Illustration: Jack Unruh

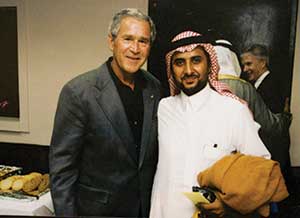

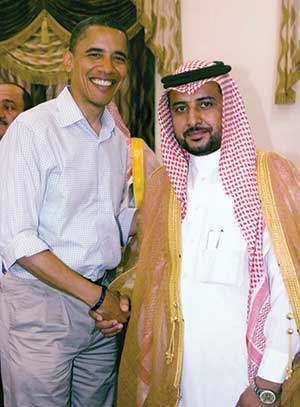

It’s a bright day in February, and I am in a pink villa on the outskirts of Fallujah, sitting with a tribal sheikh and a Marine commander as they hunch over a plate of truffles. The sheikh is Eifan Saddun al-Isawi, a charming 33-year-old Iraqi in a red-checkered kaffiyeh, a brown dishdasha, and DKNY wraparound sunglasses who uses phrases like “sons of bitches” when he talks about Al Qaeda with Americans. He is the head of Fallujah’s Sahwa, or Awakening, council, the Sunni militia hired by the United States in early 2007 to fight its enemies in Iraq, and he’s become one of the American military’s go-to guys in the city, as evidenced by the photos on his walls of him with George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

Sheikh Eifan Saddun al-Isawi poses with two prominent patrons.

The American officer, Lt. Colonel Chris Hastings, apologizes for forgetting to bring Eifan “magazines with pictures of pretty ladies” and congratulates him for winning a seat in the provincial elections. He proceeds to tell Eifan to make sure that a certain someone the Marines are “concerned” about doesn’t make it into local politics. Eifan assures him he’ll see to it.

Hastings also needs Eifan on the hearts-and-minds front: The Marines recently killed a teacher strapped with a suicide belt, and Hastings wants the sheikh to convince his community that the Americans aren’t bloodthirsty warmongers. The Awakening councils don’t officially work for the Americans anymore—the Iraqi government now pays the $300-a-month salaries of Eifan’s men—but Eifan obliges immediately. “Give me pictures and I will give it to all the imams and sheikhs to show them he was wearing a belt,” he says. He then presses the lieutenant colonel to release some of his friends from prison (Hastings agrees), offers him an antique hunting rifle (Hastings declines), and steers the talk back to the topic he’s been hinting at throughout the meeting: American cash.

“Just tell the colonel to give me the contract. Come on, man. You know I’ll do a good job,” he says. Over the years, Eifan’s gotten used to the way Americans do business in Iraq. Working with them has made him a millionaire.

Hastings isn’t particularly proud of that fact. He has been trying to wean the sheikh off the no-bid contracts the Pentagon has been giving him and his relatives for the past few years. The military has put “a lot of money” into Sheikh Eifan, he explains, and “he’s gotten a little bit greedy.”

Eifan is a beneficiary of what some American personnel call the “make-a-sheikh” program, a semiofficial, little discussed policy that since late 2006 has bankrolled Sunni sheikhs who are, in theory, committed to defending American interests in Iraq. The program was a major part of the Awakening, which the Pentagon has touted as a turning point in reducing violence and creating the conditions for an American withdrawal. It was also a reinstitution of a strategy started by Saddam Hussein, who picked out tribal leaders he could manipulate through patronage schemes. The US military didn’t give the sheikhs straight-up bribes, which would have raised eyebrows in Washington. Instead, it handed out reconstruction contracts. Sometimes issued at three or four times market value, the contracts have been the grease in the wheels of the Awakening in Anbar—the almost entirely Sunni province in western Iraq where Fallujah is located.

The US military has never admitted to arming militias in Iraq—or giving anything more than $350 a month to Anbari tribesmen to fight alongside Americans against Sunni resistance groups and Al Qaeda. But reconstruction payments, sometimes handed out in shrink-wrapped bundles of $100 bills, have left plenty of extra for the sheikhs to “help themselves as far as security goes,” as one Marine officer describes it, or “buy guns,” as Eifan’s uncle, Sheikh Talib Hasnawi, puts it.

From the Pentagon’s perspective, the money gave Iraqis a reason to support—or at least stop attacking—the United States in the province where more American soldiers had been killed than in any other. But it has also put security in western Iraq in the hands of powerful, heavily armed men whose cooperation is based not on loyalty to Baghdad or Washington but on a consistent flow of cash.

When Eifan registered his construction firm, Al-Thuraya Contracting Co., with the Iraqi government in 2003, it barely had $4,000 in capital. Today, though, business is booming. “I’m going to turn Anbar into Dubai,” he boasts.

Dubai isn’t quite what comes to mind as I watch four men mixing cement and stacking cinder blocks, setting the foundation for a clinic a couple of miles from his compound. The 3,000-square-foot building is the most recent of Eifan’s several “patronage projects,” as Hastings describes them. The military paid the sheikh $488,000 for it, yet Hastings estimates that it will cost around $100,000 to build. “That’s, you know, a pretty good profit margin,” he says—close to 80 percent. In comparison, KBR, the largest military contractor in the country, cleared 3 percent in profits in 2008. Halliburton scored around 14 percent.

Most of these kinds of projects are funded through the Commander’s Emergency Response Program, which allows batallion commanders to hand out reconstruction contracts worth up to $500,000 without approval from their superiors or Washington. CERP was founded in 2003 by then-Coalition Provisional Authority head Paul Bremer, who took its initial funding from a pool of seized Iraqi assets. Over the next five years, the program disbursed more than $3.5 billion in American taxpayer dollars. A Pentagon manual called “Money as a Weapon System” broadly defines CERP’s purpose as providing “urgent humanitarian relief and reconstruction.” The guideline has been interpreted liberally: CERP recently funded the development of a $33 million Baghdad International Airport “Economic Zone” with two hotels, a remodeled VIP wing, and a $900,000 mural depicting an “economic theme.”

CERP regulations explicitly prohibit the use of cash for giving goods, services, or funds to armed groups, including “civil defense forces” and “infrastructure protection forces”—Pentagonspeak for militias. But Sam Parker, an Iraq programs officer at the United States Institute of Peace, says it’s “no real secret” among the military in Iraq that CERP contracts are inflated to pay off sheikhs and their armies. Austin Long, an analyst with the Rand Corporation who has been studying the Awakening, says it is not unusual for contracts to go to sheikhs who, like Eifan, had little or no construction experience before the 2003 invasion. “Contracts are inflated because they are only secondarily about the goods and services received,” explains Parker. “It’s very problematic. You are rewarding the guys with the guns.”

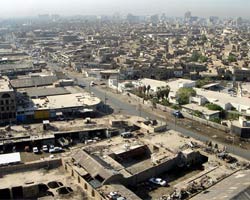

Five years and hundreds of millions of reconstruction dollars later, Fallujah remains a shell. The “city of mosques” still has minarets with gaping holes left by American rockets during the 2004 siege. Men wander the streets; the World Food Programme says 36 percent of Fallujans have no chance of employment. The city gets no more than eight hours of electricity a day. Sewage fills the streets; a sewer project is four years behind schedule and has cost $98 million, more than three times its original budget. Building after building is nothing but broken-down cement frames. Some have been repurposed by the Iraqi army as watchtowers, others by women drying their laundry. Bullet holes pockmark everything.

I walk down the city’s main thoroughfare guided by a police officer. As I chat with a man about the collapsed building beside his shop, my notebook out, a group of men approach, eager to air their grievances. “When any country in the world gets money for reconstruction, it shows. But not here,” says a burly man who calls himself Nabil. “The contractors just slap something together and put the money in their pockets,” he says, slipping invisible bills into an imaginary shirt pocket. “Reconstruction contracts are deals between the Americans and their collaborators. I don’t want to name names, but people who didn’t have cigarettes in their pockets now have piles of money and brand-new, bulletproof cars.”

Later, Eifan smirks as he tells me his black armored BMW is 1 of 11 in the entire world. Unlike the white Land Cruiser the Americans gave him last year (in 2008, the military spent $1.54 million on vehicles for “Anbari leaders”), he swears the sedan—which he claims is worth $420,000—was not a gift. “It will resist any automatic weapon and it will hold up pretty well in a bombing,” he tells me, smacking one of its two-inch-thick windows. I grab an energy drink from the leather-covered, refrigerated liquor cabinet in the backseat as we admire its hidden cameras and a security feature that lets Eifan speak to people outside the car without rolling down the windows.

A few years ago, hardly anyone outside a green stretch of date orchards and wheat fields a few miles south of Fallujah knew who Eifan was. Born in Iraq but raised in Saudi Arabia, he didn’t know much about his homeland except that his father was poisoned by the Baath Party’s secret services in Egypt five years after he’d tried to lead an uprising in 1976. Eifan moved back to Iraq in 2001 with a degree in accounting, married, had three kids, and started a small construction company.

He says the American invasion “was a big mistake,” but coming from a family of shrewd businessmen, he knew an opportunity when he saw one. “I’ll do business with anyone. I don’t care who it is,” he says. He built a small militia “for protection” and, according to a close associate, started running construction materials to American bases. He says he tried to convince the Americans not to lay siege to Fallujah. Eifan considers the thousands of Iraqis subsequently killed heroes.

Today, being in Fallujah as a guest of Sheikh Eifan is like seeing Baghdad from the Green Zone. His home is a small fortress, surrounded by 12-foot walls, with a shack of armed men guarding the entrance. Suicide bombers have killed several of his militiamen at the front gate; many others have lost their lives in the 12 assassination attempts Eifan claims he has survived. Next to a 10-foot-tall picture of the sheikh in a paisley dishdasha, two pickups mounted with machine guns are constantly ready to go. They follow him almost everywhere.

While Eifan slips away for meetings on American bases or appointments with politicians, he leaves me with his armed assistants, who brusquely dissuade me from asking too many questions, including about their boss’ whereabouts. While he is gone, people trickle in and gather in his diwan, or sit in lawn chairs around his empty swimming pool. Some days, upwards of 20 men await his return. Sometimes they watch TV or play with a remote-controlled helicopter, but mostly they sit in silence over dark, sweet tea.

When Eifan returns, the men hop to their feet and form concentric circles around him in hopes of stealing his attention. Sometimes, he hands out envelopes of cash. Other times, he ignores everyone and does side wheelies on his ATV around the compound. When I met Eifan for the first time, he was coming back from a meeting with the prime minister. He ordered his men to start up the grill so he could cook the crab one of his American friends had just brought him from Florida.

Before we pull out of a gas station along the Baghdad-Amman highway, Eifan peels several crisp 25,000 dinar notes (roughly the equivalent of $20 bills) off a fat wad he keeps in his pocket and hands them to a police officer through his barely rolled-down window. “Go buy yourself a Pepsi,” he tells him. The two trucks filled with Eifan’s armed men position themselves in front of and behind the BMW.

Eifan plays the Sahwa’s orchestral anthem on the stereo and looks at me in the rearview mirror. “I did not cooperate with the Americans to ruin Iraq,” he says. “I cooperated with the Americans because they were a reality enforced on Iraq.” He blames the United States for giving rise to the extreme violence that tore Iraq apart, but personally takes credit for making this route safe. “It used to be impossible to drive on this road,” he says. He points to an overpass where he says Al Qaeda hung two people. We float past crumpled cars, remains of the suicide bombings that once targeted outsiders who ventured into Anbar.

I don’t have to worry about being pulled out of the car by masked gunmen, in part because the attacks stopped when the hijackers realized the Americans paid better. The original leader of the provincial Sahwa, and a close friend of Eifan’s, Sheikh Abdul Sattar Abu Risha, was well known for running a successful ring of highway bandits. Initially, he had tried to befriend Al Qaeda, but then Al Qaeda began raiding Anbar’s roads to raise funds, and a turf war ensued.

And so Abu Risha’s alliance with the Americans began. Eifan and several other Anbari sheikhs fled to Jordan in 2005, but a group of Marines convinced them to return at the end of 2006. It’s not clear what promises were made, but when the sheikhs came home, they and other Sunni tribal leaders began fighting the insurgents alongside the Americans. Eifan initially refused to join Abu Risha’s Sahwa—Abu Risha belonged to a different tribe—but once the Americans started giving Abu Risha contracts, Eifan changed his mind.

Getting a full accounting of the make-a-sheikh program is nearly impossible; at press time the Pentagon was still responding to multiple Freedom of Information Act requests. Yet data from Pentagon reports to Congress indicate that in Fallujah, CERP funds more than tripled in the year starting in September 2006. Anbar has received $424 million in CERP funds, more per capita than any other province ($297 per person, twice as much as Baghdad). Abu Risha, once one of Anbar’s most notorious criminals, hosted the first “reconstruction fair,” in Ramadi. He was assassinated in September 2007, just days after meeting with George W. Bush.

The main point of the CERP contracts “was to try to get people to realize that if they played by the rules we were establishing, then they would have a chance to actually play the game,” explains Commander Edward Robison, who worked as a Navy reconstruction officer in Anbar in 2007. And “play the game,” he clarifies, means “make money.” As he tells it, the US military or Iraqi politicians would handpick a pliable sheikh, then award him funds that he could hand out as he saw fit. “If you were an individual who was not going to be one of the players in the community, you did not get work. The ones who were going to be players, they got work.”

Funneling billions of dollars into an unstable country “has raised the stakes of corruption considerably,” says the US Institute of Peace’s Parker. According to Transparency International, Iraq is tied with Burma as the world’s second most corrupt country, behind Somalia. Payoffs and profiteering are widely seen as “the cost of doing business” in Iraq, Parker says. He believes the US government doesn’t care whether Iraqis are left with a corrupt country when our troops leave. “We are fine with letting the Iraqis have their own corrupt system for themselves.”

Maki al-Nazzal, a former UN field worker who grew up in Anbar and knows Eifan’s family, notes that even American troops have not been immune to the temptations of graft. “Officers want their cut,” he says. “It used to be 15 percent of the contract.” In March, investigations by the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) led to the arrest of several commanders taking kickbacks. Three South Korean Coalition soldiers were convicted for stealing $2.9 million in CERP funds in a bribery scheme, and a US Army captain was indicted for stealing $690,000 in CERP funds after a late-model BMW and a Hummer showed up in his driveway back in Oregon.

SIGIR is currently investigating around 80 cases of corruption and waste. But it has turned a blind eye to CERP’s function as a payoff dispenser for the military. Inspector General Stuart Bowen may have bigger fish to fry—by his own accounting, at least $8.8 billion in reconstruction funds went missing between just October 2003 and June 2004. (Oversight of the reconstruction of Afghanistan has also been spotty at best; see “No Accounting for Waste.”)

Oversight for CERP projects of less than $500,000 is almost nonexistent, according to the Government Accountability Office. Yet in its audit of CERP in 2008, the GAO decided against digging any deeper. “We did not really look at any of the contracting practices or how they were awarded or that kind of thing,” says Sharon Pickup, the GAO’s director of defense capabilities and management. SIGIR representatives declined to be interviewed for this story, as did the spokesperson for the Department of Defense inspector general.

Eifan at ease (above). A “lower level” guest of the sheikh (right).

Meanwhile, Congress continues to approve CERP funds for Iraq—approximately $1 billion is in the works for next year—under the assumption that the program’s sole purpose is humanitarian relief and reconstruction. Most members of Congress remain unaware that the American alliance with the Sunni tribes has gone beyond the now defunct security contracts that paid their fighters’ salaries. “There’s not been a lot of discussion about [CERP],” says Sen. Byron Dorgan (D-N.D.). “The program has largely given the commanders in the field the ability to use funds with what appears to me to be very little accountability.”

Back in Eifan’s diwan, I am sipping tea with a roomful of men when the sheikh bursts in, sweeping a long stick across the room. “Nobody say a word!” he shouts. Four heavies march in behind him and throw a man on the floor, his feet, hands, and eyes tightly bound with kaffiyehs. A man in green camo with an AK-47 blocks the doorway.

The captive’s chest heaves as Eifan stands over him, stick in hand. An hour earlier, the sheikh was shouting into his cell phone about a botched reconstruction contract. Eifan stands to lose $50,000, and the compound has filled with murmurs about when and how he’ll explode. The crime of the man curled up on the floor isn’t related; in fact, no one is sure he’s committed a crime at all, but some goatherds have accused him of being involved in a kidnapping. Eifan fires questions at him while the room holds its collective breath. “Don’t stop to think of lies!” Whack! The stick comes down against his thigh.

Fallujah’s police chief shows up, clearly deferent to Eifan’s authority. Finally, satisfied with the interrogation, Eifan orders his men to bring tea to the shaken detainee. “We have many levels of guests here,” he says, looking over at me. “This one is on a lower level.” The police carry the man away. I ask Eifan what will happen to him. “They will interrogate him in a different way,” he says flatly.

After everyone leaves, he takes me into another room, turns on a Lebanese beauty pageant, and pours some whiskey. He says his form of tribal justice is the only effective kind. “We still can’t trust the police. That’s why people come to me,” he says. Despite winning the seat on the provincial council and his occasional meetings with the prime minister and other top politicians, Eifan shows little faith in the government. He confesses that his reason for making common cause with the Americans wasn’t only to fight Al Qaeda; he also wanted to gain power over the Shiites, whom he sometimes spitefully calls Iranians, who control the government in Baghdad. “They wanted to desecrate Sunni land, repress Sunnis, and kill Sunnis. I was certain that we would not be able to get out of this problem unless we put our hand in the hand of the Americans.”

That was two years ago, and since then reconstruction money has bought a lot of guns—guns the Awakening councils now aren’t shy to threaten to use against fellow Iraqis. The councils’ last beef was with the Iraqi Islamic Party, their main rival in the January provincial elections. For months leading up to them, assassinations had been taking out leaders on both sides. The current Sahwa leader in Anbar, Ahmed Abu Risha (brother of the slain Abdul Sattar Abu Risha), threatened to make Anbar “like Darfur” if the IIP won the vote. It was a flashback to the sheikhs’ original conflict with Al Qaeda: a fight for control over the spoils of war. The new battle, according to a report by the International Crisis Group, “centered on the control over resources, notably reconstruction contracts.”

Peter Harling, senior Middle East analyst with the ICG, says the volatility in Anbar indicates why buying allies, as appealing as it may seem, is unfavorable to a stable, democratic future in Iraq. “The pillaging of state resources is not a particularly good strategy,” he says. “It creates a culture of predators and a lot of resentment from those who don’t take part in those contracts. You might lavish one tribal leader with contracts but alienate 10 others.” Rand analyst Long is also concerned that the strategy is shortsighted and could lead to unpredictable shifts in political loyalties when the United States cuts off the funding. “The question is, are the people we picked to be our friends going to continue to be supported by the Iraqi government?” he says. “If the people we were paying off don’t get that kind of support, what does that do to stability? I think it’s a real risk.”

For now, the Iraqi government seems set on keeping a lid on Anbar by sticking to the American policy of buying off the sheikhs with contracts. When Eifan and I drive to Baghdad, we stop on a bridge overlooking a small river and a dam. The dam’s overseer approaches the car and explains to Eifan that the provincial council told him they couldn’t afford to fix it.

“How much did you tell them it would cost?” Eifan asks. The man hands him a slip of paper. “I’ll get the prime minister to sign off on this and I’ll do the work myself,” Eifan says. “But first, write a new proposal. And double the price.”