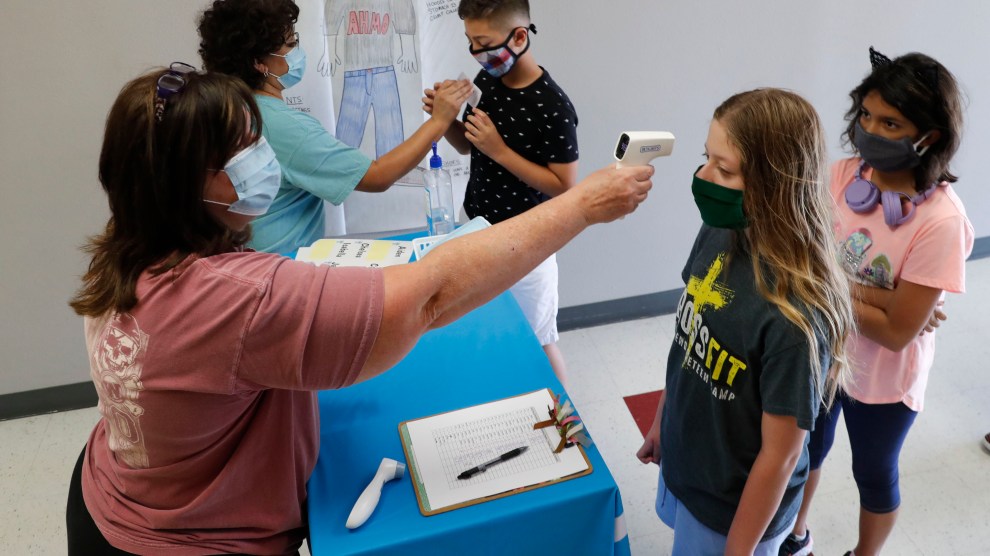

Amid concerns of the spread of COVID-19, science teachers Ann Darby, left, and Rosa Herrera check-in students before a summer STEM camp at Wylie High School Tuesday, July 14, 2020, in Wylie, Texas. AP Photo

There has been a mountain of stories written about kids, the coronavirus, and schools (including this definitively excellent piece by my colleague Jackie Flynn Mogensen). But last week, a small detail in a widely shared commentary from the medical journal Pediatrics caught my eye. “COVID-19 and Children: The Child is Not to Blame” examines studies of household transmission of the coronavirus in other countries and concludes that children rarely spread the virus to the other members of their household—usually it’s the adults who spread it to the children. It’s gotten a lot of attention. One of the authors, William Raszka, a pediatrician affiliated with the University of Vermont, appeared on a July 16 Fox News segment and advocated for the reopening of schools.

As others have pointed out, it’s tricky to compare studies of households in other countries to those in the United States because of a host of confounding variables. (Different lockdown policies! Different kinds of classrooms! Fewer mask refusers!). But let’s leave all that aside for a moment and just look at the studies themselves. This line about a study in Switzerland jumped out at me:

Of 39 evaluable households, in only 3 (8%) was a child the suspected index case, with symptom onset preceding illness in adult HHCs [household contacts]. In all other households, the child developed symptoms after or concurrent with adult HHCs, suggesting that the child was not the source of infection and that children most frequently acquire COVID-19 from adults, rather than transmitting it to them.

In other words, either a scientist or contact tracers interviewed families that got COVID-19 and asked when each household member’s symptoms began. If the kids’ symptoms began at the same time, or after the adults, the investigators assumed that the adults caught the virus and brought it home to the kids, rather than vice versa. Chinese studies that the authors looked at relied on this same method of “symptom chronology.”

Here’s the problem: The authors’ conclusion—that children rarely bring the coronavirus home and spread it to their households—assumes that the time between exposure and when symptoms appear in children is the same as that for adults. Given that we already know that children’s immune systems seem to behave differently with the coronavirus from adults, should we accept as a given that their incubation periods are the same? I put the question to Raszka, and he reassured me via email: “To the best of our knowledge, the incubation period of the virus is the same in children as it is in adults: 2-14 days.”

But Linda Saif, an immunologist with Ohio State University and the American Association of Immunologists, had a different take. “There are just too few studies, in asymptomatic children especially, to really understand the transmission dynamics,” she wrote to me in an email.” She pointed out a Chinese paper from April that reviewed the data on children and the coronavirus. It found that children’s average incubation period was 6.5 days, slightly longer than the 5.4 day average in adults. If that’s true, Saif wrote, the findings in the Pediatrics paper “may not reflect the true transmission picture.”

I want to be careful here: It would be hasty to assume the Chinese paper is the authority on the incubation period in children. As Saif noted, there’s probably not enough research for anyone to know for sure whether symptoms appear within the same amount of time for kids and adults. Here’s what would help: Studies that rely on frequent testing of everyone in households, rather than self-reporting of when symptoms started.

Also, considering the fact that some people with COVID-19 never show symptoms at all, an epidemiologist friend pointed out that we should be doing more “seroprevalence” studies—testing people in households for antibodies to determine who actually had the virus. One such study from Spain, published earlier this month in the medical journal The Lancet, found that children under age 10 were somewhat less likely than adults to have antibodies. That suggests that children may be less likely to acquire COVID-19 (though some people have theorized that people who don’t experience symptoms don’t make very many antibodies—and of course, antibody tests are notoriously unreliable).

Anyway, I bring all this up not to annoyingly punch holes in what seems like an otherwise reasonable commentary in Pediatrics—rather, to just point out that it is yet one more example of the crushing number of tiny details that could make a big difference in the impossible decisions facing parents, teachers, and leaders as the school year fast approaches.