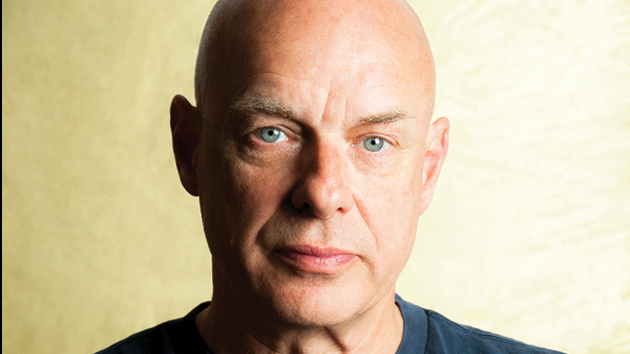

Photo: Michiko Nakao

BECAUSE SHORT, vowel-heavy nouns are in finite supply, the makers of crossword puzzles resort to familiar tricks: Charlie Chaplin’s fourth wife (OONA), Jacob’s hirsute brother (ESAU), Kwik-E-Mart’s manager (APU). Most of these people are known for exactly one thing, so the clues tend to be repetitive. ENO—that is, the 64-year-old British polymath Brian Peter George St. John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno—is an exception to the rule. All of the following crossword clues have been used to describe him: “Roxy Music co-founder”; “Ambient music pioneer”; “David Byrne collaborator“; “Grammy-winning Brian”; “Producer of Paul Simon’s newest album”; “Composer of The Lovely Bones‘ music”; “Creator of the ‘Microsoft sound’ played when Windows 95 starts”; “Brian who produced several U2 albums”; “Generative music pioneer.” (He has also helped chartbuster Coldplay hone its sound. “Brian doesn’t work with many people, so if he wants to work with you, you want to do it,” frontman Chris Martin told Pitchfork.) Some of his other epithets—abstract painter, inventor of iPad apps, subject of an eponymous song by the band MGMT—are too obscure even for crossword prodigies.

Eno makes his own music, too. His four experimental pop albums from the mid-1970s were universally revered and have influenced generations of indie rockers. But listeners began to stray—little surprise, since only one of his albums since 1977’s Before and After Science has included vocals. Bored with the rock format and intrigued by minimalist composers like Steve Reich and Terry Riley, Eno began to think less about melody and more about texture. He called his experiments “ambient” music—works intended for a particular place or to set a particular mood. With 1978’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports, Eno was not merely being cute; he’d recently visited the gleaming new terminal in Cologne, Germany, and thought it strange that the architects were so careful with their floor plan but had neglected to provide a soundtrack. (The album was later used for an Eno installation at LaGuardia.)

LUX, released in November, is Eno’s 17th album and his first solo album in seven years. “I’m sure somebody that doesn’t know my work well would think, ‘That sounds like another piece of clinky-clonk Brian Eno music,'” he told me when I interviewed him recently. “Actually, to me, it’s different.” Eno doesn’t call LUX an ambient album, but it evolved out of music commissioned specifically for the Great Gallery, a high-ceilinged hall in an 18th-century palace near Turin, Italy. The space is full of light—hence the title—but Eno lives in gloomy London and wrote the piece at home. When he went to the Great Gallery to preview his work, he thought it sounded too “interior,” so he revised it.

He was happy with the second attempt, as were the curators—for the next five years, visitors will hear LUX in the background—but he still didn’t think of it as an album. “I make a lot of pieces of music that I never release as CDs,” he says. “On my computer I’ve got, I think, 3,480 pieces of music that I’ve never released.” But he and his friends particularly enjoyed listening to LUX, and “I assume that if I really like something, I’m probably not that different from everybody else.”

I flew to North Carolina not long ago to watch Eno give a lecture. On the way, I listened to Music for Airports, and though it complements sleek European interiors better than it does the Asheville Regional Airport under renovation, it did have a slight narcotic effect. Eno came onstage at his event wearing stylishly muted colors, like a docent from the 23rd century.

The crowd greeted him with a standing ovation, which he received with unsmiling British reserve. He placed a transparency on a projector and wrote out the “menu” for the talk—”Riley/Reich” (as in Terry and Steve); “cellular automata”; “cybernetics”; “haircuts”—and then flitted among these topics with a graceful combination of whimsy and earnestness. (“Amateur art theorist” and “Thinks big thoughts” would also be accurate, if unhelpful, crossword clues.) He explicated a Danish town’s waterworks, projected a diagram of what Riley’s seminal minimalist composition “IN C” sounds like, and pithily defined culture (“everything you don’t have to do”) and haircuts (“a little artwork that everyone carries around on their head”).

But each of these thoughts led Eno back to his primary obsession, which he calls “generative art.” As he explained to me, if a regular piece of art is a finished product, a generative artwork is a process. A rudimentary example is a wind chime: Its maker chooses the tones, but the wind controls the melody. More complex systems, like Eno’s iPad generative-music app Scape, use computer algorithms to go on iterating indefinitely. In theory, it is a recipe for millions of pieces that no one will ever hear in full.

Eno has a clean-shaven head and a slightly grim expression, and he speaks in a mild Suffolk monotone. Witty and self-effacing, he refers to his albums as “little ships on an ocean of indifference,” and doesn’t mind if people use them as background music: “It doesn’t have to be right at the center of your world. It can be a sort of aesthetic cushion.”

Yet despite his modesty, Eno is calling for a radical revision of what it means to be an artist. Speaking in Asheville about “IN C,” wherein Riley lets the performers decide when to play each of 53 musical phrases, Eno said, “It gives you a different idea of what a composer is—rather different from that idea that we gather from the back of classical record covers, where Beethoven walks around with whole symphonies in his head and sits down and scribbles them out.” If traditional Western art criticism places the artist at the center of the story, Eno is more interested in how art is shaped by constraints and accidents. “We should think of composers,” he told me later, “as being more like gardeners than architects.”

The lecture coincided with a showing of Eno’s art installation “77 Million Paintings.” “I shall be spending a lot of my own time in there,” he promised, adding, “It’s very embarrassing to be an unashamed fan of your own work.” This is less immodest than it sounds: “77 Million Paintings” is a generative piece, so although Eno wrote the algorithm, he has seen little of the result.

The installation was in a dark room across town. There were low divans swathed in black drop cloths, illuminated cones on the floor, and, of course, generative music by Brian Eno; the low whistles, whooshing boomerangs, and distant chimes were so integral to the room you almost had to strain to hear them. The viewers were silent, their faces bathed in LED light, evoking a high-tech pagan temple during a solar transit.

I sat on the floor facing the “paintings”—13 screens, mostly rectangular, arrayed in a loose pinwheel. The central screen, synced to the cones on the floor, displayed a solid color that morphed gradually from violet to ultramarine to powder blue. By design, the colors changed imperceptibly slowly; you knew they were changing but could see it only by looking away. The other screens bore more-complex shapes and figures, also mutating slowly: a zigzag of vomity reds and browns; a kitsch yearbook-photo background with blue laser beams; a pink camouflage that looked like fatigues designed by Madonna; a white S on a field of flowers, like a bath mat at the Sheraton on Mars.

These were the paintings: the millions of permutations created by the changing screens. Most of them were unlovely. Every 20 minutes or so, I saw a combination that looked unusually well balanced. Four or five times over the course of three hours, there was something I’d consider hanging on my wall. I tried, and repeatedly failed, to avoid the intentional fallacy. I’d see a pattern that looked like Rothko, or Richter, or Miró, and think, “Ah, I get what he’s doing there.” But these weren’t allusions; they were accidents. Eno had made all of these paintings, but he had not made any one of them. If I were to ascribe cleverness to anything, it would be the blind eye of his algorithm.

Also see: “11 Killer Albums Brought to You by Brian Eno.” And click here for more music coverage from Mother Jones.