Something to protect: a plate featuring feijoada, a classic Brazilian black bean stew. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/43674804@N00/3227880572/in/photolist-5VeJrj-5VeAc9-965xsh-95L5Wq-2MLxz-9miaev-9miaMe-9mmfB1-9mmfaw-aWjC6i-aWjE9P-9mmoW1-9mmBKh-9mmxaC-9mmxp7-9midc2-9mmgxh-9mig8g-9mmkZY-9mio4r-9mipkM-9mmzBU-9mibDF-9mmnK5-9miueg-9mmncf-9mmvwq-9mmCM3-9mmhCd-9mifst-9miizp-9mmouh-9minAi-9minNc-9mmuuJ-9mijoe-9mmprW-9mmttj-9mmzTu-9mihRV-9mmza9-9micMD-9mmqDG-9mmrjj-9mixNT-9miog6-9mmmg9-9migQx-9mih3a-9mmAUf-9mmtgs">Carla Arena</a>/Flickr

In the cover story of a recent Atlantic, David Freedman argued that the answer to the obesity problem lies in kinder, gentler convenience food, engineered to be enticing while containing less sugar and fat. I pushed back, skeptical that Big Food could hyperprocess us a healthy diet even if it wanted to. Freedman and I rekindled our conversation in a joint interview on Minnesota Public Radio:

“>

I got to thinking about the dustup when I read an essay, published in the journal PLOS Medicine by Brazil-based nutrition researchers Carlos Monteiro and Geoffrey Cannon, on how that country is dealing with its own emerging obesity crisis. The piece delivers insights into the relationship between Big Food’s dominance of a nation’s food system and obesity, as well as ways of thinking about the crisis that we might consider here in the United States.

“>

The authors point out that gigantic US and European food companies like McDonald’s, Kraft, and Unilever are moving aggressively into Global South countries like Brazil because they’ve largely saturated their home markets. According to their research, industrialized food reaches a saturation point in a given country when “ultra-processed products supply around 60% of total calories,” as has been the case for two decades in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, they write. They add some pungent commentary on how, here in the US, the industry is groping for a way to grow despite the saturation point:

Indeed, in the US, consumption of sugared cola and other soft drinks is now declining from a very high peak, and transnational corporations have moved into “designer water” and soft drinks for which health claims can be made because the drinks have been reformulated to contain more substances chemically identical to micronutrients or the dietary fibre found in whole foods.

(Here’s my take from a while back on sugary soft drinks tarted up with health claims.)

Meanwhile, Big food is pushing aggressively into Brazil:

During our work on this essay, we went for lunch to a workers’ restaurant near the University of São Paulo, where a traditional freshly cooked meal of rice, beans, and a choice of meat, together with mixed salad, cost the equivalent of $US 6. We noticed that the bottled water offered was “made” by a once Brazilian company now owned by Coca-Cola, and that the artisanal water-based ice lollies containing fruit juice, which are still sold by pedlars on Brazilian beaches and supplied by traders to simple restaurants, had been replaced by fatty, sugary brands of Nestlé ice cream. These same ice creams, together with other Nestlé “popularly positioned products,” which are “targeted at and bought by low income consumers”, are now being sold door-to-door in the outskirts of several Brazilian cities, on trains and subway stations, in retail chains that sell electronic and house appliances, and also on “floating supermarkets” that take Nestlé products to remote Amazonian villages.

The authors posit a linear relationship between the percentage of calories provided by Big Food and a nation’s obesity rate. Here’s how it’s playing out in their home country:

In Brazil, the consumption of ultra-processed products has already risen from less than 20% of calories in the 1980s to 28%, but this figure is still well short of 60%, the possible saturation level. Similarly, the current prevalence of obesity in Brazil (14% among adults in 2009), has some way to go before it reaches the levels seen in countries like the UK and the US (currently 24% and 34%, respectively).

And how do they propose to prevent Brazil’s obesity rate from rising to match those of the UK or US? Interestingly, they are suspicious of efforts, like those promoted by The Atlantic’s Freedman, that focus solely on Big Food as the solution to the problem. Within “UN, government, public health, and scientific circles,” they write, the idea has taken root that the way to fight chronic conditions like obesity is through “public-private partnerships, meaning collaborations between government and the “private sector” (a topic I took up a while back here).

They identify two big-picture problems with this approach. The first is that the private sector is too often defined narrowly, to mean “transnational and other large suppliers, manufacturers, and distributors of ultra-processed products and their raw materials, together with allied and associated corporations and institutions.” The definition excludes small players working on the ground in a country to grow and distribute food—as the authors put it, “low-input and ‘organic’ producers and growers, the horticulture industries (again, with a few exceptions), food and farming cooperatives, and family and smaller manufacturers.” In other words, companies like Coca-Cola are considered a worthy partner for governments, while, say, a fruit growers’ cooperative is ignored.

The second problem is that public-private partnerships can act end up merely delivering an official endorsement for highly processed food at the expense of fresh fare. The Atlantic’s Freedman should take note:

Within countries where food systems are already more or less saturated with ultra-processed products, these committees are mainly focused on proposals to adjust the formulation of ultra-processed products so that they contain, for example, less salt and trans-fats or more synthetic micronutrients. But such reformulation often allows manufacturers to advertise their products as “healthy,” which is likely to result in sustained or even increased purchase and consumption of such products, additional displacement of fresh and minimally processed foods, and therefore further increases in obesity, diabetes, and other chronic diseases. Moreover, the reformulation strategy of transnational corporations may have the effect of heading off legislation designed, for example, to sharply limit or prohibit the advertising and marketing of ultra-processed products to children. [Emphasis added.]

On a hopeful note, they write that despite Big Food’s recent growth in Brazil, the country “retains, at least in part, its traditional food systems,” and “protection of public health still remains a prime duty of government that has not eroded as it has in other countries.” And they point to a couple of recent moves by the Brazilian government to bolster and improve those systems, rather than idly watching while they get dismantled by Big Food. Here’s one: “[B]y law, all Brazilian children are entitled to one daily meal at school, at least 70% of the food supplied to schools must be fresh or minimally processed, and a minimum of 30% of this food must be sourced from local family farmers.”

There’s no reason why we can’t do similar things here in Fast Food Nation. (Our school lunches, despite recent reforms, remain mostly dismal.) It’s true, as Monteiro and Cannon state, that “traditional food systems of fully industrialized high-income countries like the US and the UK were largely displaced generations ago.”

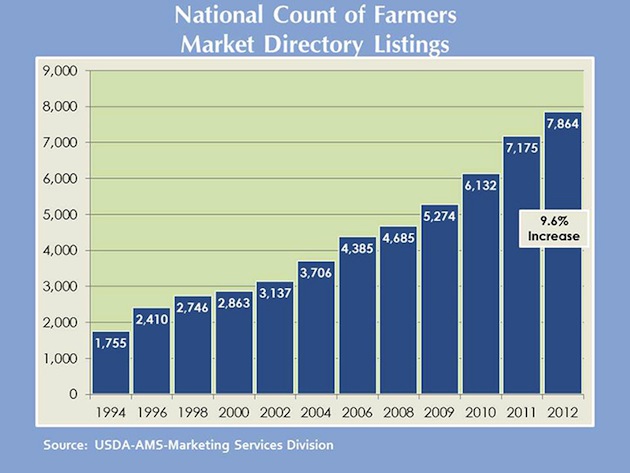

But there’s a burgeoning movement, taking root all across the country, to rebuild alternatives to Big Food. There are many ways to illustrate this point. Here’s an easy one—the ongoing rise of farmers markets:

Farmers markets, CSAs, urban “food justice” projects, burgeoning collaborations to rebuild local and regional food networks—these on-the-ground assets represent an alternative vision for reforming the US diet: one that doesn’t involve hoping that Big Food can clean up the public health catastrophe it has wrought.