JPecha/Getty Images

A man on Texas’ death row has what seems like a fairly simple request: he wants his lawyers to do an investigation into his background—something his counsel says he’s legally entitled to before being put to death.

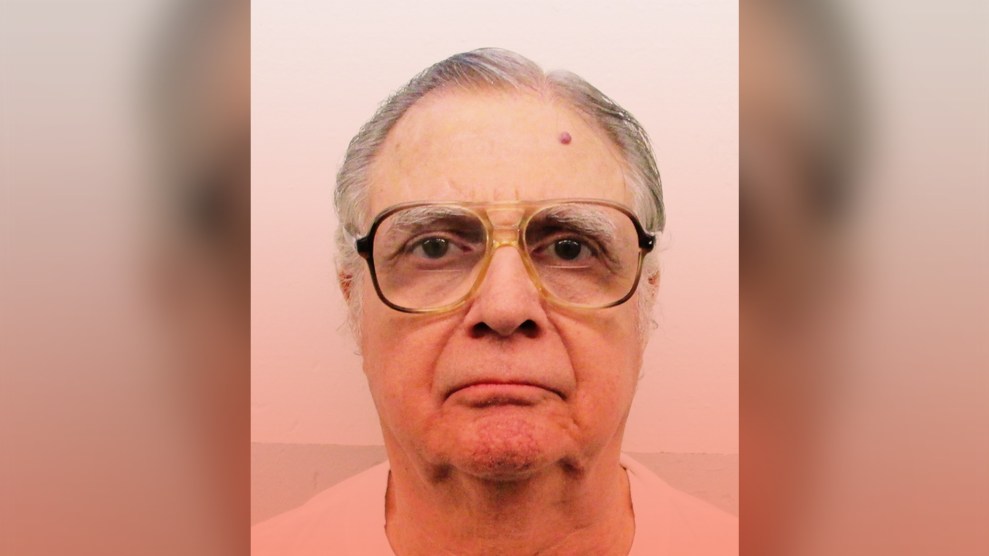

Carlos Ayestas, a mentally ill undocumented immigrant from Honduras, is arguing that a series of missteps by his trial lawyers led him to be sentenced to death in 1997 at the age of 28, without the jury hearing any mitigating evidence that could spare his life. Even after appealing to a federal court in 2009, there has been no investigation into his personal history, nor have any of the courts given weight to his mental health, and therefore there has been no way bring up the kind of personal details that could spare Ayestas his sentence.

Now, in his last chance for justice, the US Supreme Court will hear Ayestas’ case this fall. According to the brief filed in June, the defendant will ask the high court to enforce the statutes that are supposed to protect poor defendants facing the death penalty. Specifically under consideration are the state resources that should be made available to pay for experts or investigators, but have been denied throughout Ayestas’ appeals process.

In 1995, Ayestas, who’d come to the United States seven years prior, and two accomplices fatally strangled 67-year-old Santiaga Paneque in the course of a robbery in her home in Harris County, Texas. Police quickly identified the perpetrators but did not yet have them in their custody when, two weeks after the crime, Harris County Assistant District Attorney Kelly Siegler wrote a memo recommending that Ayestas receive the death penalty based on two aggravating factors: one, because the victim was elderly and murdered in her own home and, two, because Ayestas “is not a citizen.”

“It’s intolerable that a person’s nationality would play a role in seeking the death penalty,” says Sheri Johnson, one of Ayestas’ current lawyers. “In Texas, there are at least a handful of [undocumented people on death row].” (Foreign nationals on death row have a right to consular notice, but they don’t always receive it, Johnson explains. Right now she says that this issue is on hold while the team litigates the funding issue.)

Lawyers appointed to indigent defendants are frequently undertrained, underpaid, and overworked, placing defendants at an immediate disadvantage. But, making matters worse, Harris County is notorious for its poor handling of death penalty cases for indigent defendants. According to a 2016 report from the Fair Punishment Project that focused on the counties still applying the death penalty, Harris County was plagued by subpar lawyering, overzealous prosecutors, and racial bias—all of which disproportionately impact poor defendants. And in 2015, a state court found that Siegler herself committed 36 instances of misconduct in just one murder case.

Two days after the Siegler wrote the memo, Ayestas was captured in Kenner, Louisiana, and charged with capital murder.

For the trial, the state court appointed two lawyers, Diana Olvera and Connie Williams, to represent Ayestas. Olvera and Williams then asked the state court to appoint an investigator to look into Ayestas’ background, a routine part of capital murder trials. But the investigator, John Castillo, didn’t actually start his investigation until 15 months after it was assigned—and just one month before jury selection was slated to start.

As part of his investigation, Castillo had Ayestas fill out a questionnaire. His responses, according to his current lawyers, indicated that he suffered multiple head traumas, had been drinking since he was a teenager, regularly used cocaine, and was under the influence of the drug and alcohol on the day he murdered Paneque. But, according to Johnson, his lawyers did little with that information at trial.

Ayestas’ trial lawyers did not look into his past either, which would also be typical in capital trials to supplement the work of the state-appointed investigator. They did not meet with any friends or family or with anyone who knew him in any of the places that he lived as an adult. Although Olvera says that Ayestas originally asked not to have his family contacted, about two weeks before jury selection began in June 1997, they reached out to his family members in Honduras and asked them to come testify at trial. Ayestas’ mother, though, believed she was going to receive a letter from her son’s lawyers that she could use to obtain a visa. It’s unclear whether there was miscommunication about the letter, but no such letter arrived; Ayestas’ family members’ visas were denied and no one showed up to his trial.

The guilt phase of the trial began in July 1997 and lasted two days. The defense lawyers presented no witnesses and Ayestas was quickly convicted.

The following sentencing phase, during which jurors were tasked with deciding if Ayestas should be put to death, was even shorter. Prosecutors presented jurors with evidence of the defendant’s past criminal offenses and testimony from Paneque’s son. Meanwhile, Ayestas’ lawyers again presented no witnesses. Instead, they offered the jury three letters from a prison instructor who was teaching Ayestas English.

“His lawyers presented virtually no mitigation evidence at all,” says Johnson. “The jury had no sense of anything that could weigh against death.”

The sentencing phase lasted less than a day. It took jurors 12 minutes to deliberate and sentence Ayestas to death.

During his appeals process, Ayestas’ court-appointed lawyer continued to leave information on his substance abuse buried and to ignore his mental health issues.

If anyone had done a mental health evaluation, they likely would have discovered that the defendant was suffering from schizophrenia. The onset of the disease is typically in one’s early-to-mid twenties, around the time Ayestas committed the murder. While his application appealing to the state court was pending in 2003, Ayestas suffered a serious psychotic episode and was subsequently diagnosed with the illness.

It was not until 2009, when his appeal was in federal court, did his newly-appointed lawyers finally sought to do a background investigation into his mental health and substance abuse issues. But the court denied the funds the team needed to do a thorough investigation.

The Criminal Justice Act provides indigent defendants with a right to representation and any other services the accused might need to prove his or her case in federal court. The law also comes with a capital provision which allows defendants facing the death penalty access to higher-quality lawyers and investigators and experts that are “reasonably necessary” in the post-conviction phase. Ayestas’ lawyers argue that the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which was next in line to hear Ayestas’ case, also applies a “substantial need” test that requires a “higher showing” than the “reasonably necessary” requirements of the federal law.

So after Ayestas appealed to the Fifth Circuit, it ruled in March 2016 that he didn’t have a “substantial need” because he should’ve been able to prove he didn’t have adequate counsel at the time he requested assistance. The court also believed that the potential mitigating evidence would not have made a difference.

Now, Ayestas’ lawyers are arguing that he doesn’t need to prove that his trial lawyers failed to properly investigate his case because that’s what the funding request was supposed to accomplish. “It’s something of a circular standard,” Johnson says. In their appeal to the Supreme Court, they’ll try to prove that the Fifth Circuit’s “substantial need” test is “incompatible” with the goal of Criminal Justice Act: to provide quality legal representation for indigent defendants.

“Mr. Ayestas’s case is about the right to be fairly charged and defended,” Lee Kovarsky and Callie Heller, two attorneys for Ayestas, said in a joint statement after the US Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. “Mr. Ayestas had been denied his constitutional right to nondiscriminatory treatment and effective representation.” His attorneys say they want the high court to reverse the Fifth Circuit decision, get the funds to conduct an investigation, and finally give Ayestas a chance to be heard.

In an amicus brief, the American Bar Association strongly urged the Supreme Court to rule in favor of Ayestas, saying that the Fifth Circuit ruling jeopardizes the criminal justice system. “It threatens,” the Association writes, “the integrity, fairness, and reliability of the habeas process, of capital sentences, and ultimately of our criminal justice system.”