menonsstocks/Getty

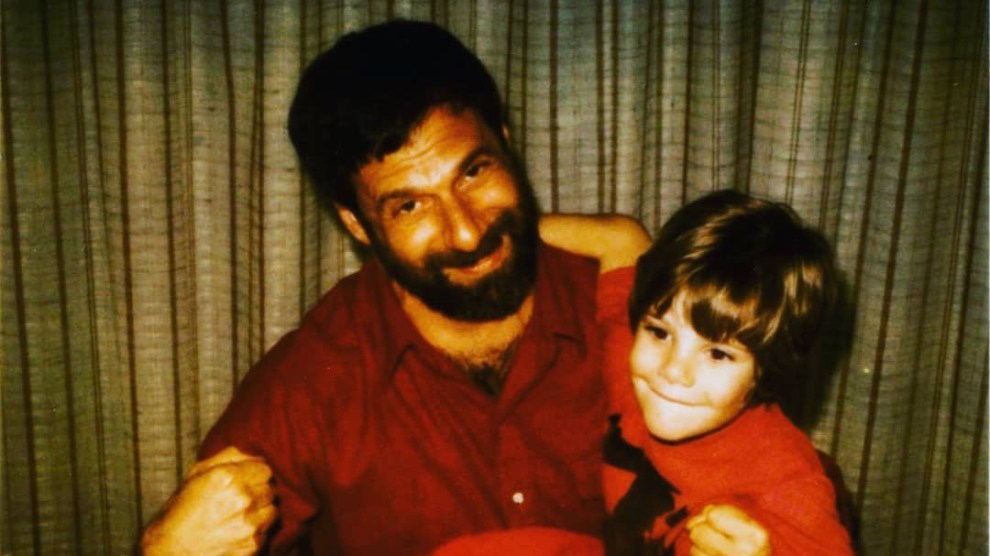

Susan Farrell was 74 when she died last month at the Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility in Michigan. Ailing and often in a wheelchair, she succumbed to COVID-19 after spending more than 30 years behind bars for allegedly murdering a husband who, she said, had abused her. Farrell, who maintained her innocence until the end, had fought to have her life sentence commuted, but her request was denied in 2018 by former Gov. Rick Snyder.

In her final years, Farrell was “frail and disabled by years of sexual and physical abuse,” according to her clemency application. She had endured surgeries to repair the damage the violence wreaked on her body. Her poor health likely made her more susceptible to the virus.

“Had [Snyder] commuted Susan’s sentence, she would likely be alive today, in my opinion,” says Carol Jacobsen, director of the Michigan Women’s Justice and Clemency Project, which works to free female prisoners convicted of murder for defending themselves against abusers.

Farrell is far from the only woman to die behind bars from the disease. There have been three other coronavirus deaths and more than 300 confirmed cases in the prison where she passed away. Michigan has some of the highest numbers of prisoner fatalities from COVID-19, according to the Marshall Project. But across the country, prisons and jails have become hot spots for infection. More than 450 prisoners have died so far, according to the UCLA Law School’s COVID-19 Behind Bars Data Project.

Government officials have responded by releasing thousands of nonviolent offenders, especially elderly prisoners and those with underlying medical conditions. Typical state prisons have reduced their populations by about 5 percent during the pandemic, and jails by more than 30 percent, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. High-profile people convicted of crimes, such as former Stormy Daniels attorney Michael Avenatti and former Trump aides Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort, have won release from federal custody due to the virus.

But the focus on nonviolent offenders has left behind a particularly vulnerable group of prisoners—women like Farrell who were convicted of murdering partners they say were abusive.

As of 2017, about 99,000 women were incarcerated in state prisons nationwide, and another 114,000 were locked in jails. The majority of female prisoners were previously abused, but there’s no precise data on the number of women who have been incarcerated for killing abusive partners, family members, or traffickers. One study, conducted by the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, found that 67 percent of women sent to prison in that state in 2005 for murdering someone close to them had been abused by the person they killed.

Many of these women are older and suffer from serious medical conditions related to years of abuse, says Sue Osthoff, director of the National Clearinghouse for the Defense of Battered Women. That means they’re at risk for severe, even deadly, complications from COVID-19.

“We really have to think differently about people who have done one terrible thing in their past,” Osthoff says. “We can’t sentence those people to death—we just can’t do that—and we are.”

At least four domestic violence survivors who say they fought back against abusers sought release from prison last month but had their requests denied by a Midwestern parole board, according to an attorney involved in some of the cases. The attorney requested anonymity to protect their clients’ privacy and prevent retribution. The board said in its denial letters that parole reconsideration requests had to be based on “significant new information…not considered at the time of the hearing.” The threat posed by the coronavirus was apparently not considered significant enough.

In New York, at least 10 survivors of family violence who say they fought back against abusers have asked for clemency during the pandemic, according to a lawyer involved in their cases. One of those petitions describes the survivor as disabled due to injuries resulting from years of physical abuse. Six others also have underlying health conditions, potentially subjecting them to greater risks from COVID-19, the lawyer said. So far, none of the petitioners have been released.

“No matter what the situation was, they are labeled as a murderer, so nobody wants them to get out,” says Tiffanny Smith, an attorney at the Ohio Justice and Policy Center who works with incarcerated survivors of domestic violence.

But reports suggest that survivors who are imprisoned for defending themselves against abusers rarely reoffend and usually had no criminal history prior to the offense against their abusers. For that reason, Smith argues, authorities should look at the actual risk that a prisoner would pose if she were released—not just the name of the crime she was convicted of.

When women use force against their abusers, it is frequently motivated by self-defense, the need to escape abuse, or the need to reclaim a sense of self, according to a 2019 analysis in the journal Violence Against Women. But women who fight back often end up punished for it. Self-defense laws generally require that the threat of death or serious harm be imminent, that the fear of harm be reasonable, and that the use of force be proportional.

Myths that portray domestic violence victims as “weak, meek,” and “passive” can undermine a self-defense claim by creating credibility problems in the eyes of the courts for women who don’t fit the mold of a stereotypical victim, says Leigh Goodmark, a law professor at the University of Maryland and one of the authors of the Violence Against Women paper. These stereotypes particularly affect African American women, trans women, and lesbians, she notes.

“When you kill your partner or when you assault your partner, you have done something that flies in the face of that narrative,” she says.

That’s what happened to Tracy Van Sickle, who was found guilty of murder in 1992 and sentenced to 15-years-to-life before having her conviction overturned on appeal. Two years later, a judge in a second trial found her guilty of voluntary manslaughter. In both cases, her arguments of self-defense were rejected, despite the fact that she presented evidence she’d been abused by the man she killed—abuse that, she testified, included threats to kill her and her family members. After serving 12 years, she was finally freed by Ohio’s parole board, which noted the “horrible sexual, physical, mental and psychological abuse” she’d experienced.

As a free woman, Van Sickle thinks of the abuse survivors who are still in prison, now living with the threat of COVID-19.

“I can’t imagine how afraid I would be to be in there,” she says. “I’m scared enough out here.”