On Tuesday morning, Attorney General Eric Holder made a plea to states to overturn laws barring people convicted of felonies from voting. “It is unwise, it is unjust, and it is not in keeping with our democratic values. These laws deserve to be not only reconsidered, but repealed,” he said at a criminal-justice symposium in Washington, DC. “And the current scope of these policies is not only too significant to ignore—it is also too unjust to tolerate.”

As the New York Times pointed out, Holder’s comments were largely symbolic, since he doesn’t have the authority to personally enact changes. Regardless, Holder called attention to a huge, largely overlooked demographic. So what’s the lay of the land when it comes to felony disenfranchisement laws? Here are some facts to help clarify the issue.

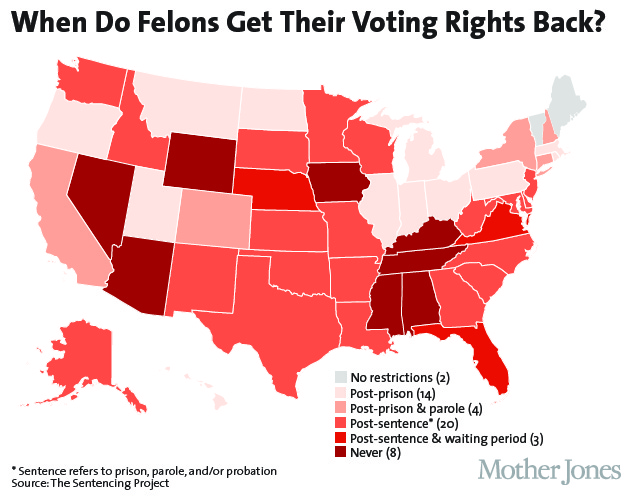

So how common are laws restricting felon voting? As we’ve reported before, nearly every state restricts the voting rights of people convicted of felonies. Only two states, Maine and Vermont, have no restrictions on voting; in these, felons can vote while still in prison. On the other hand, 11 states restrict voting even after a person has completed their prison sentence and finished probation or parole. Twenty states require completion of parole and probation before voting is allowed, and 14 states allow felons to vote after they leave prison.

Among states that bar voting even after a person has completed their sentence, the laws still differ greatly. In Alabama, only certain felony offenses result in disenfranchisement. In Florida, Nebraska, and Virginia, felons are able to vote after waiting periods between two and five years. And in Nevada, almost all felony offenders are completely barred from the polls (first-time, nonviolent felony convictions are exempt).

Eight states also completely bar people with misdemeanor convictions from voting while incarcerated.

How did this practice start? In his speech, Holder rightly pointed out that laws barring felons from voting are a relic of post-Civil War America. “After Reconstruction, many southern states enacted disenfranchisement schemes to specifically target African Americans and diminish the electoral strength of newly-freed populations,” he said. The Sentencing Project, a criminal-justice advocacy and research non-profit, confirms this, though notes that the revocation of voting rights dates back even further, to colonial America, when English colonists introduced the common law practice of “civil death,” a set of criminal penalties that included the stripping of voting rights. Later, as slavery was outlawed after the Civil War, the qualification of needing to own property to vote was gradually repealed across all states, notes the Sentencing Project. This meant that felony disenfranchisement policies “served as an alternate means for wealthy elites to constrict the political power of the lower classes.”

How many people do these laws really affect? Nearly 6 million Americans are barred from voting due to felony disenfranchisement laws. Moreover, the bulk of disenfranchised felons—75 percent—are no longer in prison. Approximately 2.6 million of those remain disenfranchised despite having completed all parts of their sentence (prison time, parole, probation) because they live in states that bar felons from the polls for life or require a post-sentence waiting period.

The number of felons without voting rights has ballooned significantly along with the growing prison population. The United States has the world’s highest rate of incarceration: Department of Justice statistics show that the number of people under correctional supervision has increased from fewer than 2 million in 1980 to more than 7 million by 2011. As a result, the number of disenfranchised felons has grown from 1.17 million in 1976 to 5.85 million by 2010, and at a rate of 500 percent since 1980.

Who gets the brunt of these laws? Felony disenfranchisement disproportionately affects people of color. Black men are incarcerated at a much higher rate than the rest of the population. According to the Urban Institute, 11.4 percent of African American men aged 20 to 34 were in prison in 2008, compared with just 1.8 percent of white men. One out of every 13 black Americans of voting age can’t vote due to criminal disenfranchisement laws, a number much higher than for any other demographic. This ratio is more stark in Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia, where more than 1 in 5 black adults is barred from the polls. Overall, 2.2 million black Americans have lost the right to vote because of felony disenfranchisement laws.

“The impact of felony disenfranchisement on modern communities of color remains both disproportionate and unacceptable,” Holder said on Tuesday. “These individuals and many others—of all races, backgrounds, and walks of life—are routinely denied the chance to participate in the most fundamental and important act of self-governance.”