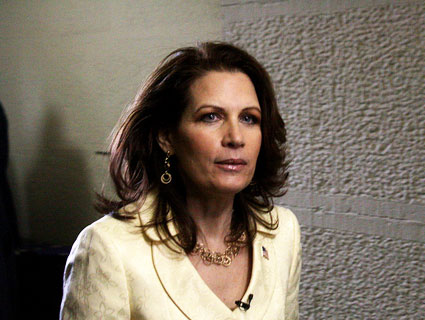

Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.)<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/teambachmann/5922907947/sizes/z/in/photostream/">Michele Bachmann</a>/Flickr

Fifty-seven pages into her new memoir, Core of Conviction, Michele Bachmann makes a confession. “When I say something wrong, I’m hard on myself, because I’m trying to communicate information accurately,” she writes. “And so as someone who talks for a living, I’ve learned to check, double-check, and triple-check my sources. And yet I still make a mistake or two!”

So we’ve heard. Bachmann’s book, her first, hits stores this week, just in time for the Black Friday rush, and given the Minnesota congresswoman’s lagging poll position, it might be the best thing that’s happened to her in months. In the totally nuts, absolutely wild, up-is-down, Newt-is-up 2012 GOP primary campaign, there’s no better miracle elixir for a rough patch than a book tour. Herman Cain’s rise in the polls corresponded with his decision to stop campaigning in early primary states, and instead hawk his book; Newt Gingrich, who has spent much of his campaign selling documentaries and children’s books, is experiencing his own unexpected surge just as he’s released his latest work of historical fiction. If Core of Conviction can’t save Bachmann’s campaign, nothing will.

It’s a short book, and an easy enough read devoted in large part to correcting her biography as it’s been reported in the press. But in doing so, she breaks her own rule with regularity.

You don’t have to read far to find the first whopper—it’s on page one. It’s a yarn the candidate has spun frequently in campaigns past regarding her unlikely candidacy for state Senate in 2000. As Bachmann describes it, she had made a spur-of-the-moment decision to show up for the district nominating convention but had no intention of running for the seat herself; she just wanted to be a part of the democratic process. She was dressed in moccasins and a torn sweatshirt. She was coaxed into putting her name on the ballot, stumbled through her speech, and somehow defeated both the Republican incumbent Gary Laidig and the party machine.

“I was just doing my duty as a citizen, speaking out,” she writes. “It was like that wonderful Norman Rockwell painting from the forties, Freedom of Speech, in which an earnest man speaks out at a town meeting, politely but firmly.”

But that account puts Bachmann in conflict with Bachmann. In 2001, she bragged to the St. Paul Pioneer-Press that she had been planning her primary challenge a year in advance of the convention because of Laidig’s support for the state curriculum standard, Profile of Learning, as well as Minnesota’s compliance with a federal program called Goals 2000. She told the Stillwater Gazette prior to the election that “I told [Laidig] that if he’s not willing to be more responsive to the citizens, then I may have to run for his seat.” As Laidig told The New Yorker‘s Ryan Lizza, referring to Bachmann’s citizen crusade, “Michele came to me on several occasions and to my face said, ‘If you don’t vote to get rid of School to Work and Profiles, I will run against you.'” (Bachmann devotes the special appendix in Core of Conviction to fleshing out her critique of the Clinton-era education policy.)

The floor that day in suburban Mahtomedi was filled with anti-Profile activists—almost all of whom had been riled into political activism by Bachmann herself. By some accounts, there were even pro-Bachmann campaign signs.

There’s enough to dispute within the first 13 pages that by the time she announces, on page 14, that she was born in Waterloo, Iowa, you almost want to ask for a birth certificate. Political memoirs have been known to inflate details from time to time; that’s the point. But Core of Conviction takes things further. Bachmann’s description of her tumultuous stint as a founding board member at New Heights Charter School in Stillwater, Minnesota, is another example. “Yes, we were Christians, but we never sought to impose Christianity on our students,” she writes. That would come as a surprise to New Heights parents, who have noted her efforts to bring creationism into the classroom.

Her account is also contradicted by the school’s board meeting minutes, which, as I reported in July, chronicle efforts by some of the school’s founders to run the school according to the “20 principles of Christian management.” Per the minutes, board members took issue with Bachmann’s efforts to promote Christianity in the school, fearing that they were crossing a line when it came to the separation of church and state. An investigation by the school district confirmed those fears.

“Ultimately, [her husband] Marcus and I saw we wouldn’t succeed in restoring the school’s original focus, and so I and other board members stepped down,” Bachmann writes. Which is putting it mildly. Under fire at the tumultuous final school board meeting, the future presidential candidate joined in a prayer to ward off the evil spirits she felt had crept into the room.

The whitewashing is the all the more striking given the passion with which she writes about her religious awakening, her calls throughout the book to fight back against moral relativism, and her insistence that America’s greatest values are enshrined in its Judeo-Christian core. Much of the book is spent, quite sincerely, explaining how her faith informs everything she does; of course she wanted faith to be a part of the education system.

That said, there are some redeeming moments. Bachmann’s personality comes through, at times earnest, at times endearingly tacky. She describes her confusion the first time she saw a reference to the Beatles song “Michelle” (“Why the two letters?”) and recalls the most important piece of advice she received from President George W. Bush, while sitting in the back of the presidential motorcade en route to a fundraiser in 2006: “The president looked at me and said, ‘room temperature water is healthier.'” Thanks, Mr. President!

The book is heavy on exclamation marks—there are 109 of them in 208 pages—and figurative language. “The political waters back home in Stillwater have not been still since,” she writes on page 12. “There would be no stillness in my life in Stillwater,” she writes on page 113. When describing a particularly romantic date with Marcus, she gets poetic: “Now I could speak. And I did. Like water from a spring brook.” She’s also really into pepper, a quirk she inherited from her grandmother.

Toward the book’s grand finale, in which she makes the case for why conservatives should hop on the “freedom and prosperity train” and support her campaign, Bachmann describes the bureaucratic gluttony of Obama-era Washington. “[T]he number of limousines owned by the federal government rose by 73 percent during the first two years of President Obama’s administration. What an amazing statistic!” But not really, as it turns out: The increase was solely attributable to a long-term plan by one agency, implemented before Obama took office, and as FactCheck.org explained, “‘limousine’ includes armored vehicles and sedans, not just actual limos.”

Bachmann blames Obama for increasing the number of Department of Transportation employees making $170,000 from one in 2007 to 1,690 in 2009. Except, as FactCheck notes, “At least two-thirds of those employees were receiving more than $170,000 before Obama took office.” One moment she’s lamenting the sky-high tax rates of the 1970s; the next moment she’s labeling the considerably lower tax rates of the Obama era “unprecedented.” On “Obamacare,” she rattles off a list of whoppers that read like a Politifact greatest hits: It funds abortion; it will cost 800,000 jobs; it creates death panels; it contains $105 billion in secret spending (there was nothing secret about it); and it would cause 114 million Americans to lose their existing private coverage (the report she’s referencing simply says that, if a public option existed, 114 million Americans would choose to switch to it.)

The text is littered with Bachmannalia. She refers to the federal government as the “givernment” and helpfully informs readers that, while unsuccessful, her legislation to repeal incandescent lightbulb regulations “sent an electric shock through the country.” The Troubled Assets Relief Program is labeled a “$700 billion blank check,” which is a logical impossibility. “My campaign plan is simple,” Bachmann writes, as she lays out an agenda to restore America to greatness. “I am going to say true things.”

Why start now?