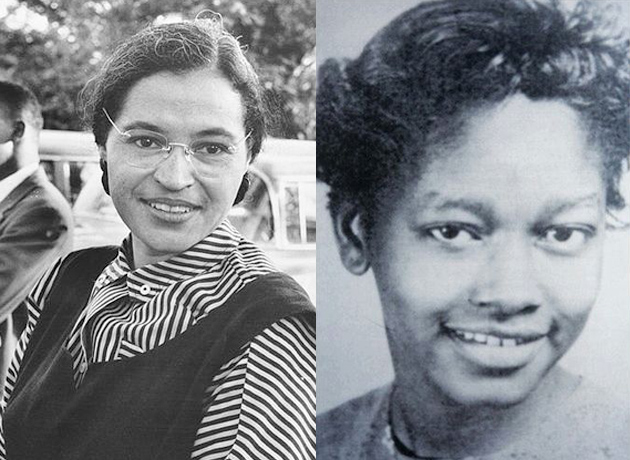

Rosa Parks, left, and Claudette Colvin.Parks photo from Ebony via <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Rosaparks.jpg">Wikipedia Commons</a>.

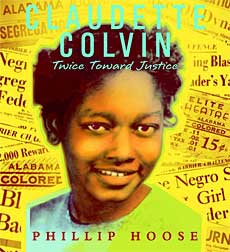

In his warm-up for the first-ever inauguration of a black American president, the actor Samuel L. Jackson stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial, speaking of the sacrifices of everyday people to bring about the event we were witnessing, including the well-worn story of Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on the bus. Jackson told the story as the old history books do, more or less the way my child, then six years old, had learned it at school: Parks, a department store seamstress en route home from work, told the police she hadn’t boarded the bus intending to get arrested. She was simply tired, and wanted to get home like anyone else. But the true story was far more nuanced, as revealed in Claudette Colvin, Twice Toward Justice, by Phillip Hoose, which is written for teenage readers.

Parks was certainly brave. (Standing up to white power in that place and time made you a target.) And she may not have boarded that particular bus, on that particular day, intending to get arrested. But Parks also knew what she was doing. Sure, she was a seamstress, one widely known and respected in Montgomery’s black community. But as secretary of the local NAACP chapter, Parks also was deeply involved in a movement to reform the city’s draconian segregation laws—one primed for action thanks to a then 15-year-old girl named Claudette Colvin.

Colvin was a smart and rebellious teen whose family lived in King Hill, a small, poor section of town flanked by white neighborhoods. She became politically active in high school after her classmate Jeremiah Reeves was accused of raping a white woman. Reeves confessed to the crime, and an all-white jury convicted the boy and sentenced him to death. Reeves later recanted, saying the police had forced him to confess. The case was appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which ordered a retrial, but the outcome was the same.

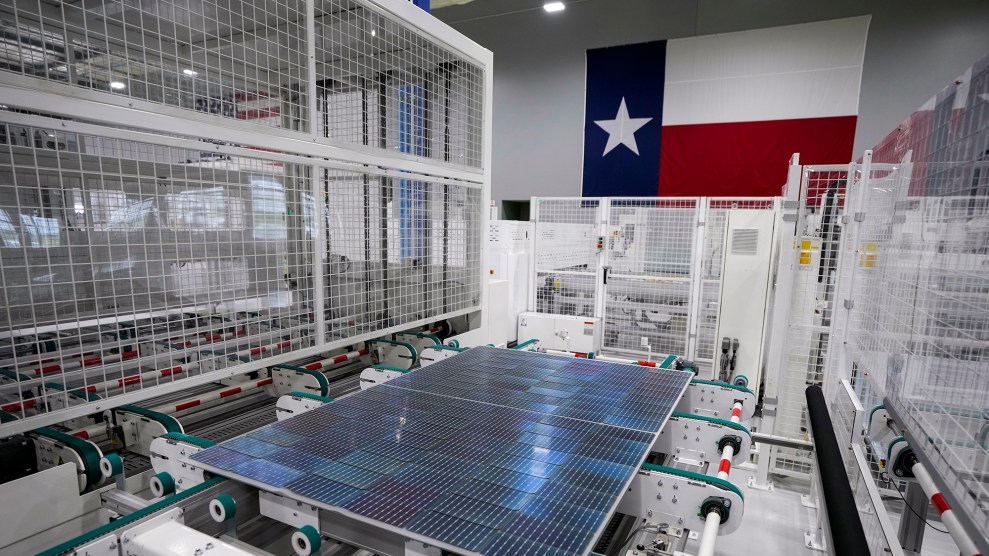

On March 2, 1955, a full nine months before Rosa Parks took her famous stand, Colvin boarded a city bus with her friends, taking a seat behind the first five rows, which were reserved for whites. Although the practice was illegal, drivers would routinely clear whole rows to accommodate a white rider if the white section was full—even if it meant those black riders would have to stand.

That’s what happened that day. When the driver shouted, “I need those seats!” Colvin’s friends dutifully moved to the back, but she stayed put. The driver chewed her out, to no avail. A couple of stops later, city police were there to meet the bus. Still Colvin refused to leave her seat. “It’s my constitutional right!” she shrieked again and again as the police dragged her from the bus.

This was nothing like Rosa Parks’ quiet arrest later. (Parks was neither handcuffed nor jailed, and was released after being found guilty of disorderly conduct and paying a ten dollar fine.) Somehow one of the cops got scratched in Colvin fracas, and the girl was charged with resisting arrest and assaulting a police officer in addition to breaking the city’s segregation law. On the ride to the station, Colvin told author Hoose, the police called her a “nigger bitch,” and took turns trying to guess her bra size. When she arrived, other officers called her “thing” and “whore.” After booking, she was thrown in the city’s adult jail.

The news traveled fast, and the black community was livid. Black leaders were already engaged in fruitless talks with the city and the bus company to gain better accommodations, and boycott was in the air. NAACP leaders recruited a sharp young lawyer named Fred Gray, who would argue that the bus company was breaking the law by asking people to give up a seat when no other seats were available. Shortly before Colvin’s trial, Montgomery NAACP boss E.D. Dixon called up Rosa Parks, who also headed the NAACP’s youth group. Recruiting Colvin, he told her, might help get more young people interested in the movement. Parks obliged, and soon became friendly with Colvin.

On her day in court, Colvin was found guilty of all charges by a hostile judge. The verdict, as one movement leader recalled, “was a bombshell.” The people were ready for action. But local black leaders debated whether Colvin was right for the part. They needed the whole community on board for a boycott to work. Colvin was just a girl.

They held off on calling for a boycott, and instead raised money for her appeal. In Montgomery Circuit Court, three months after Colvin’s arrest, a judge dismissed charges of breaking the segregation law and resisting arrest, but left the assault charge intact. It was a diabolically clever move: Now Colvin had a serious police record that could harm her future, but she could no longer appeal to challenge the Jim Crow regulations.

Colvin told Hoose that when she returned to school after the loss, the kids ridiculed her, and mocked her line about constitutional rights. What’s more, around that time the vulnerable teen—who also had recently lost a sister to illness—was taken advantage of by a man a decade older. She became pregnant, further contributing to the ostracism she faced.

But Colvin made her mark on the minds of others. When Rosa Parks boarded the bus that fateful day and refused to relinquish her seat, it wasn’t that she was simply tired; she was sick and tired—and inspired in no small part by her rebellious protégé. She acted knowing full well what she was about to unleash.

Although few remember Colvin’s name, it was she who may have had the most clout in the final tally. As the Montgomery Boycott matured, police and city leaders were getting more and more effective at harassing the carpool riders and the movements’ leaders, of whom scores were indicted. Martin Luther King Jr., a recent arrival from Atlanta who had fallen into the role of spiritual leader for the city’s anti-segregation movement, was in deep trouble. Found guilty of organizing an illegal boycott by the same judge who had presided over Colvin’s appeal, he was fined and sentenced to a year of prison labor.

And that’s when another verdict came down. The saving grace. Some time after Colvin’s defeat, and the birth of her baby, lawyer Fred Gray had taken the city to trial in federal court, this time in a lawsuit intended to quash segregation altogether in the city bus system. Among the plaintiffs—and she turned out to be the most powerful witness—was Claudette Colvin. In a 2-1 vote, the three-judge panel ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, spelling the beginning of the end of segregation in Montgomery.

As Hoose reveals in a book part history, part oral history, and entirely accessible to young people, it pays to look beyond those few pages in a dog-eared history text.