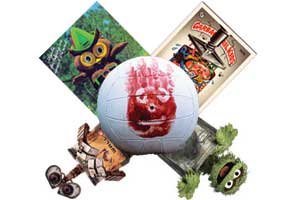

Photo: Chris Jordan

WHEN I PENNED The Green Consumer in 1990, I helped advance the notion that we could solve our planet’s environmental problems by making good purchasing choices. That we could, in other words, shop our way to environmental health. “By choosing carefully, you can have a positive impact on the environment without significantly compromising your way of life,” I wrote. “That’s what being a Green Consumer is all about.”

I fought the good fight. Twenty years later, I’m thinking of waving the white flag. Green consumerism, it seems, was one of those well-intended passing fancies, testament to Americans’ never-ending quest for simple, quick, and efficient solutions to complex problems.

Today, it’s become clear that good purchasing choices are relatively few and far between, in terms of products whose environmental benefits are both obvious and significant. True, there are green cleaners, organic socks, energy-efficient lightbulbs, and fuel-efficient cars, but such products are scarce compared with the tsunami of nongreen choices.

But there’s a deeper problem with green consumerism: It’s often hard to know which companies are improving their environmental performance—and how. The key element of making consumer choices—knowledge—is missing. Companies’ environmental improvements (or lack thereof) aren’t usually obvious, even to the experts. In fact, some of the most environmentally improved products make no green claims at all.

Here’s why: To save money, reduce risks, improve quality, and remain competitive, companies in nearly every sector are continually engineering waste, inefficiency, energy intensity, and toxicity out of their manufacturing and distribution. A few have upended their business models in the name of efficiency and enhanced productivity. They sometimes do this because of the reduced environmental impact, but mostly they do it because it makes good business sense—not something companies usually bother to tell their customers.

Simply put, waste represents things that a company bought, but that had no direct value to the customer. In other words, lost profit. Consider these examples of five companies that cut back—ultimately reducing what ended up in the landfill:

In 2006, Anheuser-Busch reduced the weight of its can lids by .002 ounces, saving 20 million pounds of aluminum annually—and the equivalent of the energy it takes to power 7,000 homes.

Thanks to a smaller box used for 250 million devices sold by Nokia during 2006 and 2007, the company saved $131 million in packaging and transportation.

Over the past 20 years, Procter & Gamble has reduced the weight of its Pampers diapers by as much as 40 percent (and some packaging by 80 percent) while improving their moisture retention.

Last year, General Motors vowed that by 2010, more than half its plants globally would send no waste to landfills. Already, 43 plants have achieved that status, where more than 96 percent of all waste is avoided or recycled; the remaining waste, such as wood from pallets, is incinerated, producing heat that is used to generate electricity.

Since 2007, McDonald’s has reduced the weight of its containers for the Big Mac, Filet-O-Fish, and Quarter Pounder With Cheese by 25 percent, while increasing their unbleached fiber content by 71 percent and recycled materials by 46 percent, saving an equivalent of 161,000 trees per year. The company has also made its 32-ounce polypropylene cup lighter, saving 650 tons of resin per year.

None of these companies qualifies as “green,” or perhaps even “good.” In most cases, the achievement in question represents a token percentage of the company’s resource use or waste. But they are achievements nonetheless—ones that because of the companies’ scale yield greater environmental benefits than many of the products hyped as explicitly green. Since these waste-reduction improvements are motivated by financial rather than ecological concerns, PR flacks don’t brag about them—but actually, they address an environmental problem that’s far graver than most of us realize.

Consider what I call “A Tale of Two Circles.” Perhaps you’ve seen the bottom circle, a pie chart containing nine slices, representing the composition of the stuff we throw out—a.k.a. municipal solid waste, or MSW. It shows that paper makes up about a third of our nation’s trash, while yard waste, food scraps, and plastics each represent about 12 percent. They are followed by smaller amounts of metals, rubber, textiles, leather, glass, wood, and other materials.

The MSW pie chart is well known in environmental circles and is the grist for a range of claims and disputes. The plastics industry, for example, uses it to “prove” that plastic bags are less of an environmental problem, at least a solid waste problem, than their paper counterparts. Aluminum, wood, and glass industries use it to make their own cases. Everyone, it seems, finds some solace in the numbers.

But there’s another circle—a much, much bigger one, totaling about 10 billion tons of waste a year, or roughly 40 times the MSW pie. This circle doesn’t have an official name—indeed, it’s virtually unknown in environmental circles, and the EPA doesn’t publish it. I’ve dubbed it gross national trash, or GNT.

The biggest slice of the GNT pie—76 percent—consists of industrial wastes from pulp and paper, iron and steel, stone, clay, glass, concrete, food processing, textiles, plastics, and chemical manufacturing; water treatment; and other industries—in other words, from fabricating, synthesizing, modeling, molding, extruding, welding, forging, distilling, purifying, refining, and otherwise concocting the finished and semifinished materials of our manufactured world. Included in this slice is industrial hazardous waste, a witches’ brew of toxic ingredients found in paints, pesticides, printing ink, and chemicals used in manufacturing processes—hundreds of such substances, from acetonitrile to ziram.

A slice of about 18 percent is something called “special waste,” a category of wastes defined under the US Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976. This includes waste from cement kilns, mining, fuel production, and processing of mineral components like uranium and phosphate. Along with 350 million tons of construction waste, these slices represent the everyday detritus of our world, the emissions, effluents, dregs, and debris created by industry. The government’s GNT tracking doesn’t even include all of the waste created by business and industry—it omits, for example, the billions of tons per year of US agricultural waste.

The thinnest slice of the pie—a minuscule 2.5 percent sliver of the whole—is municipal solid waste.

What’s the point? It’s only a matter of time before the story of GNT gets told and the public recognizes that for every pound of trash that ends up in municipal landfills, at least 40 more pounds are created upstream by industrial processes—and that a lot of this waste is far more dangerous to environmental and human health than our newspapers and grass clippings. At that point, the locus of concern could shift away from beverage containers, grocery bags, and the other mundane leftovers of daily life to what happens behind the scenes—the production, crating, storing, and shipping of the goods we buy and use.

And of course, so far I’ve been talking only about solid waste—the stuff that goes into landfills and other waste repositories. An even larger definition of waste could include nuclear waste, greenhouse gases, and, for that matter, any form of pollution in the air, land, or water. Each of these represents an inefficiency—the remnants of a product or process that had no value to the company. Indeed, in many cases (but certainly not all), the company had to pay to get rid of it. And we consumers pay for this stuff, too—literally and figuratively, since it both increases the product price and takes up space in our landfills.

All of this adds complexity for shoppers, activists, and policymakers. Should we focus on the environmental marketing claims of individual products (waste related and otherwise), or can we have a greater impact by setting our sights on companies that are reducing their contribution to GNT, even though these companies’ products may not be marketed as green? Is there even any easy way to identify these companies?

Truth is, there’s no reliable way of judging the environmental commitments of companies—all companies, not just the ecogroovy brands we know and love. Ecolabels, activist watchdogs, and governmental regulatory schemes can’t tell us. They focus on what is in the product, but not on the upstream activities involved in producing it.

There is one positive trend. A number of companies are creating scorecards that analyze the environmental attributes of their products with the aim of using this information to make gradual, systematic improvements. Since 2001, for example, SC Johnson, maker of Drano, Fantastik, Glade, Off!, Pledge, and Raid, has used a system called Greenlist to rate raw materials based on their environmental and health impact. Each product receives an overall score based on its composition, and the company tries to improve those scores every year. Greenlist has since been called the gold standard of toxics reduction efforts by environmentalists. Other corporate scorecards measure the energy, materials, water, or greenhouse gases associated with their products’ sourcing, manufacture, and use.

That’s encouraging, though the information typically isn’t available to the public. But that could change if consumers started demanding accountability and transparency of their purchases beyond mere green PR. Absent good information and standards, not only are consumers frustrated, but companies fail to understand their environmental impacts—and how to reduce them.

Indeed, our purchases of green-labeled goods may be lulling us into assuming that companies are on the case—that we can, as I posited 20 years ago, have a positive impact on the environment without significantly compromising our way of life. It turned out to be a false hope: that we could shop our way to environmental health.

Clearly, we can’t. It’s time for a new green consumer to step into the breach, insisting that companies green up more than just their marketing claims.