Illuminati's car has a cool name: Seven.Illuminati Motor Works

I always get just a little excited when I read Jason Fagone‘s stuff, whether he’s writing about video game mavericks or scientists or the bizarre community of competitive eaters. I feel like I’m right there in the room, hanging out with his characters—hearing the noise, feeling the heat, catching the scents. His latest book is no exception. Out November 5 from Crown Books, Ingenious: A True Story of Invention, Automotive Daring, and the Race to Revive America is the tale of an amazing race: The 2010 Progressive Insurance Automotive X Prize offered $10 million in prize money for a safe, practical, long-range vehicle that could get 100 MPG or the voltaic equivalent (100 MPGe).

That’s be a high bar for Detroit, and an insane quest for a bunch of scrappy startups and backyard tinkerers, yet more than 100 teams entered the competition. Fagone, who hails from Philly, focuses on four of the top contenders, whom we get to know intimately. (Read a sneak preview of Ingenious here.) I caught up with the author to get his personal insights on the cars, the race, and why Detroit can’t seem to think outside the rolling steel box. But first, here’s a short book trailer…

Mother Jones: It seems like you had to choose which teams to follow fairly early on. Did you have to do any jiu-jitsu to make sure your contenders would make it to the finals?

Jason Fagone: I made some good guesses and got lucky. There was a team of students and teachers from a high school in West Philly, and I knew they’d do well because they’d beaten the likes of MIT in similar competitions. Another team, Edison2, interested me because they were pursuing this renegade strategy—instead of an electric car, they were building a small fleet of ultra-light, ultra-aerodynamic cars and powering them with motorcycle engines. I wanted to see if that could work.

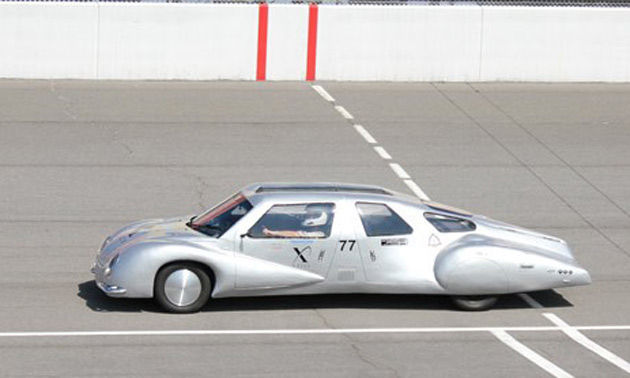

A third team I picked because they were colorful: Illuminati Motor Works was building an electric car from scratch in an old barn in the middle of an Illinois cornfield and doing it all with their hands—literally forging their own steel in a wood-burning stove. It was a 39-year-old guy, his wife, his father, his brother, and his friends. They didn’t have any money, though. I figured they’d get knocked out early.

MJ: And did the competition’s outcome surprise you?

JF: Illuminati surprised everyone. We all underestimated them. There were other surprises. The hybrid cars didn’t make it to the end. Neither did a lot of the electric conversions—production cars whose gas engines had been replaced with electric motors and battery packs. This wasn’t a contest that rewarded adaptations of existing designs. The teams that did well were the ones that built cars from the ground up, focusing on fundamentals like lightness, or aerodynamic efficiency, or both.

MJ: Which of these cars would you most like to drive?

JF: Probably the Illuminati car. It’s so dramatic and strange and beautiful. Those big fenders, the gullwing doors, the super-streamlined body. It’s the car I’ve had dreams about.

MJ: The goal of the X Prize was to build a practical, energy-sipping vehicle. How close did it come to accomplishing the practical part?

JF: The Prize was trying to strike a tough balance. The goal was to make cars that people could imagine parked in their driveways, which meant they had to be safe, handle well, and fit normal-sized humans. They couldn’t come off like science projects. On the other hand, the Prize wanted to help new ideas flourish, and that meant creating a kind of bubble—a space protected from the real world. Because it was the real world that had stifled automotive innovation for so long. It was the real world that had failed.

So there was a tension between creativity and practicality. The cars did have to conform to a considerable subset of federal safety regulations, but they didn’t have to be crash-tested. They did have to be nimble and durable and accelerate decently and fit actual humans, but they didn’t have to look or feel a certain way. They could present as alien. And ultimately the winning cars did look pretty alien. I think a lot of outside observers saw these cars and said, well, they’re not practical because they’re weird. I guess I’d argue that weird is in the eye of the beholder. The original Volkswagen Beetle looked weird, but it met a need, and now it’s a design icon. Also, what’s weird changes: It’s weird to pay $50 every couple of days to fill a heavy metal box with flammable liquid. It’s weird to know you’re warming the planet a tiny bit with every mile you drive.

MJ: Has the competition led to any real-world innovations that you know of?

JF: These are small teams, small companies. They were never going to be able to mass-produce the cars on their own. I think the hope was that some big auto company would swoop in and buy some of the technology. That’s what happened with the 2004 Ansari X Prize to create a reusable space plane. Richard Branson bought the winning plane and built a space-tourism company around it, Virgin Galactic. But no Branson-type figure has emerged in this case. The Obama administration has set very tough standards for fuel economy and emissions going forward, but the auto companies think they can hit the new targets without investing in the kinds of radical changes the X Prize cars represent.

MJ: It seems like X Prize officials were kind of making up rules on the fly. How did that affect the vehicles that came out of it?

JF: The organizers were basically staging an Olympics against the backdrop of one of the most highly regulated industries on Earth—and it went on for years. The contest was a grueling thing of staggering complexity. So yes, the officials made a number of adjustments as they went, which was tough on the teams, because it was hard enough to get the cars to work and conform to the existing rules without having to deal with new ones. One of the mechanics I met called the contest “the ultimate instant adaptation,” and that’s true. At the same time, the ability of the teams to improvise solutions on no sleep and ridiculous amounts of coffee was amazing.

MJ: The energy efficiency guru Amory Lovins has been talking up the Very Light Car concept for years. One of your characters, Oliver Kuttner of Edison2, actually put it into practice. Why has Detroit has been so reticent to go this direction—and do you think they will?

JF: Lovins is great, but he never built a bunch of prototypes. Oliver has built race cars, he’s driven cars professionally, he’s sold rare sports cars for a living. There’s a lot of stuff you can’t figure out until you build prototypes and test them. Also, Oliver’s cars use mostly aluminum and steel to keep cost down. The Lovins concept used advanced composite materials, which are more expensive. I think auto companies fear that very light cars will freak out consumers—that people will think they’re flimsy and unsafe.

MJ: Yeah, well that’s obviously a big concern. Oliver claimed that if you get in a head-on crash in a Smart car, you’re dead.

JF: A small, light car is obviously less safe in a head-on crash than a bigger, heavier car. You lose the battle of momentum. That was my first thought when I saw Oliver’s Very Light Car. Won’t this thing crumple?

But you can think about safety in a couple of ways. Safety is surviving a crash. It is also avoiding the crash in the first place—a light car is more maneuverable. And the Very Light Car seems to behave differently in a crash than a traditional car. Edison2 says they have some early data on this. Because the car is shaped like the skull of a bird instead of a box, and because it has wheels that extend away from the body, like an Indy Car, it tends to deflect instead of engage. This is credible, because Indy Cars crash like this. They glance and skitter. Race car drivers walk away from high-speed crashes all the time.

In one of my favorite passages in the book, the prize officials are arguing with an engineer from Edison2. They keep saying, basically, “Show me this car is safe in a traditional sense,” and the Edison2 guy challenges their assumptions one by one. He’s saying, essentially, “Define safe.” Now, there aren’t a lot of drivers willing to sacrifice safety for efficiency when they buy a car. But can you convince them to define safety in a different way? I don’t know. I do know that the auto companies aren’t interested in trying.

MJ: Yeah, you write how Detroit blew off the contest because it was a no-win situation. Explain that briefly.

JF: Let’s say GM entered a car and then lost to a bunch of ragtag racers and hackers and high-school students. GM would look bad. But even if GM won it would be in a bind, because then people would expect it to produce the winning car, and GM might not think there was a market for it.

MJ: I was struck by the fact that the average car today doesn’t get much better gas mileage than a Model T Ford. Which seems pretty pathetic. Admittedly, it wasn’t until the 1970s that high gas prices and climate change started emerged as a big deal, but Detroit still seems like a lousy innovator.

JF: We’re up to 25 MPG for the average new vehicle now. That’s across cars, trucks, SUVs, everything. It was 21 MPG in 2008, when the contest was in its infancy. The Model T got 20 or so. Cars today are obviously waaaaaay better than the Model T. And the average 2013 or 2014 vehicle is better than a 2000 vehicle or a 1990 vehicle—safer, less polluting, and more efficient.

So it’s not that automotive engineers are doing a bad job. They’re talented people. Actually, if it were only up to the engineers, cars and trucks would be a lot more efficient. But there are also designers and marketers and executives, and they like to make cars and trucks bigger and heavier and more powerful, because Americans like big, heavy, powerful vehicles, right? So the added weight and power cancels out a lot of the efficiency gains you might have seen.

I think the problem boils down to a mutually reinforcing conservatism in auto companies and consumers. The companies don’t think we’ll buy radically different kinds of vehicles, so we never get a chance to learn about them and get comfortable with them. Think about TV ads for cars and trucks: The messages are so meatheadedly toxic. Denis Leary talking about torque. I mean, kill me! Electric cars have a lot of torque, too, but you never hear that. And eventually it becomes as hard for us to imagine driving a really different kind of car as it is for the car companies to imagine making one.

MJ: So what was your personal takeaway from writing this book? Will your next car be a Tesla?

JF: I’m a journalist, dude! I can’t afford a Tesla! Seriously though, this is one of the frustrating things about electric cars now: The people who most need the fuel and maintenance savings electric cars provide are the people who can least afford the up-front costs.

Tesla is starting on the luxury end and working down to the mass market. The X Prize teams were mostly starting out with cars designed to be broadly affordable, and those designs were more interesting to me, because 1) I could actually see myself driving them, and 2) they tended to be more radical departures from the norm—the Illuminati vehicle and the Edison2 Very Light Car in particular. These are stunning, visionary objects! Illuminati’s electric car gets 207 MPGe. The Very Light Car achieved 102.5 MPGe with an internal combustion engine, which I think is kind of mind-blowing, and an electric version gets 245 MPGe. And they were created from scratch, in the middle of the Great Recession, by men and women without a lot of money or media pull.

This is what has stuck with me more than anything—the ingenuity of ordinary people when their backs are against the wall. A hundred and fifty years ago, when Walt Whitman was writing poetry about engineers and mechanics, what excited him about invention was the democracy of it. Today, the inventors who have influence in our culture are rich elites. We’ve gotten away from the old idea of invention. But it’s not too late to go back, and I think the X Prize is proof. There really is an incredible reservoir of energy and ability out there, waiting to be tapped, if we just broaden our definition of what an inventor is, and where big ideas are allowed to come from.