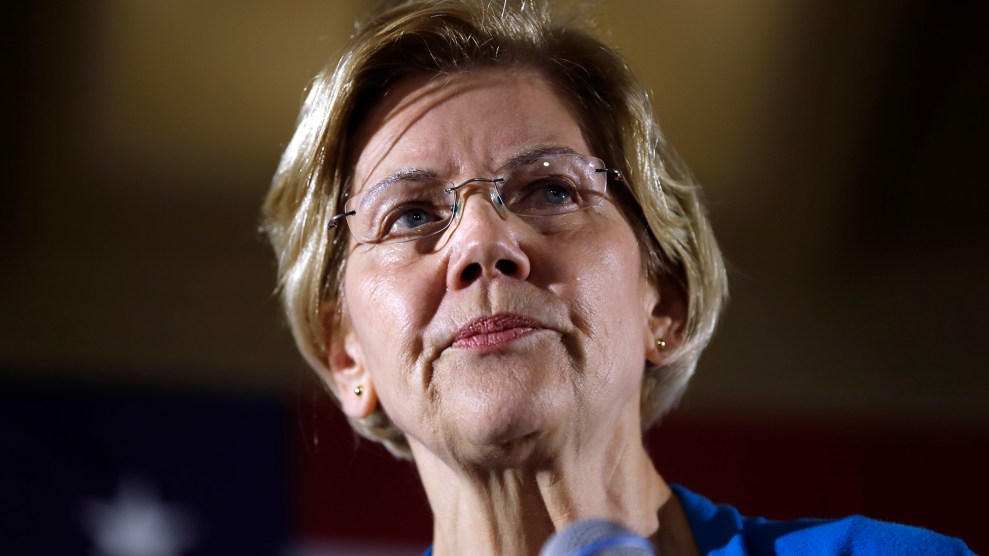

Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren at the Democratic Presidential Debate in Detroit in July 2019.Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

On Tuesday, Sen. Elizabeth Warren unveiled her plan to reform the criminal justice system, just two days after Sen. Bernie Sanders revealed his own. Both presidential candidates are proposing similar changes that would have been unimaginable several years ago—banning private prisons, and ending policies like mandatory minimum sentences, cash bail, solitary confinement, and the death penalty. But these measures aren’t necessarily the most radical things about their approach to criminal justice reform.

Other Democratic candidates, including some who hew more closely to the center, have recommended these changes, signaling how far the party has come in its approach to punishment. Former Vice President Joe Biden, facing criticism for the tough-on-crime legislation he wrote as a senator in the 1990s, put out a plan in July that would repeal mandatory minimum sentences, eliminate the death penalty, and end the federal government’s use of private prisons. South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, like Sanders, wants to cut the incarcerated population in half. Sen. Cory Booker has introduced legislation to reform federal sentencing policies, and Sens. Kamala Harris and Amy Klobuchar, both former prosecutors who have faced criticism for their histories in criminal justice, have crafted thoughtful proposals to better fund public defenders and help more prisoners commute their sentences.

But Warren’s and Sanders’ plans are more comprehensive, and not just because they are longer (though they are certainly more fleshed out than the plans put forward by Biden or Buttigieg, or the platforms shared by other candidates on their websites). What really sets Warren and Sanders apart is the extent to which they rethink what it takes to keep people safe; their plans say real public safety can be achieved only through less focus on law enforcement and more on tackling underlying drivers of crime like underfunded schools, inadequate housing, and poor mental health care, especially for communities of color. “It’s not enough merely to reform our sentencing guidelines or improve police-community relations,” Warren writes toward the top of her plan. “We need to address the deeper structural problems that give rise to crime, such as joblessness, income inequality, lack of education, and untreated substance abuse,” Sanders writes in his.

“These [plans] are leaps and bounds beyond anything I’ve seen proposed at the federal level, by Obama or anyone,” says Kevin Ring, the president of an organization called FAMM that represents families with incarcerated loved ones. He says other candidates have touched on these ideas, but with less detail. “They are definitely wrapping in a larger package of how there are some communities hit harder, and we’ve got to help these communities before they get to prison.” Sanders includes a section in his plan, for example, that recommends passing a $15 minimum wage, providing transportation benefits to and from doctors’ visits, enacting paid family leave, and offering federal grants to entrepreneurs of color, among other things.

Warren, for her part, begins her plan by lamenting that at least 14 million students go to schools with a police officer but no counselor, social worker, psychologist, or nurse, something that contributes to suspensions and expulsions. Sanders points out that black students are about four times likelier to be suspended than white students, making them more likely to fall behind or drop out and become ensnared in the criminal justice system. Both say they would funnel more money toward school mental health personnel and counselors.

To be sure, their framing of public safety as a product of widespread access to essential services is refreshing to some progressive groups who have been pushing for criminal justice reform for decades. “What I find most encouraging about [Warren’s] plan is that she starts off talking about crime and safety not in criminal justice terms, but more so in ‘How do we build strong families and communities?’” says Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project, an advocacy group in Washington, DC, that pushes for alternatives to incarceration.

Both, too, support programs in Oakland, New York, and Boston that work to prevent shootings by connecting people who are most at risk for violence to essential services like job training and life coaching. Last year, a study by Northeastern University found that Operation Ceasefire, as the program is called in Oakland, was responsible for a 30 percent drop in violence there.

Warren and Sanders also each point to Medicare for All as a key component of public safety and criminal justice reform. In 44 states, jails or prisons care for more mentally ill people than hospitals, according to the Cook County Sheriff’s Office, which runs a jail in Chicago that is one of the country’s largest mental health care providers. “[I]nstead of shuttling people into a system not built to meet their needs, we should invest in preventing people from reaching those crisis points in the first place,” Warren writes. “Medicare for All will provide continuous access to critical mental health care services, decreasing the likelihood that the police will be called as a matter of last resort.” Both senators also support legalizing safe injection sites for people who use drugs.

Warren’s and Sanders’ plans are also remarkable for the depth with which they tackle problems with sentencing, prosecution, prison conditions, policing, reentry, and many other aspects of the criminal justice system. Sanders proposes restoring voting rights to all incarcerated people and ending prison gerrymandering, a common practice whereby states count incarcerated people as residents of the town where their prison is located, rather than where they are from, reducing representation in their communities. Warren explains the need to appoint more diverse judges to the federal bench, which has long been dominated by white men. Both suggest changes that would affect everything from the presidential clemency process to funding for public defenders.

“What’s very intriguing, even going beyond just the two of them, is how the landscape has shifted, quite dramatically in recent years,” says Mauer. “Obama, to his credit, always talked about communities and inequality and racial issues, but he didn’t take a hard line saying, ‘We have to repeal the death penalty, we have to repeal mandatory sentencing, end the drug war,’ all of that. Much of that was more nuanced than the proposals we are seeing now, again even from some of the more mainstream people.

“There’s generally an assumption among the Democrats that it’s time to end mass incarceration,” he adds. “That is a real breath of fresh air.”