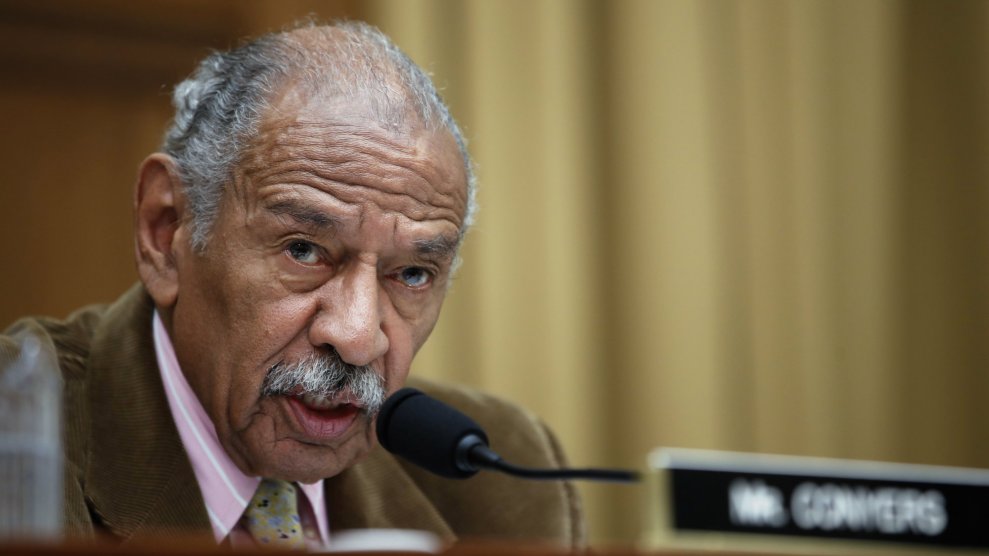

Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., speaks during a hearing of the House Judiciary subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, Homeland Security, and Investigations, on Capitol Hill in Washington on April 4, 2017.Alex Brandon/AP

Last month’s torch-lit white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, a response to the planned removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee from a public park, kickstarted a national dialogue about how communities should address this nation’s centuries-long history of violence and discrimination against African Americans. Democratic politicians and others, pushing back against the old arguments about maintaining our “heritage,” have called for the removal of additional Confederate statues and monuments from public spaces. Black people, they say, should no longer be faced with laudatory memorials to people who fought to keep their ancestors enslaved.

Among those calling for the removal of what President Donald Trump called “beautiful statues and monuments” was 88-year-old John Conyers of Michigan, the nation’s longest serving congressman. For nearly three decades, in fact, Conyers has been arguing that there is much more the government can and should be doing to atone.

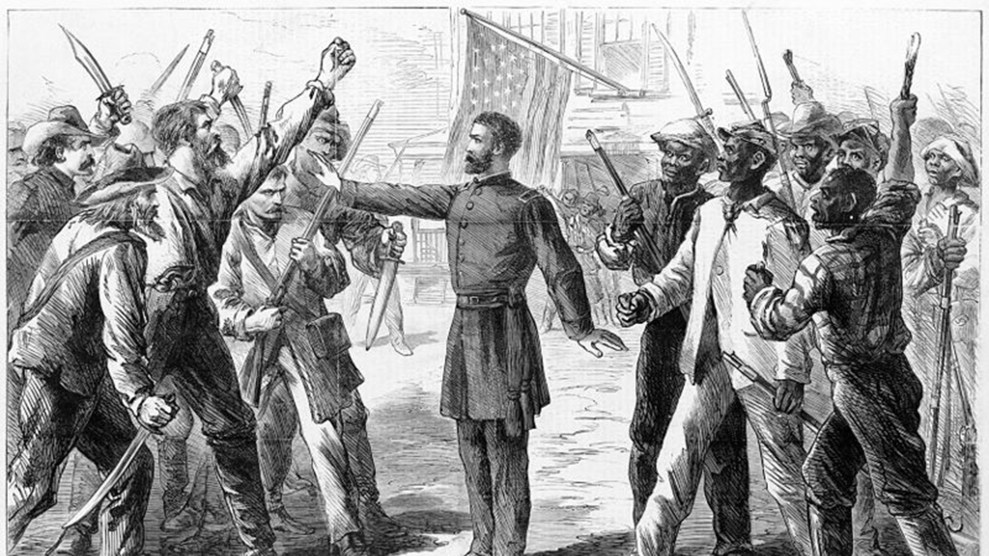

Every year since 1989, Conyers has introduced House Resolution 40—a reference to the famous order by Union Army Gen. William Sherman that 40 acres of land, largely confiscated from former Confederate slaveholders, should be set aside for the families of former slaves. The bill would create a congressional commission to study the modern legacy of slavery and Jim Crow and propose recommendations—possibly including reparations for black Americans. In all that time, HR 40 has never made it out of committee, but Conyers intends to keep trying. “Slavery is a drawback that people don’t want to have to remember,” he told me. But “the labor and the work product of those that were enslaved goes into the trillions of dollars.”

“Restoring justice requires that we address this thing,” he added.

The 13-member commission Conyers’ bill calls for would spend a year reviewing the existing research on the scope and lasting impact of African American enslavement and Jim Crow-era discrimination, and ponder what the government might do to help remedy the problem—including the form that any compensation might take, how much would be appropriate, and who should receive it. Although it does not authorize actual reparations payouts, it does allocate $12 million for the operation of the commission, which would have authority to compel federal agencies to hand over relevant records and documents. The panel also would look at federal policies that harm African Americans and suggest changes—as well as advise Congress on how to educate the public about the findings.

Conyers reintroduced HR 40 (for the 28th time) in January. Most of the bill’s 32 co-sponsors are black and all are Democrats. In February, Conyers hosted a panel with speakers from various reparations advocacy groups to promote HR40 on Capitol Hill. He’s holding a similar panel Friday as part of the Congressional Black Caucus’ Annual Legislative Conference.

“What we want to do is have people more appropriately understand the relationship between [historical discrimination and] the racial tensions that are still quite evident,” Conyers said. “This legislation will make people see this [connection] and become more supportive of the notion that all of us have a responsibility to do something to make things better.”

The reparations conversation has been reenergized thanks in part to fresh research and moves by some universities and companies to make amends for their own complicity in the slave trade. Last year, for instance, Georgetown announced it would grant admissions preference to the descendants of 272 slaves the university sold in 1838 to keep its doors open.

But perhaps the most significant addition to the debate has been “The Case for Reparations,” Ta-Nehisi Coates’ 2014 Atlantic cover story, which characterized the United States as a “kleptocracy” that enriched white Americans by means of nearly 400 years of “plunder” of black communities. That thesis is supported by new research showing that white households, on average, are worth nearly 20 times more than black household—and that it would take 228 years for the average black household to catch up. (Coates stirred things up again this month with an Atlantic essay arguing that Donald Trump’s whiteness and his embrace of white supremacy are precisely why he was elected president.)

The topic has also popped up in political campaigns. In February 2016, racial justice advocates pressed former Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders on why he doesn’t support reparations. A coalition of groups affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement also has adopted reparations as part of its own political platform.

“The inequality that exists is only there as a result of the crimes that were committed against our ancestors,” says Kamm Howard, a representative for the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, an advocacy group. Howard will speak on Conyers’ panel on Friday. “That inequality cannot be eliminated without massive resources targeted toward African [American] people. Does it have to take a check? No. But can it be done within the construct of the national budget?” Absolutely, Howard says.

Americans as a whole oppose slavery reparations—nearly 7 in 10, according to a 2016 poll. Significantly, more than 80 percent of white respondents were against reparations—only 15 percent were for them. Black respondents supported reparations by a 58/35 margin. Hispanics were split.

Given this, it’s not surprising that Conyer’s bill has never gained much traction. In 2007, the House Judiciary Committee, which Conyers then chaired, held a hearing on the bill—but as usual HR 40 didn’t make it out of committee. The bill’s momentum peaked in 2009, when Democrats controlled both the House and the Senate, Howard says. Reparations advocates were confident they could get most of the Congressional Black Caucus, and many of the nonblack representatives who endorsed the House’s official apology for slavery in 2008, to co-sponsor the bill. But that momentum was stunted by a shift in focus to passing Obamacare.

There are historical precedents for reparations in America. In 1988, Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act, which allocated more than $2 billion for survivors of the internment camps where Japanese Americans were imprisoned during World War II. (Conyers first introduced HR40 the following year.) In 1990, the government began sending $20,000 checks to each of the more than 100,000 surviving detainees. The federal government has also spent billions of dollars settling lawsuits with some Native American and Alaskan native tribes related to theft of tribal land and resources. In 2010, The Obama administration agreed to pay nearly $1.3 billion to more than 70,000 black farmers to settle lawsuits over discrimination by the Department of Agriculture’s loan program. But lawsuits seeking reparations for slavery have been unsuccessful.

Last September, the UN urged the US government to pay reparations to African Americans for a history of “enslavement, racial subordination and segregation, [and] racial terrorism.” There’s not much research available on what might be an appropriate figure. A 2015 study by a researcher at the University of Connecticut estimates the lost wages of black slaves during the 89 years from the country’s founding to the end of the Civil War add up to somewhere between $6 trillion and $14 trillion. (Last year, the federal government spent less than $4 trillion on all government expenses and programs combined.) “That’s one of the major contentions that people have—that it would be too expensive and they don’t know where it would begin,” says Howard. But “that’s why HR40 is so important. It would lay out those types of things.”

Many reparations advocates have proposed pumping massive amounts of money into federal programs aimed at black economic development over a period of decades. But the battle isn’t just about money, Howard says: “For us it’s about repair: repair of our personhood, repair of our families, repair of our communities, repair of our educational livelihood.”

The latest HR 40 co-sponsor to sign on, earlier this month, was Ro Khanna, a Democrat representing parts of Silicon Valley. Reparations for African Americans “has to be a moral priority and economic priority,” Khanna told me. “The discrimination and injustices against the African American community is in a league of its own,” and “there are structural and historical reasons” why black people haven’t had the same opportunities as white people.

Conyers thinks many of his colleagues are afraid of having the slavery conversation. “It’s kind of embarrassing to admit that things went on like this for so long,” he told me. “So there’s nobody anxious to bring it up.” Howard makes the same point. “All public institutions in America have benefited from enslavement,” he says. “I don’t think they’re ready to face the complicity of all America.”

“The American ethos is one that is anti-black,” Howard adds. “I don’t think that they’re ready to deal with that.”