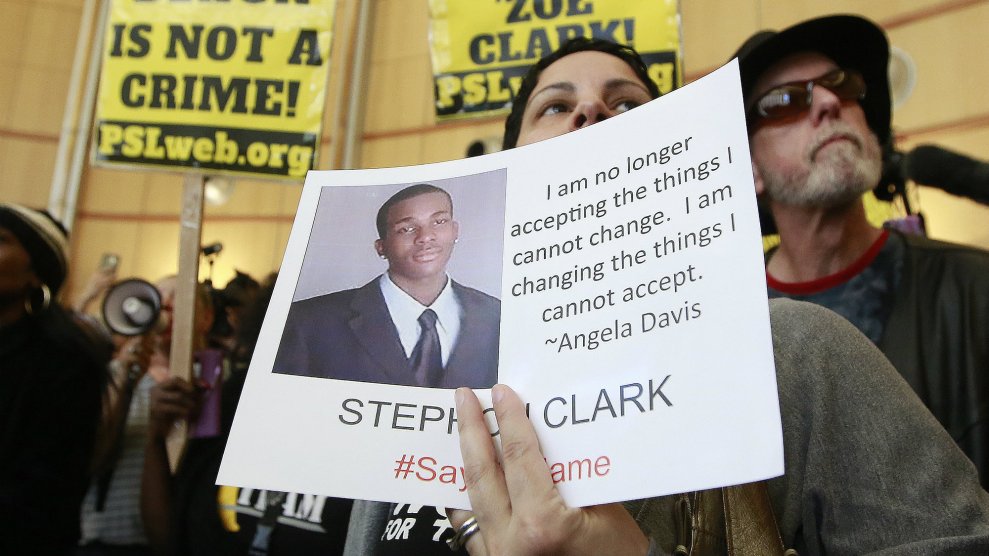

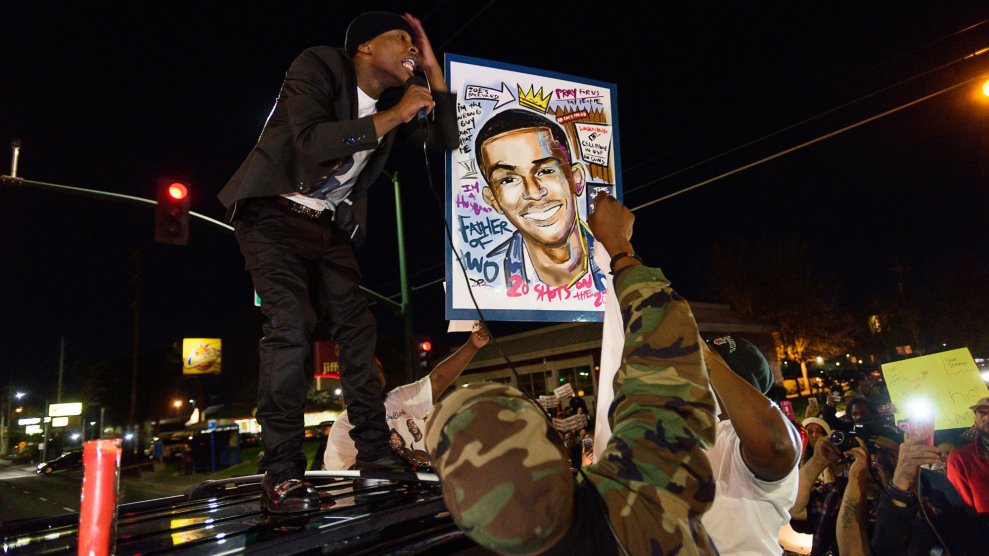

Stevante Clark, the brother of Stephon Clark, holds a sign depicting his brother at protest on March 23.Paul Kitagaki/ZUMA Press

The Sacramento Police Department officers who fatally shot unarmed 23-year-old Stephon Clark in his grandparents’ backyard earlier this month may have violated several department policies governing conduct during police shootings of civilians, John Burris, a prominent San Francisco Bay Area civil rights attorney, tells Mother Jones.

Burris was involved in drafting the Sacramento City Council mandate that would inform changes made last year to the Sacramento PD’s polices on use of force after he represented the family of Joseph Mann, a 51-year-old who was shot by local police officers in July 2016. Cell phone and police dash cam videos of the incident showed police shoot Mann 14 times times after first trying, but failing to hit him with their car. Relatives of Mann, who was homeless, have said he struggled with mental health issues.

The case prompted changes to department rules on when officers can discharge their firearms and how officers should offer aid to injured suspects. Sacramento’s City Council also subsequently required the police department to release police body camera footage of incidents involving the use of lethal force within 30 days of the incident.

Now, with the shooting of Clark, the departments rules on when officers can use force will be revisited again, Sacramento Police Chief Daniel Hahn said at a Tuesday press conference. The shooting occurred, police officials have said, after Clark extended his arms toward the two officers on site holding an item that they believed to be a gun. Officers ultimately found only a phone near Clark’s body, and no gun was recovered. In the two body camera videos released four days after the shooting, Clark can’t be seen until moments before the shooting. Before he’s visible, an officer can be heard commanding him to stop and show his hands as they enter the house’s backyard. Moments later, another officer yells, “Show me your hands—gun!,” and both officers take cover behind a wall of the house. An officer again yells, “Show me your hands—gun, gun, gun!,” and then a flurry of shots ring out. Just before officers begin firing, Clark can briefly be seen standing on a patio area toward the back of the yard.

Burris told me he believes the officers involved, who both fired 10 shots at Clark, according to the Sacramento Police Department, specifically violated three key policies governing conduct in police shooting incidents:

Officers did not warn Clark that they intended to use lethal force before shooting

A Sacramento PD policy requires officers to give clear warning “when feasible” that they intend to shoot a suspect before doing so. But Burris notes that officers only commanded Clark to show his hands—an insufficient precursor to firing their weapons at him. “If you think a person is creating danger, potential danger, you want to tell them ‘Show me your hands. Stop. If you don’t, I’m going to shoot,’” Burris says. “You have to give the warning and then you have to give him time to comply.” He adds, “There’s nothing about [the video] that suggests they didn’t have time to do that.”

Officers initially took a position of cover behind a wall of the house, Burris notes, but then moved out from behind the wall into the yard, at which point they begin shooting at Clark. Had officers remained behind the wall for a longer time, he says, they could have remained in a protective position and also warned Clark that they were going to shoot, especially given the distance between Clark and the officers.

They did not appropriately assess what kind of threat Clark posed

Officers may also have violated a policy requiring them to “continuously re-assess the perceived threat” to determine what level of force is necessary, Burris says. The key here, he notes, is that officers in this situation had initially taken cover behind the house. They then moved out into the yard where they made themselves more exposed to what they apparently believed was a man with a gun. That decision to move from behind the wall created a circumstance that likely lessened their ability to assess what kind of threat Clark actually posed, as well as how many shots they needed to fire. It also increased the likelihood that they would need to shoot, had Clark actually been armed with a gun, Burris says. “Time, distance, and space are critical aspects in a police evaluation. If you’re in a position of cover, you’re in a position to assess better, you can give commands and take the time to see whether or not there’s an effort to comply,” he says. “But if you don’t, and you feel that you’re exposed because you’ve broken cover, then you may react more quickly and [be] quicker [to] use deadly force than you would have if you had been in a position of cover.”

Each officer fired 10 shots at Clark, for a total of 20. It’s unclear how many times Clark was hit, but Burris says the shooting is a clear example of an excessive use of force. “It looked like each officer emptied their guns, and was going to reload,” Burris says. One officer did, in fact, reload his weapon. “That to me was pretty shocking, particularly when you have not received any fire back.”

They didn’t render first aid quickly enough

Officers were too slow to give Clark first aid after the shooting, Burris says—a potential violation of a department mandate that they render first aid “when it can be done safely.” Officers waited approximately five minutes after they stopped shooting before allowing a medic to treat Clark, a decision Burris says flouts the department’s first aid mandate given how obvious it would have been that Clark needed medical attention. After back-up arrives at the scene, officers can be heard in the videos expressing that they want to be sure Clark is not still a threat before approaching him. But Burris says such a concern was unreasonable at that point. “Given the number of shots that were fired, and there was no response to those [shots], that should have lead them to believe that he was probably disabled, and they should have went and approached the situation more expeditiously than they did,” Burris says.

In a remarkable moment, one of the officers who shot Clark can be heard telling another officer, “Let’s hit him with a baton,” in order to determine whether Clark was disabled. Before that, another officer can be heard saying that an officer should bring a non-lethal weapon “just in case he’s pretending.” At this point, Clark had already been on the ground for several minutes. “I actually have never heard or seen anything like that occur in the past ever, and I’ve been involved in well over 50 police shooting cases in my career,” Burris says.

This article has been updated to reflect changes to the Mother Jones style guide.