—By Ben Dooley | May/June 2014 Issue

Two days after Barack Obama won reelection, I met a young Chinese woman, whom I will call Anne, in the basement café at the San Francisco Public Library. Anne worked part time and gave a large portion of her earnings to a group she called “the Community,” a Christian sect led by a charismatic Korean pastor named David Jang. After joining the group in her late teens, Anne had spent more than seven years working in its ministries—organizations and businesses run by Jang’s disciples. With short hair and large glasses, Anne was now in her late 20s but looked younger. She said she rarely had enough money for small luxuries like coffee. We chatted with a mutual friend while we waited for her husband, Caleb, who also worked for a ministry: the International Business Times, the flagship publication of an eponymous online news company that would, nine months later, become the new owner of Newsweek magazine.

Caleb was running late because he was translating Obama’s victory speech into Chinese for IBT, which publishes 11 editions in seven languages. When he arrived, he shook my hand and, without meeting my eyes, sat beside his wife. “Tell him,” she said, pushing her husband’s elbow and raising her chin in my direction. They argued under their breath in a few clipped, Chinese sentences, and then he turned to me and said, “We’re working here illegally.”

For the last year and a half, Caleb said, he and Anne had worked at Community ministries while living in San Francisco on visas they received for Caleb to attend Olivet University, a small Bible college Jang founded in 2004. Caleb was enrolled at Olivet, but he rarely had time to study. Instead, he told me, he translated articles from English into Chinese for 10 to 12 hours each weekday, and commonly worked weekends.

“The pay isn’t bad,” Caleb said, as though daring himself to be wrong.

I asked him how much he was making. He told me between $500—their part of the rent for the group home they shared with 8 to 10 other Community members—and $1,000, depending on the month. I did a quick calculation of what he’d earn working full time at California’s minimum wage. I wrote the sum, $1,280, on a napkin and slid it across the table. His hand trembled as he picked it up. He and Anne looked at each other. “That doesn’t include overtime,” I said.

People like Caleb and Anne helped IBT, founded in 2006, become one of the world’s largest online news sources, a network of websites whose media kit claims 40 million unique visitors each month. In August 2013, IBT bought Newsweek from Barry Diller at the low point of the once-venerable title’s long decline. Departing editor Tina Brown’s controversial covers and attempts at synergy with the Daily Beast had failed to shore up the 80-year-old magazine’s finances; it published what was supposed to be its final print issue at the end of 2012.

But within months of the IBT deal, Newsweek‘s new editor in chief, Jim Impoco (formerly of the New York Times, Portfolio, and Reuters), said it would be back on newsstands in the first quarter of 2014. Under IBT’s ownership, Impoco has attracted an experienced and well-respected crew of journalists, and on March 4, IBT also announced that Peter Goodman, an award-winning former New York Times economics correspondent and business editor at the Huffington Post, would take over as IBT’s editor in chief. Two days later, Newsweek returned to print with a splash, alleging—to much acclaim and debate—that it had identified the mysterious creator of the electronic currency bitcoin.

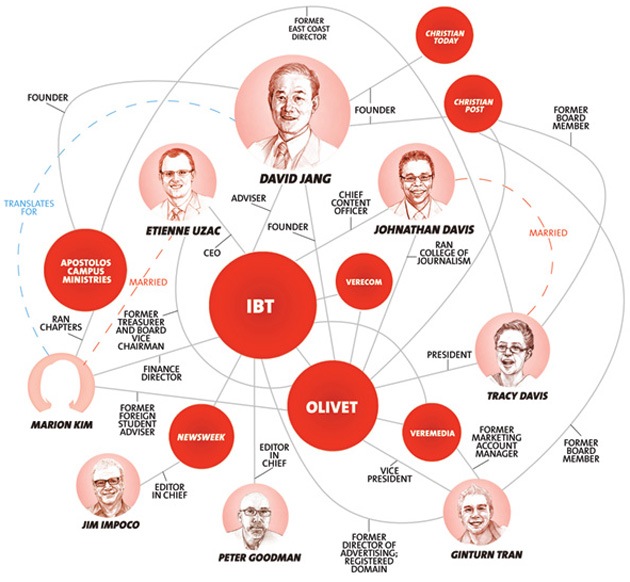

At the time of Newsweek‘s sale, Christianity Today and BuzzFeed published reports claiming that IBT had ties to Jang and the Community. Etienne Uzac and Johnathan Davis—IBT’s CEO and chief content officer, respectively—told BuzzFeed‘s Peter Lauria that IBT has an ongoing relationship with Olivet, but claimed that it was akin to the connection between Silicon Valley and Stanford. “That’s as far as it goes,” Davis told Lauria. On March 2, in a New York Times article about Newsweek‘s return to print, Davis and Uzac again denied IBT had formal ties to Jang. They dismissed similar questions from the Guardian (which reported that Davis, in a Facebook post, had endorsed the view that gay people can be “cured”) last week.

But the connections between IBT and Jang’s Community, a Mother Jones investigation has found, go much further than Davis and Uzac have acknowledged. Thousands of pages of public records and internal documents—ranging from emails to budgets and strategic plans—and interviews with more than a dozen former IBT employees and members of Jang’s inner circle make clear that:

- Olivet and IBT are linked to a web of dozens of churches, nonprofits, and corporations around the world that Jang has founded, influenced, or controlled, with money from Community members and profitable ministries helping to cover the costs of money-losing ministries and Jang’s expenses. Money from other Community-affiliated organizations also helped fund IBT’s early growth.

- Olivet students in the United States on international student visas say they worked for IBT and other Community media entities, sometimes for as little as $125 a week. Both Olivet and IBT described these positions as internships, and said no-one was allowed to work illegally. Several students I spoke with say they were not told they were interns, and documents from Olivet and the businesses list students as reporters, editors, and salespeople.

- According to the Times, Uzac and Davis “said Jang had no financial stake in IBT or influence on the business.” But the pair acknowledged to Mother Jones that Jang has provided “advice” to IBT. And while there’s no evidence Jang controlled editorial matters, internal documents show him routinely weighing in on a wide range of business decisions, from personnel and business strategy to typography.

- Jang sees Community-affiliated media organizations, including IBT, as an essential part of his mission to build the kingdom of God on Earth. He has said that media companies affiliated with the Community are part of a new Noah’s ark designed to save the world from a biblical flood of information.

I tried to reach Jang through Olivet, which he founded, and two other organizations he still officially leads. A Mother Jones reporter also visited an Olivet satellite campus in downtown Manhattan where Jang preaches to deliver written questions, but Jang never responded. I repeatedly sought to interview Uzac, Davis, or other IBT representatives and sent detailed questions to both men and their PR representative, who replied that IBT would not respond in detail and that the questions were “formed by unethical sources that have been demonstrated in the past to falsify information.” IBT offered an official statement, reiterating that Davis (31) and Uzac (30) alone founded and own the company, and saying IBT was “grateful” for help from an internship program with Olivet. “Any claims that we are engaged in activities with organizations that go beyond what is commonly recognized as appropriate and ethical behavior are categorically false,” the statement reads. “Furthermore, our conduct with partners is compliant with all applicable laws.”

IBT is hardly the first media company with close ties to a religious group. The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church founded the Washington Times; the Christian Science Church has published the Christian Science Monitor for decades. But while those affiliations are formal and public, IBT’s ties to the Community are neither. In one email, Davis went so far as to refer to his Community role as “inherently covert.”

There’s nothing unusual about business leaders associating with people or institutions that share their values. And Impoco seems satisfied that his editorial operations are walled off from his bosses’ religious affiliation. “The notion that this is a Christian company is ludicrous. I don’t think about [Uzac and Davis] being Christians any more than I used to think about Mort Zuckerman being Jewish,” says Impoco, who worked for Zuckerman at US News.

So why have Uzac and Davis been so eager to downplay their ties to Jang?

In the summer of 2005, a young woman stopped Anne near her college campus in southeast China and asked if she’d found Jesus.

“The first time I heard the Bible, I cried,” Anne told me later. The missionary belonged to Apostolos Campus Ministries, a Christian evangelizing group Jang founded in the early ’90s. Anne began attending off-campus Bible study twice a day. Before long, her tutor told her she was ready to become an evangelist herself. Anne was sent to a nearby college, where she led Bible study sessions in a house close to campus. She soon found herself devoting nine hours a day to Apostolos: three hours of Bible study, three hours of evangelizing, and three hours of praying. The 3-3-3 practice, another former member told me, is an expectation throughout the Community that leaves little time for anything else. It makes you “malleable,” she said.

Anne dropped out of school and, at the direction of a group leader, moved to Beijing to recruit other students into the Community. She shared a small house with members of Apostolos and another group that Jang founded, Young Disciples of Jesus. None of the evangelists in Anne’s house had jobs, she told me. To survive, they borrowed money from their friends and families. When those funds dried up, Anne decided to apply for a bank loan, telling the loan officer that she needed it to pay her college tuition. She gave the money to Apostolos, then asked her parents to help pay off the loan. “I was a good girl then,” she said, “so they believed me.”

As a new member, Anne started with “basic” Bible study focused on traditional Christian concepts. But as the courses progressed, Jang’s name popped up with increasing frequency. Parables related by the pastor appeared side by side with the teachings of Jesus and other biblical characters. “We listened to him a lot,” she told me. “We memorized the articles.”

The lessons all seemed to lead toward some larger revelation. After completing the final reading, another former member told me, her tutor drew a question mark on the page and asked in a whisper, “Do you know who is the Second Coming Christ?” She hesitated for a moment before responding, “Pastor David.” “They make you confess it,” she told me, “like Peter did to Jesus Christ.” The secret of Jang’s true identity, she was told, must be protected because nonbelievers would “kill the Second Coming Lord as they did the first one.”

Susan Chua, another former Community member, gave me a similar account. Indeed, every ex-Community member I spoke to either said they believed Jang was the Second Coming or said they were aware that others believed it. But Jang himself has repeatedly denied that he is the Second Coming and discouraged his followers from using the term. Several investigations by the heresy committee of the Christian Council of Korea concluded there was “no evidence” to indicate that he had made such claims, and in 2009, a Korean court sanctioned a newspaper for saying that Young Disciples taught that Jang was the Second Coming. In the Times, Davis and Uzac vigorously dismissed the idea that they considered Jang the Messiah.

I asked Anne whether she ever heard anyone in the Community publicly refer to Jang as Christ. “No one said directly,” she replied. “But I think he was. Just like I ask you, ‘Two plus two equals?’ The answer is four. They only said, ‘Two plus two.’ No one said four directly.” Back then, did she believe it was true? “Yes,” she said. “With all my heart.”

Born JaeHyung Jang in 1949 to a conservative Christian family, Jang came of age during the Korean War. As a child, he often retreated to the mountains near his home, where he spent long hours praying. On one such occasion, Jang recalled during a Bible study session in San Francisco in February 2005, he looked up to find a young man who looked much like himself on his knees beside him. “I had this kind of trembling feeling,” Jang said, according to a transcript of the event. “As I’m praying, I am looking at myself praying. This is the supernatural power. I came out of myself, and I can see myself.”

Soon, such out-of-body experiences became a regular occurrence. Sitting in church, Jang said, he seemed to float above the congregation, looking down on the congregants as the pastor spoke: “I would be on my knees and my spirit would just go up. My head would hit the ceiling.” He became fascinated by the Rapture—the idea that, during the end of days, God will whisk true believers away while sinners are left on Earth to suffer. Once, while other children played at recess, Jang stood watching a balloon float into the sky and wondered if he, too, would one day float up to heaven. But around the time he founded the Community in 1992, his views shifted. Christians, he has said, should not focus on their reward in heaven; instead, they should work to create heaven on Earth, building institutions that will remake the world in the image of the church.

Now 64, Jang has a kind face, with perpetually bemused eyes and a thick, dark head of meticulously coiffed hair. He often preaches in a discursive stream of consciousness he once described as “random talk.” When I asked former Community members why they were drawn to him, they often seemed stumped, as if I had asked a particularly stupid question. “It was how everyone else reacted to him,” one woman told me. “When you see all of these very humble missionaries, who dedicated their lives to God, go up to him after services, wanting him to bless their babies, it makes him seem very holy.”

Jang also has a history with Moon’s Unification Church. In 2013, a Japanese court resolved an almost six-year-long libel case that Christian Today, a Jang-founded website, filed against Makoto Yamaya, a Salvation Army major. Yamaya had claimed the Community was part of the Unification Church and that Christian Today had mind-controlled its employees; the court found that these charges had no basis. But it also found that Jang joined a Unification Church student group as a young man, eventually rising to the rank of executive director of another church-affiliated student organization. He then went on to a church-run theological institute, and helped manage the transition when it became Sun Moon University in 1993, subsequently leaving the church. Four former members tell me that Jang often spoke of his time in Moon’s church, including his marriage by Moon in a 1975 mass wedding, an event also affirmed by the Japanese court.

Jang now rejects the Unification Church. “They pray in their leader’s name,” he told followers in 2008. “They went wrong and went astray because they threw away Jesus and threw away the cross.”

Moon once vowed the Washington Times would “become the instrument in spreading the truth about God to the world.” But Jang’s interest in the media business stems from a vision of a new biblical deluge. The world has entered the period of a second flood, Jang explained to his followers in a 2002 message about Christian Today (not to be confused with Christianity Today, the evangelical Christian magazine founded by Billy Graham, which infuriated Community leaders when it ran a multipart exposé about the group). But instead of the rain that bedeviled Noah, Jang explained, humanity is being drowned in information. Information, he said, is everywhere, but “there is no water to drink.”

To solve that problem, Jang explained, the Community would build a new ark—a group of true believers that would gather up the people of the world and prepare them to enter the kingdom of God. This new ark would be divided into three types of ministries, representing the spirit, the soul, and the body of the church. The spiritual ministries are devoted to Bible instruction and include Apostolos and Young Disciples. Olivet represents the Community’s soul. The group’s moneymakers—businesses ranging from a shoe store to a web design firm—make up the ark’s body.

The media operations were hybrids. Community members would create “righteous media to spread the words of God in this era,” Jang said in 2002: business in the front, soul in the back. The Community’s first two media ventures, Christian Today and Christian Post, were explicitly religious. But when IBT was founded in 2006, it was with a secular focus on the globalizing world of business.

Still, Jang’s sermons make it clear that he views all of the Community’s enterprises as serving the same overall purpose: “We are one, but we are also independent at the same time,” he said in 2009. “Church as church, company as company, organizations as organizations. But we are all going forward toward the [kingdom of God], and the service in the heaven will be like this. The whole bodies covered with eyes, crying, ‘Holy, holy, holy.'”

Jang’s expectations for IBT were high. On Easter in 2006, at the company’s dedication service in New York City, he expressed his hopes for the firm’s future: “Through IBTimes, truly unimaginable, many things will happen. Much blessings will pour down on us.”

Although IBT carefully avoided public association with the Community, behind the scenes the connections were clear. In December 2005, Verecom, a Community-affiliated web design company, trademarked the name International Business Times. The trademark application listed the email address of Ginturn Nathaneal Tran, who would go on to be the vice president of Olivet University. The filing address on the trademark application—631 Howard St., San Francisco, CA—was the same as Olivet’s. Tran also registered IBT’s domain name, ibtimes.com, from the same address. (When asked about the coincidence, Olivet president Tracy Davis, wife of IBT’s Johnathan Davis, said, “That’s a multifloored building.”)

Community members were asked to help the new company succeed. Newsletters distributed in February and March 2006, soon after IBT’s domain was registered, instructed members to pray for the company to make “one billion dollars this year.” A list of prayer topics shared among members in April 2006 urged them to “Click constantly!” on IBT’s various websites.

Johnathan Davis and Etienne Uzac were obvious choices to run a Community-affiliated media company. Both had solid credentials—Uzac, who became the company’s CEO, graduated from the London School of Economics, and Davis, who became the COO (he also served as executive editor and is now the chief content officer), had studied engineering at the University of California-Los Angeles and worked at two tech companies, S3 Graphics and NVIDIA.

The two men also had deep ties to the Community. Uzac had written for the Community’s internal news service, Verenet, which disseminates Jang’s sermons and other Community news. He is married to Marion Kim, Jang’s occasional translator, who has held a series of important posts at Community-affiliated institutions. After studying abroad in South Korea in 2000, Kim managed Apostolos programs at the University of California-San Diego, Columbia, and UCLA. She was Olivet’s foreign student adviser when it first opened, received a master’s in divinity from the school, and later served as IBT’s finance director. Davis, in addition to being married to Olivet’s Tracy Davis (who has also served as East Coast director of Apostolos), holds a graduate degree from the university and served as the head of its school of journalism.

In the Times piece about Newsweek‘s relaunch, Uzac and Davis told a classic lone-entrepreneur story of “scraping together money from family and friends” to start their website. But documents, archived web pages, and interviews with former Community members tell a more complicated tale. When I read Uzac and Davis’ account of IBT’s origins to a former member who was involved in the company’s founding, he guffawed. “That’s completely false,” he said. IBT “was founded because Olivet University had just been started and it really needed money. [Jang] founded it by basically choosing some members of his church who had proved their business savvy. They had these chats, and basically David Jang laid out the whole vision for the company. I assume Etienne [Uzac] was chosen because he was pretty qualified.”

A former Community member who lived with Uzac for a time told me a similar story in an email: IBT “was [Jang’s] idea, just like all the other ministries/businesses involved with the church. Etienne was brought over from England to New York to head IBTimes. Etienne was named ‘founder’ of IBTimes after the fact.”

Another member close to Jang said much the same. “It was an idea of Jang to make IBT, that’s for sure. But he needs people who do it, so he assigns people and they do it and Jang controls everything and changes if he doesn’t like [it].”

Davis and Uzac’s public statements about the early history of IBT are also contradicted by internal documents. In January 2006, an article from Verenet reported that Uzac had received a commission from Jang to lead an unnamed “e-business.” “Along with the appointment of leader Etienne, several personnel changes were made in step with Pastor’s recent focus on the financial ministry in U.K.,” the article continues. It goes on to quote Uzac on his new role: “The outcome has already been determined by God, it is about how fast my faith can be strongly set up.”

A former member provided me with a formal photograph taken during IBT’s inauguration ceremony. Davis stands in the third row, eagerly peeking his head out as if trying to be seen. Jang and Uzac are seated front and center with Andrew Lin—then the chairman of Olivet University.

In March 2006—three months after Verecom trademarked IBT’s name and weeks after the Community began urging its members to pray for the company’s success—Uzac filed IBT’s articles of incorporation in New York. Davis’ name is nowhere on that document, and an early version of IBT’s masthead indicates that Uzac founded the company with a man named Kosugi Naohiro, not Davis. Naohiro’s name also appears on the articles of incorporation for the company that operated IBT’S Japanese website. Jang ordained Naohiro as a pastor in September 2004, according to a program for the ceremony submitted as evidence in the Japanese libel case.

The same day Uzac incorporated IBT, local versions of IBT were set up in Australia and the United Kingdom, with neither Uzac nor Davis listed in the filings. The foreign editions shared the same layout as the US version, and published many of the same stories. Andrew Clark, the man who registered IBT in the United Kingdom, had registered Olivet’s UK campus in 2006. Ting Ting Xue, who registered IBT in Australia, was the executive director of Apostolos Campus Ministries for East Asia and Oceania.

Jang continued to influence IBT after its founding. Internal emails and documents show Davis, Uzac, and other IBT managers discussing instructions from PD—the Community’s internal abbreviation for “Pastor David”—about how to run the business. IBT emails are rife with phrases such as “I asked PD,” “check with PD,” and “PD told me.” In one such email, an IBT employee relays a transcript of a meeting in which Jang expressed his disdain for the site’s layout: “Who designed this? The logo should be in the middle. I wish it was a thicker font like Gothic.”

Jang advised Uzac and Davis on a range of issues, from which ads to run to the payment terms for advertisers and even their specific work responsibilities. In a 2009 email titled “what PD said,” Kim told her husband, Uzac, that Jang “said to not rush to get clients [to] close deals but to wait for them and go along with how they want to pay.” (Kim says she never relayed such instructions.) In another email, Uzac wrote about “preparing a report for dr. jang.” In another 2009 email, Davis wrote that Jang “told me to stop doing sales and start focusing on editorial again.”

In 2010, Davis was among the recipients of several planning emails for a gathering of Community leaders. In one, leaders and representatives of Community business ministries were asked to prepare reports about their companies, focusing on “Mission,” “Media,” “Business,” “Design,” and “IT.” “It would also be good if reports can be typed and printed and submitted to PD beforehand,” the email read. “If reports are prepared well and presentation is polished to 30 min, I think PD would want to hear them all in succession.”

In the years after IBT’s launch, the Community continued to expand. In October 2009, Jang claimed in a sermon that the group had 1,400 web domains, connecting CEOs, missionaries, and students in a vast network on which they could listen to webcasts of Jang’s teachings one day and discuss their ministries’ financial arrangements the next. The Community’s ark, in Jang’s words, was “coated in pitch” and ready to sail. There was just one problem: money.

Despite Jang’s hopes, IBT didn’t immediately rain down blessings. Internal documents show that when IBT was low on cash, it would receive injections from other Community-affiliated organizations. A 2006 news item from Verenet titled “The Servitude of Veremedia” brags that “over 95%” of all revenue at Veremedia, a Community-affiliated ad agency, “goes to supporting missions and other ministries, including…IBT.”

This money wasn’t simply payments for ads Veremedia sold for IBT, the article explains. “Veremedia has begun selling for companies outside of our own ministries,” it continues. “Revenue generated from these sales is used to support IBTimes until the sales agencies begin to bring in large advertising deals.”

Internal Veremedia emails tell a similar story. “By grace of God, PD gave us honor to help…IBTimes and other ministries,” Sophia Yu, Veremedia’s accounting manager, wrote in an October 2007 email. “Soon, we will know that money we spent to help other ministries were truly put to good purpose. It’s all used to build our kingdom that we will live in. I am really thankful that God chose our team to be used in that way.”

Veremedia and other Community ministries didn’t always come through. In November 2009, the First Bank of Missouri sued IBT and Verecom, the Community-affiliated web design firm, for more than $113,000 in back rent and associated fees. When the companies didn’t pay, the bank went after their guarantor: Olivet. The parties settled out of court. Olivet guaranteed Verecom and IBT’s debt because it saw “an opportunity to get an internship program with this company in a way that was very affordable to the school,” Olivet President Tracy Davis said in an interview.

Two former IBT employees told me that the company’s payroll was sometimes behind schedule and employees were frequently scrambling for cash. Yet despite its financial struggles, IBT made donations to other Community entities. In the fourth quarter of 2008, according to internal budget documents, IBT donated more than $10,000 to Olivet’s San Francisco and New York City campuses, and tithed $6,400 to the Olivet Center for World Mission, which three former members told me was an internal unit of the Community that also handled Jang’s expenses. The same documents indicate that during this period, IBT was behind on the $20,000-per-month rent on its New York office. (Tracy Davis acknowledged IBT had made donations to Olivet in the past, and said the Olivet Center was started by Olivet alumni and focuses on missionary work abroad.)

IBT wasn’t the only Community-affiliated business sending money to the Olivet Center. A 2007 annual balance sheet for Veremedia shows $53,444.04 of donations to it. Occasionally funds appear to have been given to Jang himself. “When PD comes, we will give him tithe about $2k to him directly,” Yu, Veremedia’s accounting manager, said in the October email.

Though Jang did not lead a lavish lifestyle, the Community also struggled to finance his expenses. A November 2009 message outlining various financial shortfalls and asking for donations lists $50,000 for Jang’s son’s wedding among the outstanding debts. In March 2010, a senior Community leader wrote that a Korean Community leader had phoned to express her frustration with the group for allowing Pastor David to get behind on his car payments.

In the fall of 2010, Uzac sent an email from his IBT account to Davis and other senior IBT employees. Olivet’s extension campus in Kirkwood, New York, he wrote, owed $9,000 to various creditors. A check to one of them had bounced.

IBT had just $4,200 left in its Citibank account, Uzac warned—and that was only thanks “to the return of a blank check we gave to OU. So we put that in OU NY account along with 2.2k left in our Chase, ran to Chase deposited everything, so OU NY had enough money to get that check force paid. The branch manager was very angry at Ruth as she did the same thing yesterday for another check.”

IBT was always publishing “slideshows of Miss America winners and things like that,” one former employee told me. “As a journalist, it was just an incredibly demoralizing place to work.” Management, another former employee told me, issued “impossible” demands for ad sales and content—in one month, they were to increase revenue by millions of dollars, a minimum of 10,000 hits per article—and fired those who couldn’t deliver. In late 2011 and early 2012, IBT brought on an entirely new sales team, four former employees told me, and then sacked them all in March 2012, without severance or explanation.

The constant demand for clickbait meant that staffers spent much of their time rewriting and aggregating stories from other sites. It’s a common practice, but at IBT the pressure led, in at least one instance, to a major ethical lapse. In the summer of 2010, Japan’s largest newspaper, the Yomiuri Shimbun, reported that of the 432 articles IBT’s Japan edition published between July 1 and August 19, 302 were created by copying sentences from Japanese newspapers, wire services, and broadcasters and combining them, collage-style, to create seemingly new stories. The company’s Japanese CEO apologized for the incident, blaming it on a contract employee.

Many early IBT employees were Community members, and low salaries were sometimes supplemented by rent and food subsidies. IBT financials from this period list “housing” and “living expenses,” as well as “tithe” to the Olivet Center, among the company’s expenses. In December 2008, for example, total salaries, living expenses, and commissions for IBT’s employees in New York and San Francisco (at least 18, according to a staff photo from this time) are shown as $11,743, with another $1,834 in tithe to the center.

In March 2010, Johnathan Davis wrote to Veremedia, the Community-affiliated ad agency, to beg for money to pay IBT workers who lived with their small children on Treasure Island, a community in the San Francisco Bay. Staffers normally commuted by bus to the company’s downtown office, where they could eat at Olivet’s Student Union, but with cash running short, Davis said with palpable concern, they couldn’t afford the fare. His correspondent noted that people at other ministries were being paid sporadically too, asking, “Will they starve?”

One day, about three years after Anne joined the Community, her pastor asked if she wanted a job. “My pastor said, ‘We have this ministry, we have that ministry. We have this company, we have that company. Who wants to go to this company? I can recommend you.'” She asked to be sent to IBT, where she hoped to learn more about journalism. She met Caleb while working for IBT in China, and the following year the couple flew to Korea, where Jang bestowed his blessing on them and 11 other couples.

A little more than a year later, Anne and Caleb applied for F-1 student visas so they could move to the United States and attend Olivet. This was not an uncommon trajectory for Olivet students. One, who remembers the experience fondly, said that among Jang’s followers in China, Olivet was seen as a place where people could “worship God and learn the words of God in a free country…In addition, they enjoy the free housing, free meals, and free course study. What a miracle! They call the campus heaven!”

Caleb received his F-1 visa without much difficulty, but Anne failed the interview for hers, and instead received an F-2 visa, which is given to the spouses and dependents of F-1 student visa holders. In March 2011, the couple moved to San Francisco, where Caleb continued working for IBT, and Anne found a job on Olivet’s campus.

That, too, wasn’t unusual: Every former member I spoke with told me that all of Olivet’s students and their spouses, regardless of visa status, worked for the Community’s ministries in some capacity. In addition, Olivet documents list numerous students as holding positions at IBT, Christian Post, and other ministries. Seven former students I interviewed told me that they worked at ministries elsewhere in the United States while enrolled at Olivet in San Francisco; like Caleb, many of these people believed they were working illegally. Four of these students, including Caleb, worked at IBT.

The law governing F-1 visas allows students to work on-campus for 20 hours per week. They can also work off-campus as part of “practical training” in their field—but only with special permission from the school. A spokeswoman for US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) explains that while the rules are “broad, so as not to be restrictive,” work should be directly related to the student’s major area of study.

Olivet documents show that the school periodically sent out reminders urging students to ensure they complied with visa regulations, and Tracy Davis says that while compensation in these internships was left up to employers, no one was allowed to work illegally. She also says that in OU’s view, theology studies inform “all walks of life,” and students should not be “prohibited from any vocational internship.” OU says that it had an internship program with IBT for several years (during a period when Johnathan Davis served as both the head of Olivet’s journalism program and IBT’s executive editor). Tracy Davis says the IBT internship program ended two or three years ago.

Yet as recently as 2012, Olivet students were listed on IBT’s staff roster and emails in a variety of positions, from editors to sales and IT staff. Asked about six such individuals, Davis responded that “each of the individuals was, or is, either an intern or employee of IBT Media and satisfied relevant employment eligibility requirements including, where appropriate, visa requirements.” However, OU documents do not refer to students working at IBT as interns, and a number of former OU students I spoke to said the work was not characterized to them as an internship.

Jang also appears to have counted on Olivet students to help IBT. Notes taken during a March 2008 meeting with Jang and sent to IBT staffers record his suggestion that IBT leaders have Olivet students implement new features on the company’s site. “Give it to students at OU, and they’ll do it,” Jang said, according to the notes. The students, he said, should work in teams and compete to see “who will make it better and who makes…millions of unique visitors.”

Rules on how and where international students can work have historically been spottily enforced. In 2011, ICE did shut down a Bay Area Christian school, Tri-Valley University, for admitting F-1 students who held jobs while taking a few classes online. But according to a February report from the Government Accountability Office, Washington “has not consistently collected the information and developed the monitoring mechanisms needed to help ensure foreign students comply.”

But if there’s room for interpretation in the F-1 rules, the regulations for F-2 visa holders, such as Anne, are quite clear: They may not work, on campus or off—not even in unpaid internships. Yet Olivet officials appear to have instructed these visa holders to do just that. “If every single person attends all ESL classes and other major courses, we can’t really find enough workers for each ministry on campus,” Lydia An, an employee in Olivet’s finance office, wrote from her official Olivet account on January 2012. “We cannot let everyone on campus to focus on study only…We’ve came to a decision that F-2 students should focus on ministries more while F-1 students study in classes for 2011 winter quarter. Rooms and food will be provided free of charge as long as F-2 students work and maintain a certain work performance in a ministry.”

That makes no sense, says Anna Stepanova, an immigration lawyer who has worked on F-1 and F-2 visa cases: “There are no F-2 students,” she said. “They’re dependents. They accompany F-1 students. They’re not supposed to work.”

Tracy Davis says An’s email referred to cooperative child care. “This is an email that’s talking to married students in the context of family work and child rearing,” she said. “If you put the word ‘family’ in front of this word ‘work,’ it’s not talking about work where you get a W-2. It’s talking about family work and shared child care.”

Susan Chua, who says she was dispatched to the San Francisco offices of the Christian Post after coming to Olivet on an F-2 visa, says that doesn’t reflect what she was told. For believers like her, she says, working in the Community’s businesses was simply another way of serving the Lord. “Whether they came to US with F-1 or F-2 visas, the majority of them were devoted members to the community and their belief system. They were going to work extremely hard and sacrificially and obediently and joyfully for the building of the ark—the various ministries in the whole community.”

“There was no concept of pay at that time in the community,” Chua added. “You were feeling obligated to donate and contribute instead of receiving. The little money given by the ministry office you were working in was to cover bus fares and cheap meals in [Olivet’s] Student Union.”

Another former student told me, “The members suffer. They are young, naive, believe the teachings. After some time they find themselves without money, because they donated what they had. And they work basically for free…The visa thing and being far from home makes things more complicated.”

Not everyone working for Olivet—or IBT—was in a position to know about these practices. Although most Community-affiliated companies initially employed only Community members, by the end of 2010, IBT and Veremedia had begun hiring nonmembers. At one point, Veremedia marketing manager Sophia Yu wrote that she was worried the new hires would find out the company was hiring “illegal people,” since she knew it was a “crime.”

William Willis was hired as the part-time, advisory dean of the Olivet College of Journalism in 2008 by Johnathan Davis, then its director. For the first year of his affiliation with the school, Willis told me, he couldn’t get a student roster or a complete list of classes. “At times,” he wrote in a July 2009 email to a fellow faculty member, “it seems like most of the administrators there are—like me—in a part-time and advisory capacity, and that the place is almost being run by remote control. I can’t even get a full operating budget for the OCJ, of which I am listed as dean.”

When Willis finally did receive a budget, it was one sheet of paper with what he described as two “very large” numbers (he couldn’t recall what they were) written on it.

Public documents Olivet filed about its finances also provide a confusing picture. Documents submitted by the school to the IRS show total revenue, including donations, of a little more than $1.5 million in 2007. Yet in an annual report submitted by Olivet that same year to the Association of Biblical Higher Education, its accrediting agency, the university claims $9.7 million in total revenue for the same year. Donations accounted for $4.7 million of that amount. Tracy Davis says this is due to normal differences between 990 filings and internal financials. “For example, Stanford, which is also in Silicon Valley, has [a] huge difference between their 990 filings and their financials,” she said. She added that at Olivet, the difference was accounted for by “collaborative projects that we work on with partners,” as well as “operations, especially abroad, to support our online students.”

Ron Kroll, the director of ABHE’s accreditation commission, told me that the organization had investigated the matter and found that the school was “fulfilling its reporting requirements appropriately.”

Willis, for his part, was disquieted by the lack of transparency and came to feel that Olivet is “more shadows than substance.” When university officials, including Davis, ignored his repeated requests for more information, he took the issue to the school’s then-president, David Randolph. After an email received no response, “I went up to him and said, ‘Look, I need to know where this place is getting its money from,'” Willis told me.

“That’s a good question,” Randolph replied, according to Willis. “I never figured it out either.” (Randolph did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

With no answers forthcoming, Willis resigned. “As an educator,” he said, “I couldn’t in good conscience continue on. I felt the students that were drawn into the program weren’t being well served.” Olivet’s website continued to list him as a faculty member long after his departure, removing his name only after repeated requests. Journalism professor Bill Alnor was listed as the instructor for seven classes for nearly a full year after his death in March 2011.

Despite the multitude of businesses in its orbit, the Community was regularly short of money, former members told me. As recently as 2012, internal emails indicate that Olivet struggled to pay its rent and feared having its utilities shut off. Community members “borrowed” and “begged,” to help out, one source who worked as a reporter at IBT told me: “PD would explicitly or implicitly ask them to take money from their families.” Jang “told us to look into our parents’ eyes and ask them for money,” another member said.

Not even Uzac escaped the pressure. In January 2009, IBT was at least $100,000 in debt to various creditors. The company owed the Associated Press $33,000 and had lost its subscription to the news service, a serious obstacle to keeping the site’s firehose of content flowing.

During an emergency online conference with Jang and other members of IBT management to discuss the problem, Uzac offered to approach his grandparents for the money, according to a transcript. “Call them up today and ask them if you can borrow,” Jang wrote, in Korean, with Uzac’s wife, Marion Kim, translating. (Kim denies translating this exchange.) “You’re indebted against the office that Pastor made for you. This is shame,” he continued. “In the midst of such imp. battle, the ones who are sluggish and not working and quarreling won’t be forgiven from now on. Since it’s a challenge against our authority and power will be given a great punishment later and not use them again. Understand?”

By January 2013, Anne and Caleb had left San Francisco and returned to China. They were living in Beijing, and Caleb was working as a translator. Like other former members I interviewed, they saw the Community as being in decline.

But when news came, in August, of IBT’s purchase of Newsweek, that perception changed. Community members saw the deal as a potent sign of Jang’s power, and some former members I spoke to wondered if it meant his teachings might have merit after all. Suddenly, people who had agreed to speak to me on the record changed their mind.

Their concern was not unreasonable. The Community is litigious. “We have to punish them,” Jang said of his critics, according to the transcript of an August 2008 sermon in Korea. “We have many organizations so if they compensate, they should compensate a lot. After one is over, another organization will sue them again so all their lives they will be sued.” He has been true to his word: Community ministries have legally threatened or sued at least five people who have written about or come out against the group. And after Ted Olsen and Ken Smith (who provided me with some documents and introduced me to Susan Chua) wrote about Jang in Christianity Today, the Jang-founded Christian Post published a story headlined “Christianity Today Writer Ken Smith Is Founder of a Company Fined for Deceptive Business Practices; With Child Porn Ties.” The Post didn’t address Olsen and Smith’s claims about Jang in that story, and didn’t disclose the Post‘s association with the pastor. Instead, it targeted Smith, outlining how Zango, a company Smith cofounded, had produced software that some users later used to distribute pornography. Smith wrote that he took the article to imply that he was “all but a purveyor of child pornography.”

Today, most IBT employees are not members of the Community. As of February 2012, only around 20 of the 100 employees listed in the company’s US directory had worked for other Community-affiliated groups. Impoco and the rest of the Newsweek staff are accomplished career journalists with no ties to the Community’s religious endeavors.

“I’m satisfied that I’m stepping into a professional newsroom, and I’m simply not very interested in the personal beliefs of whom I’m working alongside or for,” Goodman, IBT’s new editor, told Mother Jones. “I can’t speak to [Uzac and Davis’] decision to discuss their faith or not discuss their faith, but I can tell you every conversation I’ve had with them since I met them has been about the journalism. There’s just been nothing unusual that caught my attention.”

We spoke on March 24, his first day on the job.

Additional reporting by Alex Park and Nick Baumann.