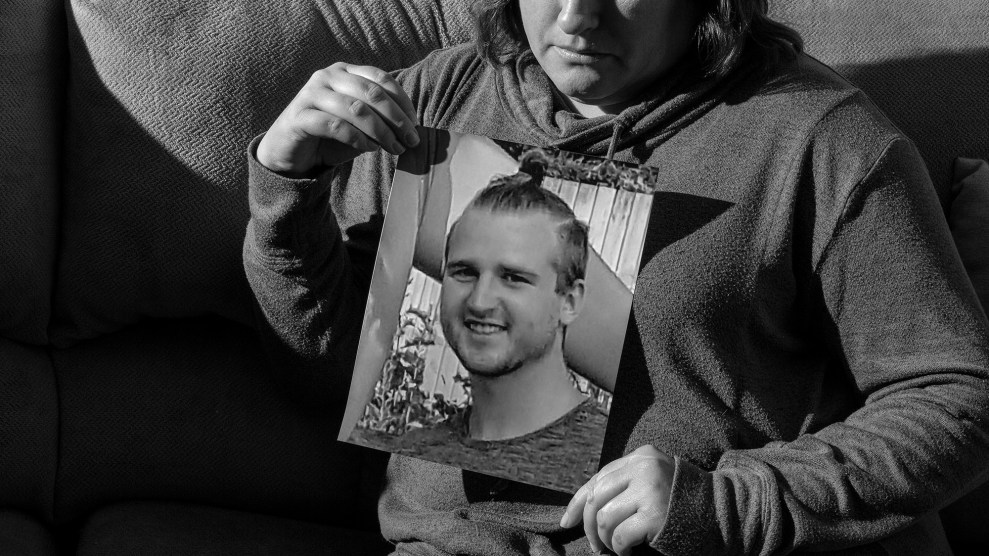

Another crucial component of this model is comprehensive case management. In many towns, the co-responders arrive on the scene not to treat an emergency, but to talk, listen, and offer a direct link to treatment. They make a point to follow up within two days of an emergency. In one such example, Larsen tells me about an incident from earlier this year, when a woman who asked to be identified by the initials D.D. overdosed. As soon as one of Larsen’s colleagues in Framingham learned about the call, the co-responder dispatched a recovery coach from Advocates named Billy Parks to meet D.D. at the hospital. D.D. tells me seeing Parks, who shared his own experience with substance use, at her bedside helped her see that there was a way out of her situation. “I wasn’t being shamed,” she says, “for what had happened.” When we spoke, D.D. had been in recovery for one month.

Despite the uptick in interest, there’s little uniformity to these types of law-enforcement initiatives, making it difficult to have a comprehensive understanding of how the police–social worker model has changed conditions on the ground. But what information is available suggests outcomes in Massachusetts are promising. Data from Advocates shows that since 2003, up to 88 percent of people with behavioral health conditions avoided arrest, resulting in a total estimated cost savings of as much as $4.9 million for the state. What’s more, recent data shows that deaths from opioid overdoses appear to be falling across Massachusetts—though that’s likely due to not just the shift in how law enforcement responds, but also work from social service agencies and community peer-to-peer support groups.

Outside of Massachusetts, dozens of cities and communities have implemented similar police-mental health collaborations. Data suggests these initiatives often succeed at jail diversion—moving nonviolent offenders away from traditional criminal justice pathways and into treatment systems—but the overall effectiveness in reducing drug overdoses has not yet been rigorously tested.

Beyond the numbers, there’s another unexpected benefit of the Massachusetts model. By putting civilians inside police stations and cruisers, Abbott says she’s watched the culture of police change. “I can say our department officers are friendlier, they are kinder, and they are more compassionate on these kinds of calls. I feel pretty good about that,” she says. Abbott also notes a subtle shift in how officers tend to discuss mental health with each other. Framingham deputy police Chief Lester Baker says police now convene peer-to-peer “roundtables” after on-duty calls that are particularly traumatic or triggering. “Nobody wants to say, ‘I need help.’” Baker says. “Now, we’re putting you in a situation where it’s not help, but we’re all just going to have a conversation.”

As we continue to ride around Framingham on that Friday night in April, it’s clear Larsen is just one part of a network of support—a system that can sometimes still seem like it’s designed to fail people. It’s a little before 5 p.m., and Larsen is busy trying to reach clinicians before they clock out for a long weekend. She finally gets through to a colleague to ask if a client’s behavior is typical. (“For you, is this off-baseline?”) Later, Larsen follows up with a hospital where she and officer Goncalves dropped off a psych emergency services patient earlier in the day. After pulling up some records on her laptop, she tells us that the man seems to have run-ins with police every year around his birthday. He needs a bed at an in-patient facility.

About a half hour after checking on the man nodding out on the sidewalk, Goncalves’ radio beeps again. Dispatch reports that someone else has passed out on the sidewalk. Goncalves circles around through the center of town. A commanding officer gets on the radio: “Is Danielle available?” “Roger,” Goncalves says, flipping on his lights and siren.