Update, February 19, 2021: After this piece was published, Dr. Poon reported that the Georgia Department of Health restored vaccines access to the Medical Center of Elberton. The clinic will be able to order shots starting March 8 and resume vaccinations March 15.

It was a gloriously sunny Wednesday in early February, but Dennis Fowler was worried. The 77-year-old retired transit worker sat in the waiting room at his doctor’s office at the Medical Center of Elberton, a bustling clinic in rural Elbert County, Georgia. He was there for a routine appointment, but he had also come to ask his doctor about his COVID-19 vaccine. Weeks earlier, as soon as they’d heard they were eligible, Fowler and his wife called to make appointments to get their shots. The prospect of an immunization was a big relief: Dennis’ wife had kidney failure, and the two had spent the last 11 months under strict quarantine to protect her. But a few days earlier, the Fowlers’ doctor had called to tell them the bad news. They may not get a vaccine after all and would likely have to start the process all over again. “We’re concerned that we’ll get the virus before we get our shot,” Fowler said.

The Fowlers are not the only ones in this Georgia community whose vaccinations were canceled. In late December, the county had finished vaccinating health care professionals and first responders, so the Elberton Medical Center opened up appointments to what they’d thought was the next tier: people over age 65 along with essential workers, including teachers. Most people in town cheered this development. The schools had been open since August, since remote learning was impossible for the community’s many children who lacked internet access. But the doctors at the medical center didn’t realize that the Georgia Department of Health had changed the guidelines in January, and teachers were not eligible after all. When the Georgia DPH found out that the Medical Center of Elberton had vaccinated 177 school workers with Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, state health officials meted out a harsh punishment. They suspended all vaccine shipments until July and seized most of the remaining doses in the clinic’s freezer, leaving only enough for those who had already gotten their first dose to receive a second.

The state’s seizure of the clinic’s vaccine supply comes at a critical time. At the urging of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, many states have opened vaccine appointments to broader swaths of the community to speed the process and prevent wasted doses. Yet some local leaders are cracking down hard on anyone who doesn’t rigidly adhere to guidelines. The New York Times recently reported that a physician in Houston was fired this month for giving away vaccine doses that otherwise would have gone to waste. Many public health experts question the logic of disciplining providers. “I think it’s really important that we stop punishing groups or individuals for vaccinating those outside state or [national] COVID-19 vaccination guidelines,” Peter Hotez, a vaccinologist and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, told me for a previous story. The guidelines, he said, “mostly serve as a barrier or hindrance to vaccinations rather than their intended purpose.”

I visited the Medical Center of Elberton last week and chatted with Dr. Jonathan Poon, a physician who practices at the clinic, which is the largest in town and the main supplier of COVID-19 vaccines. He planned to distribute vaccines to the more than 3,000 patients the clinic sees every month. Now, like the Fowlers, most will struggle to get immunized elsewhere. About 70 percent lack private insurance, and many don’t have internet access they’d need to book appointments at other locations. “We’re in a very precarious situation,” he said.

Elbert County is in the far northeastern corner of Georgia, close to the South Carolina border. Many of its 20,000 residents are employed making tombstones and memorial statues out of stone—a mural downtown in Elberton, the county seat, boasts the town is “the monument capital of the world.” Trucks bearing slabs of granite rumble through the modest downtown, a square of municipal buildings and a few storefronts still open for business: Stan’s Music World, say, and Tena’s Fine Jewelry & Gifts. On Friday nights, people go to see the the Blue Devils football team from the high school play at the Granite Bowl stadium, which is carved out of 100,000 tons of blue granite. The people here live modestly: In 2018, the median household income was about $44,000, and nearly 20 percent lived below the poverty line.

On the day that I visited, I watched as residents stopped to greet each other around town. The older ladies had names like Sarabelle and Shelly Anne. “How’s your mama?” They asked neighbors at the pharmacy. “She managing okay?”

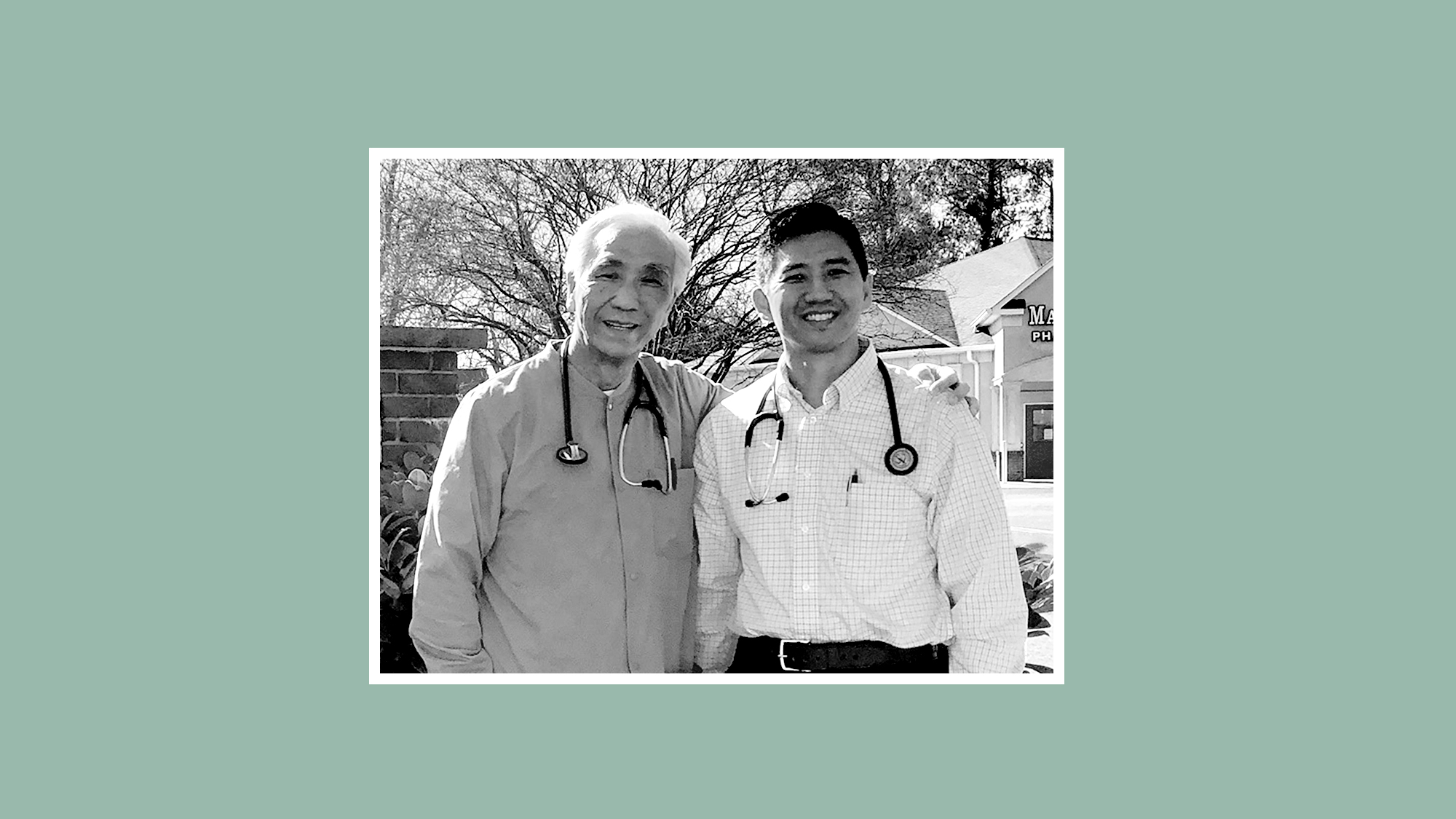

Almost everyone in this county knows Dr. Poon because he’s lived here almost his whole life. His family, originally from Hong Kong, moved to Elberton when Poon was 3 months old so his father could practice family medicine. Poon decided to follow in his father’s footsteps, and after medical school and residency, he moved back home to practice family medicine. Today, he sees patients down the hall from his father.

Poon, who has an unflappable air about him and speaks in a slow Southern drawl, isn’t used to being in the spotlight. He spends his days at the clinic, seeing local patients at all phases of life: children with sore throats, pregnant women, elderly people who need medication for diabetes. But in the last few weeks, Poon has appeared on TV news shows, talking about how much the people of Elbert County need the vaccines that the state took away. As he and I walked from the parking lot of the medical center to the pharmacy, neighbors greeted him like a conquering hero. “Thank you so much for what you’re doing for our town,” a man in a pickup truck said through his window. “I really mean it.”

When Poon and his colleagues heard in November that vaccines would be available by the end of the year, their planning went into overdrive. The clinic purchased a special freezer for $7,000, and a trailer to use as a vaccination clinic for $90,000. They wanted to make it as easy as possible for their patients to get vaccines, and they aimed to get the process started quickly. They saw how their community was suffering.

COVID-19 ripped through Elbert County this winter. So intense was the spread of disease that the small local hospital had to send patients to ICUs as far away as Jacksonville, Florida. The county EMS team has been stretched thin, transferring patients while also trying to provide regular emergency services to the county. In the three local nursing homes, the COVID-19 mortality rate was 30 percent. Poon estimates that 30 or 40 people died of the virus.

The county’s plight did not move the state public health department to reverse its decision despite Poon’s efforts. When I contacted the Georgia DPH for a previous story, spokesperson Nancy Nydam responded, “It is critical that DPH maintains the highest standards for vaccine accountability to ensure all federal and state requirements are adhered to by all parties, and vaccine is administered efficiently and equitably.” In other words, there was little hope for recourse.

When the state seized the medical center’s vaccines, the pharmacy next door, Madden’s, attempted to pick up some of the slack, applying to receive more vaccine doses from the state, a process that took several weeks. The gregarious head pharmacist, Don Piela, has been working hard to book appointments every day. As he stood behind the prescriptions counter, he told me he had to bring in help to cope with the demand for vaccine. His wife, who usually works as a pharmacist in another town, came into assist with booking appointments and performing vaccinations. The pharmacists also had to contend with unscrupulous line jumpers. An Atlanta couple in their 50s, for instance, drove two hours from the suburbs for a vaccine, claiming they were caregivers for the woman’s elderly mother, who lived in Tennessee. The pharmacists had to turn them away.

Piela told me he’s grateful that his pharmacy was able to help with vaccines, but he’s worried that the state’s decision to punish the medical center could have consequences beyond the pandemic. “If the state is coming in and suspending vaccines to a medical facility, there’s part of your population says, ‘Well, they must have been doing something wrong,’” he says. “If you damage the reputation of anybody, that’s damaging. But especially somebody that’s in health care, that’s really even more damaging.”

Dennis Fowler, 77, at the Medical Center of Elberton;

Kiera Butler/Mother Jones

Poon and his colleagues are working hard to try to convince state officials to restore their vaccine supply. They’ve been meeting regularly with county leaders, who have appealed the state’s decision twice, with no luck. State public health representatives responded with a letter stating that the decision to withhold vaccines will stand. Poon is worried that all the delays are wasting valuable time. Every day that Elbert County residents don’t get vaccinated is another day they could contract the virus. Meanwhile, more contagious variants are spreading quickly; the one that originated in Africa already has been identified in neighboring South Carolina.

Fowler, the 77-year-old whose vaccine appointment was canceled, is frustrated about being stuck in the house indefinitely, always worried about the fragility of his wife—and himself. If the state doesn’t restore vaccine shipments, he’ll make an appointment at Madden’s, but he doesn’t know how long he’ll have to wait—it could be weeks. He misses seeing his neighbors and going for a date with his wife to the Outback Steakhouse. He’s eager to get back to church. “I’m hoping something will come through,” he said, “and we will be able to get our shots.”

Standing in front of the clinic, Poon looked at the vaccine trailer his practice had purchased and shook his head. He intends to keep trying to impress upon the state that his patients deserve vaccines, and that he and his colleagues never meant to flout any rules. “There’s nothing we’re doing for personal gain,” he said. “We’re just trying to do the right thing.”

This piece has been updated.