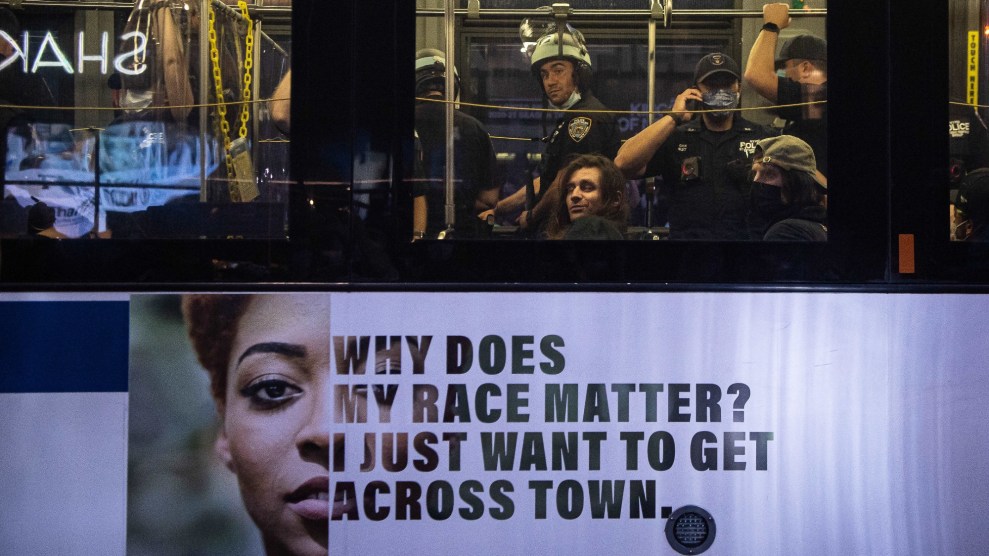

An arrested protestor looks out of a bus at a Brooklyn protest against the police killing of George Floyd on May 29, 2020. (Joel Marklund/Bildbyran via ZUMA)

Bus drivers around the country are refusing police demands to cart detained protestors to jail—and some now say they’re facing retaliation. On Thursday, after drivers in San Francisco, Minneapolis, New York and Washington, DC, declined to help crack down on protests against the police killing of George Floyd, Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) driver Erek Slater sued his employer in federal court for allegedly quashing a similar effort.

“CTA management shouted insults at me and threatened to fire me on the spot,” he wrote… “They said we couldn’t discuss if it was safe to drive CTA ‘police charters.’ They said we were promoting a wildcat strike…management continued to shout over us as they stated they were calling the police to forcibly disband the meeting.”

“At least three coworkers from just my bus garage have told me that they refused to drive the police charters—there are likely many more who have similarly refused, overcoming possible threats of ‘behavioral violations’ and loss of pay,” Slater wrote in his Facebook post.

Chicago drivers are following in the footsteps of transit workers in at least five other cities. In Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed, bus driver Adam Burch organized against a police request for buses to transport demonstrators near the city’s now-torched Third Precinct to jail, banding together drivers in his Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) local.

“As a transit worker and union member I refuse to transport my class and radical youth to jail,” Burch wrote in a Facebook post. “An injury to one is an injury to all.”

In New York, police tried to commandeer an MTA bus passing Barclays Center in Brooklyn. The driver walked:

NYPD commandeered a city bus for prisoner transport. The driver steps off the bus and refuses to drive it. Crowd cheering. #Brooklyn #BarclaysCenter #BlackLivesMatter #GeorgeFloyd pic.twitter.com/4F9IZ3sfDI

— Chad Loder (@chadloder) May 30, 2020

In San Francisco, a Muni driver asked to ferry prisoners left the city’s police in the dust:

SFPD scanner reporting on the bus brought in to arrest demonstrators: "We are no longer mobile. The bus driver left." ✊🚍✊

— Adam Hasan (@theadamhasan) June 1, 2020

According to a Twitter user monitoring San Francisco’s police scanner, the driver ditched the scene after pointing out she wasn’t getting paid—the usual prerequisite for driving a paddy wagon.

So far, every driver to turn down police orders has been unionized. New York City’s Transport Workers Union (TWU) Local 100 has a little bit of history resisting orders to work with cops: in 2011, when New York bus drivers were also asked to transport Occupy demonstrators, the union went to court for an injunction to keep NYPD from commandeering buses.

“TWU Local 100 supports the protesters on Wall Street and takes great offense that the mayor and NYPD have ordered operators to transport citizens who were exercising their constitutional right to protest—and shouldn’t have been arrested in the first place,” the union’s president said at the time. (The union lost the case.)

Tramell Thompson, a New York Subway conductor and Local 100 shop steward, says that drivers today feel the same way they did 10 years ago. He points out that jail and prison buses have seats, restraints, and other safeguards—and still aren’t deployed to active street uprisings.

“It’s the perspective of 99 percent of the bus operators,” says Thompson, who is Black. “Why would you want to put another city worker in the line of fire? The heavily armed police officers could barely control the protests. What if the operator gets beat up, or crashes? And not to mention—what happens with social distancing?”

“The officers have guns, they have pepper spray,” he adds. “I don’t think it’s our job to transport a prisoner. If we wanted to be correctional officers, we would have taken that test instead.”

Transit workers are some of the most vulnerable in any city: an average of four New York City subway workers are killed on the job every year, with more hit by trains but surviving. New York bus drivers develop ulcers so often the condition was once called “driver’s stomach,”a 2007 study found that transit workers are regularly exposed to carcinogens, and physical assaults—some racist—aren’t unusual. “A lack of basic preventive maintenance threatened worker safety” for decades, historian Joshua Freeman writes in In Transit, his history of the union. And, of course, they’ve faced repeated wage freezes and pension cuts.

COVID-19 posed yet another challenge. In New York City, several transit workers have already died on the job. (The pandemic has also created massive budget shortfalls for the agency, with ridership at historic lows.) Thompson, the TWU steward, says city agencies with fewer Black workers—like police, fire, and sanitation—got adequate protection first. “Forty-nine percent of the Transit Authority is Black. That percentage is even higher for the titles that actually need the PPE,” Thompson says. “They keep saying we’re heroes. Then why are they more protected when, as a conductor, I come across thousands of people per day?”

Transit workers have organized against on-the-job racism at least since the 1960s, when the NAACP joined with transit unions to protest racial discrimination. “Thousands of TWU members,” the union wrote in a Black History Month article, joined the 1963 and 1965 marches on Washington, as well as the 1968 Poor People’s March. In 2005, when New York transit workers went on strike over inferior benefits, risky working conditions, and tougher discipline meted out by city authorities, then-mayor Michael Bloomberg called the union “thuggish,” a dog whistle that infuriated members.

But workers of color are powerful within transit unions’ rank-and-file, and form a majority of many locals. Organized labor “needs to do more to support the protesters in the streets of America’s cities,” Washington, DC transit union head Raymond Jackson said Tuesday in an interview with In These Times. ATU Local 689, the union for DC’s Metro and bus system, is also refusing to carry detainees. (In 2018, Local 689 refused to transport white nationalists to a Unite the Right Rally.)

The local, which is majority Black, didn’t mince words in a public statement about the protests:

ATU Local 689 has moved this region for over 100 years. We fought, through organizing and striking, to transform low-paying transit jobs into careers with wages that you could raise a family on. But even with these good union jobs our members still routinely suffer from systemic racism and law enforcement abuses. We know firsthand that police are often the first people to arrive on the picket line, hours before the press shows up.

“It’s unforunate—there are [non-union] workers out there that might be penalized, might be retaliated against by their transit agencies,” said TWU Political Action Director Regina Eberhart. “We sound alarms whether you are union or not. Your protection comes first. We haven’t tiptoed around or been shy about the decisions members need to make to protect themselves.”

Action that started with the rank-and-file is beginning to trickle up. In Boston, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) just announced that it won’t help detain protestors or move police to rallies. Brian Lang, an MBTA board member, told WHDH in Boston that “we are not going to have the T used in any way, shape or form to inhibit people from expressing themselves.”

In Minneapolis, public schools and the university system—two other strong public-sector unions—have already cut or reduced relationships with police. Are transit agencies next?