Paul Hakimata/Shutterstock

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has taken a lot of heat lately for its failure to nominate any actors of color for the Oscars, two years running. But race may not be Hollywood’s biggest diversity problem.

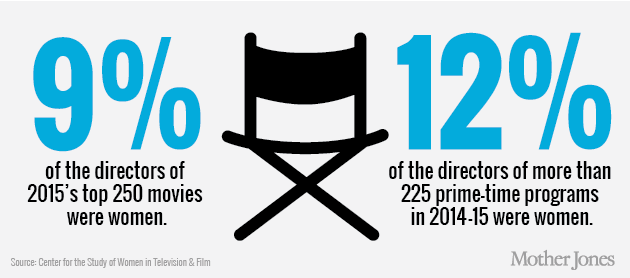

The number of women directing big-budget films and TV series is stunningly low. Only 9 percent of the directors of last year’s 250 top-grossing movies were female, according to the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University. And women accounted for just 12 percent of the directors on more than 225 shows on prime-time TV and Netflix during the 2014-15 season.

The numbers are even more depressing for women of color. Black women directed just 2 of the 500 top-grossing films from 2007 to 2012, according to a study by the Women’s Media Center. Women of color directed only 3 percent of TV episodes during the 2014-15 season, notes a report from the Directors Guild of America.

The numbers aren’t improving, either. The share of big-budget directorial jobs going to women was lower last year than it was 15 years earlier, when it peaked. The TV numbers have been stagnant in recent years. “Women’s underemployment has simply not been perceived by many executives as a problem,” says Martha Lauzen, director of the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film, who has been gathering data on the topic for nearly two decades. “As a result, little meaningful action has been taken to correct the gender imbalance.”

The shunning of female directors is so rampant that the feds have gotten involved. In October, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which enforces anti-discrimination laws in the workplace, began interviewing female directors so that “we may learn more about the gender-related issues” they face. The probe came after the American Civil Liberties Union called on the EEOC to investigate the film industry’s systemic failure to hire women directors. The agency contacted at least 50 women in October, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

In an email, an EEOC representative acknowledged that the agency has “had further discussions” with the ACLU about its data and conclusions, but she said she could not comment on any investigation—or even confirm whether one exists. The EEOC, she wrote, encourages the industry to “publicly address the serious issues raised by the ACLU.”

Part of the problem, female directors told the ACLU, is that male producers often make hiring decisions based on tired stereotypes. Women said they were steered toward romantic comedies and “women-oriented” movies, while the most lucrative, action-driven films went almost exclusively to men. Female TV directors said they were offered shows for women and commercials for “girl” products while being overlooked for car commercials or other types of shows.

What’s more, Hollywood producers, who are overwhelmingly male, will often pick directors from short lists that contain few women, or through word of mouth. Women who haven’t yet directed a major project often end up on the sidelines.

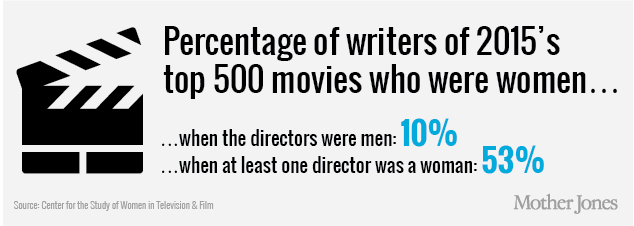

Hiring more female directors could be key to improving Hollywood’s gender imbalance. When women are in charge, Lauzen found, the number of women employed behind the scenes increases considerably: On high-grossing films directed by men in 2015, women made up 10 percent of writers, 19 percent of editors, and 10 percent of cinematographers. When a woman was the director, female representation on the crew increased to 53 percent of writers, 32 percent of editors, and 12 percent of cinematographers.

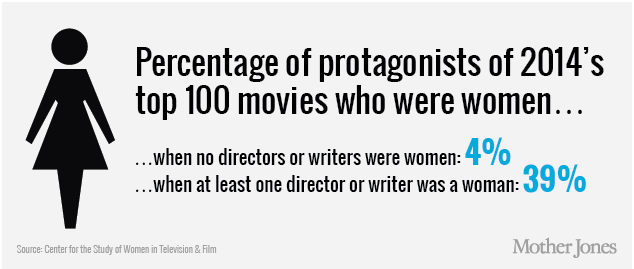

At stake in all of this, Lauzen explains, is how women are represented on-screen. “People tend to create what they know. Having lived their lives as males, men tend to create male characters,” she says. “If women comprised a larger percentage of film directors, we would see more female characters, particularly as protagonists, onscreen, and we would see more fully developed, multidimensional females.” In another study, Lauzen found that women accounted for just 4 percent of protagonists in films with exclusively male directors or writers. But when at least one woman was writing or directing, nearly 40 percent of the protagonists were female.

TV is way ahead of the film industry on that front—think Scandal‘s Olivia Pope, How to Get Away With Murder’s Annalise Keating, or Jane Villanueva of Jane the Virgin. As X-Files star Gillian Anderson (who says she was initially offered about half of David Duchovny’s salary to reprise her role as Dana Scully) recently put it to Mother Jones: “Television isn’t the issue. There are a lot of female characters on TV who are intelligent, and a good enough portion of them aren’t all about the date and the car and the plastic surgery. It’s in film that it’s lacking…I think there’s a lot of [female directors] out there—I just don’t think their material gets made. Studios don’t believe they’ll have an audience if women make it. A lot of female directors can’t pay somebody to hire them.”

The Directors Guild’s current agreement with film and TV studios has no quotas for women but asks employers to “make good faith efforts to increase the number of working” women and minority directors. Last May, the Guild’s Women’s Steering Committee considered altering the agreement to treat women and ethnic minorities as separate diversity categories. Supporters of the change felt that it would create more opportunities for women—particularly women of color, who would qualify for both pools. The idea never made it out of committee.

But since the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission got involved in October, there has been some movement within the industry. Two weeks after the agency started its probe, several dozens of Hollywood’s leading CEOs, producers, writers, and directors met privately to discuss solutions to their industry’s gender problem. Among the ideas discussed were introducing “unconscious bias” training across the industry, creating more recruitment programs to identify and hire talented women directors, and rewarding studios that show a commitment to achieving gender parity in hiring.

Gillian Thomas, an attorney at the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project, says that while an investigation as expansive as this one will take time, she thinks it will ultimately produce results. “I think women in male industries is a priority of the agency’s,” she says. “So I have faith in the process working.”