<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-60864799/stock-photo-an-aerial-view-of-a-crop-duster-or-aerial-applicator-flying-low-and-spraying-agricultural.html?src=4sNAhS4cVdHG8cwROxYRQg-1-0">B Brown</a>/Shutterstock

For defense against the fungal pathogens that attack crops—think the blight that bedeviled Irish potato fields in the 19th century—farmers turn to fungicides. They’re widely sprayed on fruit, vegetable, and nut crops, and in the past decade they’ve become quite common in the corn and soybean fields. (See here and here for more.) But as the use of fungicides has ramped up in recent years, some scientists are starting to wonder: What are these chemicals doing to the ecosystems they touch, and to us?

A new paper in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications adds to a disturbing body of evidence that fungicides might be doing more than just killing fungi. For the study, a team of University of North Carolina Neuroscience Center researchers led by Mark Zylka subjected mouse cortical neuron cultures—which are similar in cellular and molecular terms to the the human brain—to 294 chemicals “commonly found in the environment and on food.” The idea was to see whether any of them triggered changes that mimicked patterns found in brain samples from people with autism, advanced age, and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Eight chemicals fit the bill, the researchers found. Of them, the two most widely used are from a relatively new class of fungicides called “quinone outside inhibitors,” which have surged in use since being introduced in US farm fields in the early 2000s: pyraclostrobin and trifloxystrobin.

Now, it’s important to note, Zylka told me in an interview, that in vitro research like the kind his team conducted for this study is only the first step in determining whether a chemical poses risk to people. The project identified chemicals that can cause harm to brain cells in a lab setting, but it did not establish that they harm human brains as they’re currently used. Nailing that down will involve careful epidemiological studies, Zylka said: Scientists will have to track populations that have been exposed to the chemicals—say, farm workers—to see if they show a heightened propensity for brain disorders, and they’ll have to test people who eat foods with residues of suspect chemicals to see if those chemicals show up in their bodies at significant levels.

That work remains to be done, Zylka said. “What’s most disturbing to me is that we’ve allowed these chemicals to be widely used, widely found on food and in the environment, without knowing more about their potential effects,” he said.

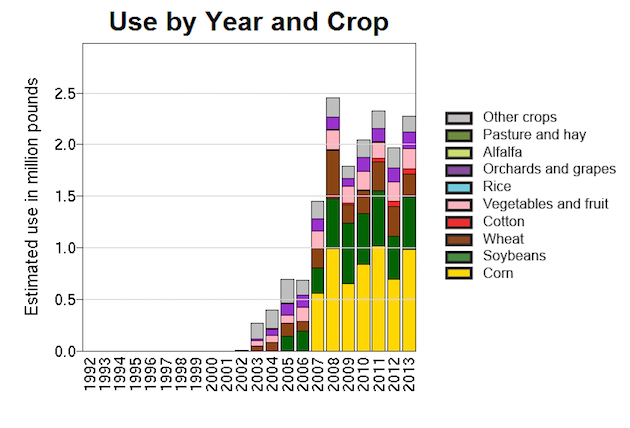

How widely are they used? The paper points to US Geological Survey data for pyraclostrobin, a fungicide that landed on the UNC team’s list of chemicals that trigger “changes in vitro that are similar to those seen in brain samples from humans with autism, advanced age and neurodegeneration.” It’s marketed by the German chemical giant BASF’s US unit under the brand name Headline, for use on corn, soybeans, citrus fruit, dried beans, and more. BASF calls Headline the “nation’s leading fungicide.” The USGS chart below shows just how rapidly it has become a blockbuster on US farm fields.

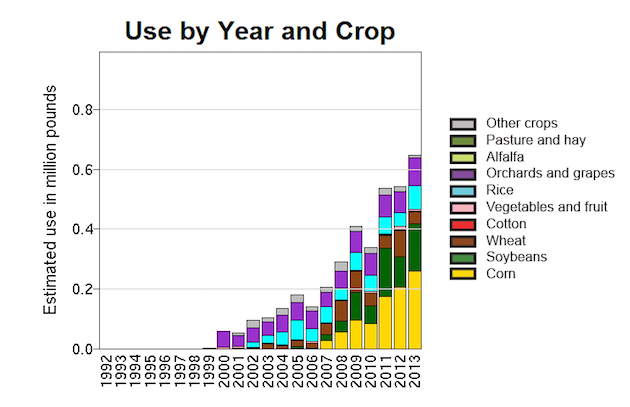

Then there’s trifloxystrobin, which also made the UNC team’s list. Marketed by another German chemical giant, Bayer, trifloxystrobin, too, boasts an impressive USGS chart, reproduced below.

In an emailed statement, a BASF spokeswoman wrote that cell tissue studies like Zylka’s “have not demonstrated relevance compared with results from studies conducted on [live] animals.” She added, “While the study adds to the debate of some scientific questions, it provides no evidence that the chemicals contribute to the development of some diseases of the central nervous system. This publication has no impact on the established safety of pyraclostrobin when used according to label instructions in agricultural settings.” A Bayer spokesman told me that the company’s scientists are looking into the Zylka study and “don’t have any initial feedback to offer right now.” He added that “our products are rigorously tested and their safety and efficacy is our focus.”

As Zylka’s team points out, both of these chemicals turn up on food samples in the US Department of Agriculture’s routine testing program. Pyraclostrobin residues, according to USDA data compiled by Pesticide Action Network, have been found on spinach, kale, and grapes, among other foods, in recent years, while trifloxystrobin has been detected on grapes, cherry tomatoes, and sweet bell peppers. Again, there hasn’t been sufficient research to establish whether these traces are causing us harm, Zylka stressed, but since they are entering our bodies through food, he thinks more research is imperative.

Meanwhile, a disturbing picture of the ecosystem impacts is emerging. These same chemicals also leave the farm via water. A 2012 US Geological Survey study found pyraclostrobin in 40 percent of streams in three farming-intensive areas. In another 2012 USGS study, researchers looked for a variety of pesticides in the bed sediments of ponds located within amphibian habitats in California, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Maine, and Oregon. Pyraclostrobin was the most frequently detected chemical of all, turning up in more than 40 percent of tested sites.

Studies suggest that as the fungicides leach out into the larger environment, they’re harmful to more than just fungi. Oklahoma State researchers found BASF’s pyraclostrobin-based fungicide Headline deadly to tadpoles at levels frequently encountered in ponds. And a 2013 study by German and Swiss researchers found that frogs sprayed with Headline at the rate recommended on the label die within an hour—a stunning result for a chemical meant to kill funguses, not frogs. I wrote about the study when it came out. “These studies were performed under unrealistic laboratory conditions,” a BASF spokeswoman told me at the time. “The study design neither reflects conditions of realistic agricultural use in practice nor the natural behavior of the animals.”

Then there are honeybees. In a 2013 study, a team of USDA researchers found pyraclostrobin and several other fungicides and insecticides in the pollen of beehives placed near farm fields—and that bees fed pyraclostrobin-laced pollen were nearly three times more likely to die from common gut pathogen called Nosema ceranae than the unexposed control group (more here).

Meanwhile, the industry is enthusiastically marketing these products. “Headline fungicide helps growers control diseases and improve overall Plant Health. That means potentially higher yields, better ROI and, ultimately, better profits,” BASF”s website states. “It can help secure a family’s future, fund a college education, finance an equipment upgrade, or maybe buy just a bit more of a vacation for the whole family.” Such supposed benefits aside, I wish we knew more about the environmental and public-health costs of these increasingly ubiquitous chemicals.