Incumbent Gov. Spencer Cox, left, talks with Utah Rep. Phil Lyman after Utah's gubernatorial GOP primary debate.Mother Jones; Issac Hale/The Deseret News/AP

On a stormy night in February, Phil Lyman made a campaign stop at the Taylorsville-Bennion Heritage Center, where a warm room full of conservatives had braved the weather to hear from several Utah political candidates. A Republican state representative, Lyman was pardoned by former President Donald Trump for a trespassing charge he picked up for driving an ATV in an illegal protest on public lands in 2014. Now he was running for governor.

When he got up to speak, Lyman asked the 50 or so attendees, “How do you like ‘Disagree Better’? How’s that feel to ya?” A chorus of boos and jeers erupted from the MAGA partisans in the crowd, who immediately recognized the reference to the pet cause of Lyman’s opponent, incumbent Spencer Cox. As chairman of the National Governor’s Association, Cox has spent the past year trying to convince Americans to “disagree better” and dial back the very sort of polarizing rhetoric Lyman specializes in.

Lyman told the crowd that basically, Cox’s initiative is predicated on a lie. The notion that “you either agree with me or you disagree with me on my terms. And that’s what’s happening right now in this in this state and this election with Governor Cox.” In fact, the whole effort was “a leftist, Marxist tactic to get people to drop their opinions. It’s manipulation to silence them.” He insisted that the whole enterprise might work if people on the other side would tell the truth, “Then maybe,” he said, “we could disagree better.”

The vitriol about Disagree Better is remarkable given how innocuous—even anodyne—Cox’s initiative seems. But Amanda Ripley, the author of High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out, isn’t surprised. She’s spent some time with Cox, and the NGA’s official Disagree Better website offers her book as a resource on depolarization.

“We’ve set up a system that rewards conflict entrepreneurs.”

What Cox is doing is “countercultural, going against a whole system of incentives and motions that are driving this thing. And that’s lonely and difficult to do, which is why you don’t see a lot of people doing it.” She suspects that Cox’s nod to civility poses a threat to people who benefit from political strife. “We’ve set up a system that rewards conflict entrepreneurs,” she told me. The sharp backlash against Cox’s campaign among the MAGA faithful “could be evidence that it is working,” she said. “In other words, if it bugs them, maybe that’s not a bad thing.”

Disagree Better got its start in Cox’s first race for governor in 2020 when he grew increasingly concerned about the overheated political discourse and its potential to lead to violence—a fear that came to pass on January 6. A few months before the November election, Cox had reached out to Chris Peterson, his Democratic opponent, and convinced him to make a joint ad arguing for civility in political discourse. The ad, hailed by Inc. magazine as a “masterclass in leadership,” went viral. In a follow-up ad, both candidates also committed to accepting the results of the presidential election.

Researchers at Stanford University’s Strengthening Democracy Challenge later found that the ad was one of the most effective interventions they’d tested in terms of reducing support for political violence and anti-democratic policies.

For Cox, the ad was not particularly risky. The last time a Democrat won a governor’s race in Utah was in 1980, and Cox went on to crush Peterson by more than 30 points. But apparently, the commitment to better public dialogue was sincere. When Cox was elected chair of the NGA in July 2023, he launched Disagree Better as his signature project.

The NGA website says Disagree Better “aims to change the political behavior of both voters and elected officials, showing that the right kind of conflict often leads to better policy, can be more successful politically than negative campaigning, and is the pathway to restoring trust in our political institutions.” For the past year, Cox has traveled the country promoting conflict resolution tools for people to use around the dinner table and in political life. He’s put an emphasis on volunteering and service projects as a way of stepping away from “doom scrolling” and helping Americans start talking to each other again.

The initiative has paired people like Supreme Court Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Amy Coney Barrett in public appearances to offer tips on how to “disagree agreeably.” The NGA has also launched a counter-programing effort of sorts by pairing up other governors from different parties, like New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) and Wyoming Governor Mark Gordon (R), to make public service announcements modeling civil political discourse the way Cox and Peterson did in 2020.

The initiative has gotten a glowing reception from the media and even President Joe Biden, but it doesn’t seem to have touched the irreconcilable differences at the grassroots level in Cox’s home state. Among MAGA activists like Lyman and his followers, partisans don’t just disagree on policy positions. They see Democrats and liberals as evil; their hatred of them is a moral, not a policy, position. They’re not interested in bridge building, a view reinforced by right-wing media and extremist politicians who traffic in owning the libs to get attention. As Lyman explained in a March tweet, “We don’t need to ‘disagree better.’ We need to Stand for Something!”

Lyman is something of a folk hero in certain quarters of Utah, particularly among the sagebrush rebellion sympathizers. In 2014, Lyman, then a county commissioner, organized an illegal ATV protest after the Bureau of Land Management closed a canyon in southern Utah to motorized vehicles to protect fragile landscapes and Native American burial grounds. Ryan Bundy, son of outlaw rancher Cliven Bundy, joined Lyman and dozens of ATV riders in the canyon just a month after his family had organized an armed standoff with the BLM at their Nevada ranch. The agency had tried to impound cows that Cliven had been illegally grazing on public land for years.

A jury found Lyman guilty of misdemeanor trespassing, and a judge sentenced him to 10 days in jail. Far from condemning the flagrant disregard for the laws he was supposed to uphold, many outraged Utah Republican politicians, including Cox, put up thousands of dollars of their own money to pay Lyman’s legal fees—a tacit endorsement of his behavior. “We are proud to support one of our own,” Cox said, after adding $1,000 to a pile of cash collected by lawmakers at a meeting in the state capitol. “Commissioner Lyman is one of the finest individuals I know.”

In 2018, Lyman was elected to the state legislature, and two years later, President Donald Trump pardoned him. Thus enabled by the Republican Party, Lyman took his message to the governor’s race.

In Taylorsville, he expanded his attack on Disagree Better, claiming it had been cooked up “by the Carnegie Institute,” an organization that started the NGA, adding that the NGA was founded by motivational speaker “Dale Carnegie.” (Actually, it was founded by industrialist Andrew Carnegie.) Lyman warned that the NGA dates back to the Rockefellers and has ties to the World Economic Forum, a body conspiracy theorists frequently accuse of trying to seize global power and forcing people to eat bugs.

Moreover, he claimed, the NGA had been created by early 20th century eugenicists, “eugenics meaning, you know, wiping out masses of people. They apologized for that, by the way,” he continued in a mocking tone, “Sorry about that eugenics thing but we’ve got some other really good ideas and one of them is Disagree Better.”

The audience was with him, as were the wider ranks of hard-core state Republicans. Utah has an unusual system for selecting candidates in party primaries. It uses both a nominating convention and a traditional statewide primary ballot. At the GOP convention, a candidate must win at least 40 percent of votes of the 4,000 or so delegates to advance to the statewide primary. But because the convention delegates have become so extreme, the state legislature changed the law in 2014. Now candidates can choose to circumvent the conventions and secure a spot on the primary ballot by gathering signatures, so that more Utah voters could have a say in the process.

Cox got the 28,000 signatures needed to score a place on the primary ballot. Lyman opted to take his chances at the nominating convention, where he was the odds-on favorite and only needed about 1600 votes to get on the primary ballot. Cox also participated in the April convention, a much more hostile forum for him than the TED talk he’d given a few days earlier.

Utah delegates booed Cox when he took the stage. “Maybe you’re upset that I signed the largest tax cut in Utah history,” he said in response, rattling off a list of his achievements in office. “Or maybe it’s something much more cynical. Maybe you hate that I don’t hate enough.” The crowd was unpersuaded. Lyman trumped Cox, winning nearly 70 percent of the vote and joining Cox on the June primary ballot.

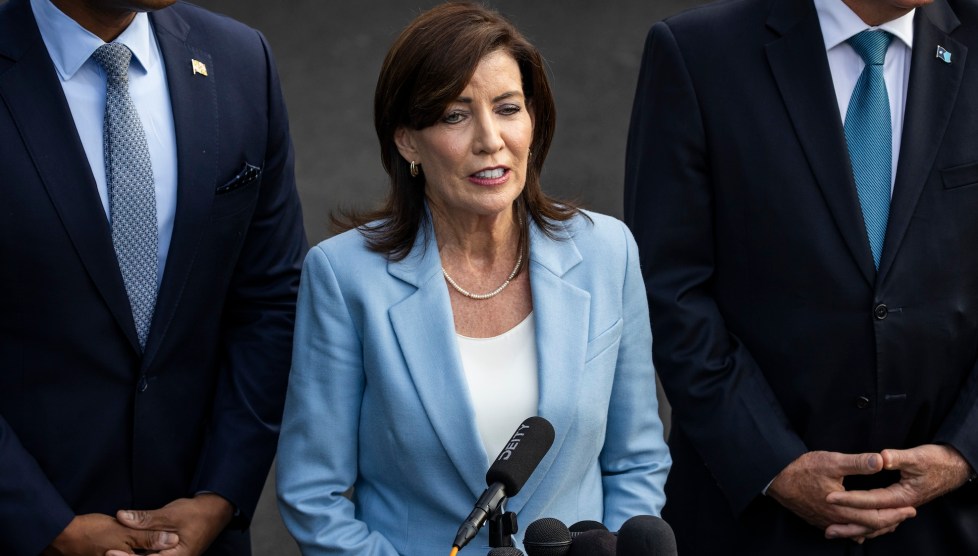

Cox’s campaign to reduce political animus hasn’t increased his popularity with some liberals either. After Sotomayor insisted to a crowd in DC that the justices had a cordial relationship even when they disagreed on the law, Linda Greenhouse wrote an April piece in the New York Times headlined, “Who Cares if Supreme Court Justices Get Along?” A veteran Supreme Court reporter, she dismissed all the talk of happy lunchroom encounters and cited the string of cases and ethics breaches that were currently leaving the court—and the country—more polarized than ever. “What counts is not how the justices treat one another,” she wrote, “but how they treat the claims of those who come before them.”

In Utah, liberal residents have criticized Cox for calling for comity at the same time he’s signed off on the legislature’s bans on abortion and gender-affirming care for trans people. During a Disagree Better event in DC, he called such health care “gender mutilation surgery.” Cox also approved an extreme partisan redistricting map in 2021 that carved up heavily Democratic Salt Lake City into four districts, ensuring that Democrats never had a majority in any of them.

Utah voters had passed a ballot measure in 2018 to create an independent redistricting commission that would draw new congressional maps in 2020. But the state legislature’s Republican supermajority overturned the restrictions on gerrymandering, ignored the commission’s proposed boundaries and imposed highly partisan maps anyway. Furious Utah residents filed a lawsuit over the move that’s still pending.

These kinds of anti-democratic power grabs are exactly the sorts of structural problems that inflame the current partisan hostilities. They are also a big reason why research shows that most efforts to get individual citizens to “disagree better” have been spectacular flops. Even interventions like Cox’s 2020 ad that Stanford researchers praised only moved the needle by about 3 percent after two weeks. The improvements were simply overwhelmed by cable news and divisive political leadership.

“Interventions to reduce affective polarization will be ineffective if they operate only at the individual, emotional level,” wrote Rachel Kleinfeld, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in a September 2023 essay reviewing the existing studies on the subject. Ignoring the role of conflict entrepreneurs like Trump and Lyman will only increase cynicism “when polite conversations among willing participants do not generate pro-democratic change.”

Indeed, in a state where Democrats have been systematically shut out of the government, cynicism runs deep. But Ripley says what Cox is trying to do is critical if the country wants to head off more political violence like that seen at the US Capitol on January 6—or worse. “You have to do everything,” she said. “You have to have people building relationships across big divides, whether their racial, religious or political, and having conversations at the dinner table, and you have to have leadership. You have to change the political incentives around how we elect people.”

Cox has his work cut out for him, especially in Utah, where Lyman’s campaign forced Cox to respond to the misinformation and outright lies it spread, all while trying to stick to his promise not to run a negative campaign. “The hardest thing in politics these days is running a positive and honest campaign,” he lamented in a tweet. “Lies and negative campaigning are cheap and cowardly.”

Despite all the criticism of Disagree Better, Utah voters seem inclined to let Cox keep going. On June 25, he won the GOP primary, beating Lyman 57 to 43 percent. He will face State Rep. Brian King (D) in the November general election.

The primary wasn’t close, but that didn’t stop Lyman. Even before the election, he’d hinted that he might not accept the results. “I will say this: I will be checking the results of the election,” he told the Salt Lake Tribune earlier this month, throwing shade on the state’s election system, which he claimed suffered from a “huge lack of transparency.” Four days before the election, Lyman had also called for an audit of the signatures that Cox used to get on the ballot, claiming that there was an “unrealistically high” number of valid signatures.

On election night, Lyman took a cue from the man who pardoned him and refused to concede after the AP called the race for Cox. “Call it dangerous if you want but I’m not buying it,” he tweeted.

Faced with Lyman’s continued refusal to disagree better, a clearly frustrated Cox told KSL NewsRadio, “There’s decency and then there’s whatever this is. I don’t care if he concedes or not.”