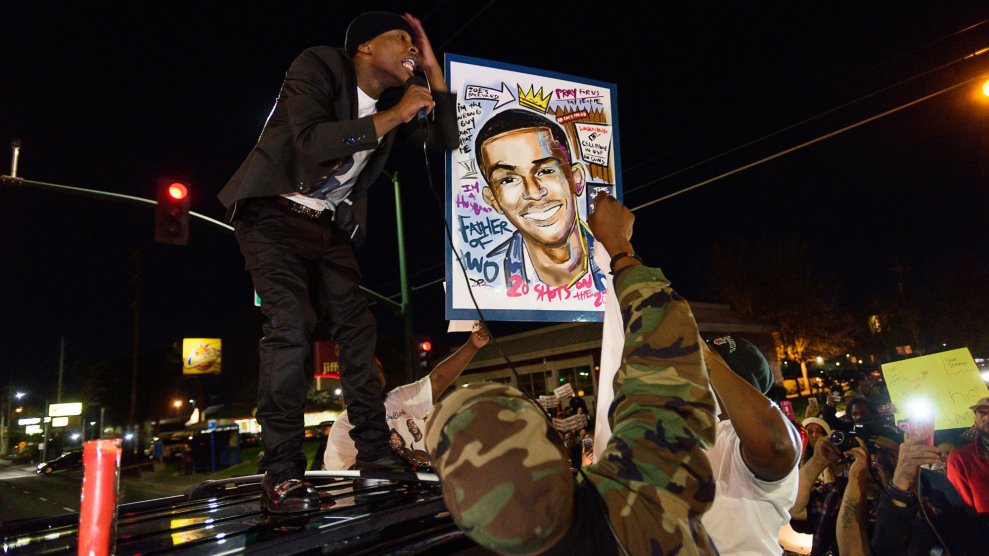

Demonstrators protest the police killing of Stephon Clark in New York City on March 28.Erik Mcgregor/Pacific Press via ZUMA Wire

Ben Crump, the civil rights attorney representing the family of Stephon Clark, tells Mother Jones he believes the Sacramento police officers who shot Clark, unarmed in his grandmother’s backyard, “absolutely” violated the department’s policies on use of force, specifically one requiring them to use de-escalation tactics. One major error, he says, was when they left a position of cover behind the wall of the house and moved into the yard to engage Clark in the open.

Crump made the comments while leaving a press conference after Clark’s funeral Thursday morning in Sacramento.

“If they would have offered a less intrusive measure, a less lethal way of using force, Stephon Clark would be here today,” Crump said. “And it would have been one of the things that was within their policies.”

Asked what remaining behind the wall would have allowed officers to do differently, Crump responded: “They could have gave commands, gave him time to comply.” He added: “They did not have to shoot him.”

The Sacramento Police Department’s use of force policy calls on officers to attempt to de-escalate a situation “where it may be accomplished without increasing the risk of harm to officers or others.” Such tactics, according to the policy, can include “gathering information about the incident; assessing risks; gathering resources (personnel and equipment); using time, distance, cover; using crisis intervention techniques; and communicating and coordinating a response.”

Crump said he believes his investigation of the shooting will prove that the two officers who shot at Clark 20 times violated that requirement.

His analysis of officers’ conduct dovetails another one detailed to Mother Jones by prominent San Francisco Bay Area civil rights attorney John Burris. Burris helped to craft the language in several of the Sacramento Police Department’s policies governing officers’ conduct during use of force incidents. He told me he believes the officers who shot Clark violated at least three department rules when they engaged with Clark. Among the rules violated, Burris said, was a requirement that officers “continuously reassess the perceived threat” to determine what level of force is appropriate. Officers could—and should—have done that from their initial position of cover behind a wall of the house, Burris said.

“If you’re in a position of cover, you’re in a position to assess better, you can give commands and take the time to see whether or not there’s an effort to comply,” Burris said. “But if you don’t, and you feel that you’re exposed because you’ve broken cover, then you may react more quickly and [be] quicker [to] use deadly force than you would have if you had been in a position of cover.”